Volume II

In the early eighteenth century, the word “gothic” was used derogatively to describe the darkness and horridness of the Middle Ages. In the European consciousness, “The Gothic [stood] for everything not: not modern, not enlightened, not free, not Protestant, not English” [1]. By the middle of the century, however, attitudes towards the gothic shifted, as the English developed a fascination with the frightening aspects of the gothic, including architecture. This period of medieval fascination, known as the Gothic Revival, saw a proliferation of gothic art, architecture and literature in England.

The revived Gothic style drew on the artistic concept of the sublime. In his 1757 A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful, the Irish philosopher Edmund Burke describes the sublime as anything in nature (such as rugged mountain landscapes or stormy weather) that causes the “passion” of “astonishment . . . [which] is that state of the soul, in which all its motions are suspended, with some degree of horror.” According to Burke, “objects of terror” greatly inspire this feeling of astonishment and “distress.” In describing sublime architecture, Burke writes that ruggedness, “greatness of dimension,” and “dark and gloomy” colors are all necessary qualities of sublime buildings. Darkness, Burke writes, “is known by experience to to have a greater effect on the passions than light.”

Philippe-Jacques de Loutherbourg. “A Philosopher in a Moonlit Churchyard.” 1790. [Public Domain] via Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection. http://collections.britishart.yale.edu/vufind/Record/1666679.

Samuel Hieronymus Grimm. “Blaise Castle.” 1788. © British Library Board (Additional MS 15540). http://www.bl.uk/onlinegallery/onlineex/topdrawings/b/005add000015540u00111000.html.

Another manifestation of the Gothic Revival was Gothic fiction. This formulaic literary genre describes damsels in distress imprisoned by violent villains in crumbling Gothic buildings. Gothic novelists riddle the interior of these buildings with secrets, such as “underground passages, dark labyrinthine corridors, trap doors, sliding panels concealing secret chambers, and dimly lit staircases” [2]. Gloomy forests and craggy mountains inevitably surround the scene, adding to the setting’s mysteriousness.

Ann Radcliffe, one of the eighteenth century’s most widely read Gothic novelists, helped create the Gothic villain, a character who threatens a young girl, usually a virgin, with various forms of violence. Through these characters, murder and the danger of masculine, physical violence emerge as Gothic motifs. Each of these recurring Gothic tropes combine to create a terrifying world, in which darkness and danger always lurk around the corner, especially for entrapped female characters.

Due to the violence, sexualization, and immorality in Gothic novels, they were considered lowbrow literature that could corrupt female readers. In Northanger Abbey, however, Catherine and Isabella, like many women of the time, refused to let the genre’s stigma prohibit them from reading Gothic novels. In fact, they take great pleasure in reading and discussing Gothic literature, such as Radcliffe’s The Mysteries of Udolpho. Once Isabella discovers Catherine’s affection for The Mysteries of Udolpho, she provides Catherine with a reading list of seven other novels. All of these novels are, according to Isabella, “horrid,” meaning they are dark and frightening.

Rev. William Warren Porter. “Scene from ‘The Mysteries of Udolpho.'” Undated. [Public Domain] via Yale Center for British Art, Gift of Edward Porter Street, Jr., Yale BE 1945W. http://collections.britishart.yale.edu/vufind/Record/3818683.

“After a very short search, you will discover a division in the tapestry so artfully constructed as to defy the minutest inspection, and on opening it, a door will immediately appear—which door being only secured by massy bars and a padlock, you will, after a few efforts, succeed in opening,—and, with your lamp on your hand, will pass through it into a small vaulted room.” [116, Northanger Abbey]

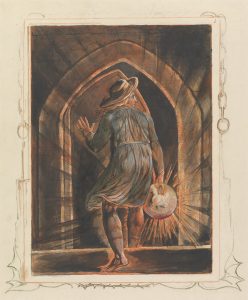

William Blake. “Jerusalem, Plate 1, Frontispiece.” 1804-1820. [Public Domain] via Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection. http://collections.britishart.yale.edu/vufind/Record/1667706.

“These apartments conducted them to a winding passage, that received light and air through narrow cavities, placed high in the wall; and was at length closed by a door barred with iron, which being with some difficulty opened, they entered a vaulted room.” [20, The Romance of the Forest]

At times, Austen seems to borrow entire passages from Radcliffe, mocking the formulaic nature of Gothic literature. Here, Austen imitates Radcliffe’s prose in the discovery of a hidden passage, barred doors, and vaulted rooms, creating a sense of mystery that is quintessentially Gothic.

“Catherine’s blood ran cold with the horrid suggestions which naturally sprang from these words. Could it be possible?—Could Henry’s father?—And yet how many were the examples to justify even the blackest suspicions!—And, when she saw him in the evening, while she worked with her friend, slowly pacing the drawing-room for an hour together in silent thoughtfulness, with downcast eyes and contracted brow, she felt secure from all possibility of wronging him. It was the air and attitude of a Montoni!” [137, Northanger Abbey]

Rev. William Warren Porter. “Castle of Udolpho.” Undated. [Public Domain] via Yale Center for British Art, Gift of Edward Porter Street, Jr. http://collections.britishart.yale.edu/vufind/Record/3818732.

When Montoni accuses Madam Montoni of poisoning his cup, Emily, Madam Montoni’s niece, comes to her defense. Montoni responds by locking the two women in a room:

“As he shut the door, Emily heard him turn the lock and take out the key; so that Madame Montoni and herself were now prisoners; and she saw that his designs became more and more terrible.” [296, The Mysteries of Udolpho]

In Northanger Abbey, Catherine references Montoni, the villain from The Mysteries of Udolpho who locks his wife and niece in a remote room of the castle, when she suspects that General Tilney committed a similar crime against his wife. Both Montoni and General Tilney embody the common Gothic tropes of domestic violence and paternal authoritarianism. In Northanger Abbey, Austen twists this trope to provide a critique of English society: while the General is a respected, English military man who didn’t ruthlessly torture and murder his wife in the end, he does turn out to be capable of other atrocities that Catherine doesn’t expect.

“As they drew near the end of their journey, her impatience for a sight of the abbey—for some time suspended by his conversation on subjects very different—returned in full force, and every bend in the road was expected with solemn awe to afford a glimpse of its massy walls of grey stone, rising amidst a grove of ancient oaks, with the last beams of the sun playing in beautiful splendour on its high gothic windows. But so low did the building stand, that she found herself passing through the great gates of the lodge into the very grounds of Northanger, without having discerned even an antique chimney.” [117, Northanger Abbey]

John Ruskin. “Mountain Landscape, Macugnaga.” 1845. [Public Domain] via Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection. http://collections.britishart.yale.edu/vufind/Record/1670656.

“He approached, and perceived the Gothic remains of an abbey: it stood on a kind of rude lawn, overshadowed by high and spreading trees, which seemed coeval with the building, and diffused a romantic gloom around. The greater part of the pile appeared to be sinking into ruins, and that, which had withstood the ravages of time, shewed the remaining features of the fabric more awful in decay. The lofty battlements, thickly enwreathed with ivy, were half demolished.” [17, The Romance of the Forest]

Here, Austen describes Catherine’s anticipation as the carriage approaches Northanger Abbey for the first time. Much to Catherine’s dismay, the abbey does not match the description of the abbey in Romance of the Forest. Radcliffe’s Gothic tropes are undercut here as Austen describes what Northanger Abbey is not: not surrounded by sweeping forests, and not adorned with Gothic elements.

Are the above passages pure satire or does Austen reveal some truth in Catherine’s fantasies about Northanger Abbey?

Politics and the Gothic in Austen’s England and Northanger Abbey

While these Gothic themes and fears might seem outlandish to modern readers, they metaphorically reflect political realities of the time. Witnessing the terrifying violence of the French Revolution, many English citizens feared that such violence could seep into England, and Gothic themes and literature emerged partially as a response to this concern.

Before the revolution, France was controlled by an absolute monarchy, but civil unrest led to the Storming of the Bastille on July 14, 1789, a violent event in which an armed crowd attacked a state prison (the Bastille) and freed the prisoners inside. A newspaper article from the July 20, 1789 issue of The London Times entitled “Rebellion and Civil War in France” describes some of the violence that occurred on July 14:

“On attacking the Bastile [the crowd] secured the Governor, the MARQUIS DE L’AUNEY, and the Commandant of the Garrison, whom they conducted to . . . the place of public execution, where they beheaded them, struck their heads on tent poles, and carried them in triumph to the Palais Royal, and through the streets of Paris . . . The Hotel de Ville, or Mansion-house, was the place that was next attacked . . . the Prevot de Marchand, or the Lord Mayor . . . was stabbed in several places, his head cut off, and carried away.”

In the midst of this overthrow of France’s absolute monarchy, a group of revolutionaries emerged as a new dominant political power. This new government enacted the Reign of Terror, a period between 1793 and 1794 when the revolutionaries publicly executed vast numbers of French nobles, elites, priests, and peasants who opposed the French Revolution. During this tumultuous period, there were 16,594 death sentences [1]. The revolution was not any easy, peaceful movement towards democracy, but an incredibly violent one.

Initially, the artistic and intellectual community in Britain supported the revolution [2]. For example, William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge saw the movement towards a more democratic society as a manifestation of the Romantic ideals of individualism and human potential. However, these literary figures, along with others, became disillusioned by the violent turn the revolution took with the Reign of Terror.

While the violence of the French Revolution terrified many English citizens, its democratic reform inspired an ambitious form of political radicalism in Britain. Public opposition to the corrupt, unreformed British political system had long been brewing, the royal family was unpopular, and many called for the people to be given more power than their constitutional monarchy allowed. With the French Revolution as an example, an under economic distress, some of the English working class sought to imitate the French. These citizens began forming radical political organizations, which worked towards parliamentary reform. Specifically, these radicals desired to move England in a more democratic direction by acquiring “universal” suffrage for all English men.

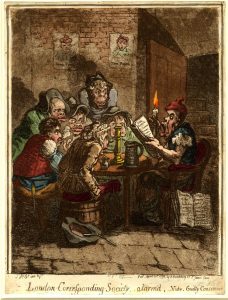

One such radical society was the London Corresponding Society, which was founded by a shoemaker, Thomas Hardy, in 1792. The English government grew increasingly paranoid of homegrown radicalism and potential uprisings, worrying that violent mobs would wreak havoc upon England. James Gillray’s print London Corresponding Society, Alarm’d reflects the way many people viewed British radicalism as a terrifying development in British politics. By depicting a London Corresponding Society meeting in the Gothic setting of an underground cellar, Gillray displays the London Corresponding Society as a group that secretly creates elaborate schemes to assassinate government officials. The faces of the individuals are exaggerated and monstrous.

James Gillray. “London Corresponding Society Alarm’d.” 1798. © The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license. http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/collection_object_details/collection_image_gallery.aspx?assetId=46811001&objectId=1478917&partId=1.

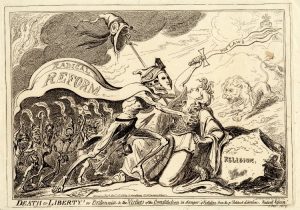

George Cruickshank takes this depiction of radicalism a step further in Death or Liberty, in which Death, disguised as liberty and radical reform, attacks Britannia, the female personification of England. While facing this dangerous radicalism, Britannia remains loyal to the British government, leaning on a rock with the word “religion” etched into it and raising a sword inscribed with “the laws.”

George Cruikshank. “Death or Liberty! Or Britannia & the virtues of the constitution in danger of violation from the grt political libertine, radical reform!” 1819. © The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license. http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/collection_object_details.aspx?objectId=1648397&partId=1.

While radicalism posed a terrifying threat to the status quo, the government these radicals wanted to reform also made life frightening for many English citizens, especially as political radicalism caused the British government to retaliate. For some, these repressive laws revealed the British government to be a patriarchal, authoritarian state that restricted personal freedoms.

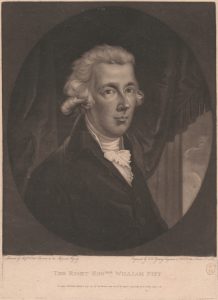

As Prime Minister starting in 1793, William Pitt the Younger became the figurehead for this repressive British Government, determined to put a stop to any radical sentiment in England.

John Young, after Anton Hickel. “The Right Honourable William Pitt.” 1797. [Public Domain] via Yale Center for British Art, Gift of Susan L. Darling in Memory of Arthur Burr Darling, Yale 1916. http://collections.britishart.yale.edu/vufind/Record/3660995.

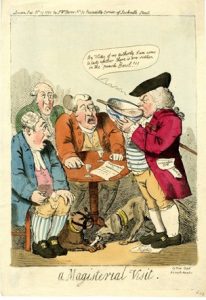

Pitt oversaw the passage of three significant acts (the Seditious Meetings Act, the Treasonable Practices Act, and the Suspension of the Habeas Corpus Act) as well as censorship of the press [3]. The Seditious Meetings Act was passed in December of 1795. It restricted the size of any gathering to fifty persons, and required a magistrate’s license to hold any gatherings in lecture and debate halls where policy was discussed. The following political cartoon satirizes the Seditious Meetings (or “Convention”) Act. It depicts three citizens seated at a small round table to drink punch, smoke, and discuss the news. They are interrupted by a Justice (right) who drinks from their punch-bowl, who says: “By Virtue of my Authority. I am come to taste whether there is any Sedition in the punch Bowl!!!” There are two papers in his pocket which read ‘Convention Bill’ and ‘Riot Act’.

Author unknown. “A magisterial visit.” Published by S.W. Fores. © The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license.

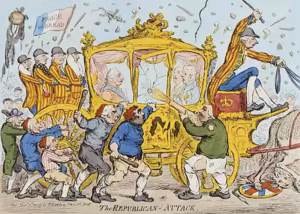

This act was accompanied by the Treasonable Practices Act, which made it a treasonable offense to “imagine, invent, devise or intend death or destruction, or any bodily harm tending to death or destruction, maim or wounding, imprisonment or restraint, of the person of…the King.” These acts were known as the “Gagging Acts” and were put into place after a mob attacked the carriage of King George III on his way to parliament in 1795 [4]. This stoning is depicted in the political cartoon below, which depicts the King sitting in his damaged coach while the mob attacks. Two terrified courtiers sit across from him. On the right we see William Pitt dressed as the coachman. He whips the horses, the hind legs of which are trampling Britannia. Her shield and spear are broken underneath her. Four footmen stand behind, all depicting various relevant political figures. The mob carries a French flag which reads “peace and bread.”

James Gillray. “The Republican Attack.” Published by Hannah Humphrey. © The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license.

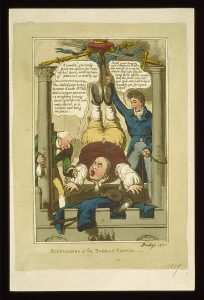

The Suspension of the Habeas Corpus Act, of which the full title was An act to empower his Majesty to secure and detain such persons as his Majesty shall suspect are conspiring against his person and government, was an eight-month suspension of a policy which allowed any prisoner or detainee to be brought before the court to decide if the person’s detention was justified according to law. The suspension of this act allowed the British government to crush any radical effort by arresting and detaining people as they pleased, possibly for dubious reasons, without repercussions. This suspension was widely viewed as a lack of accountability for the government, and a threat to British citizens’ civil liberties. The following satirical cartoon depicts the policy as a John Bull “suspended” by his ankles between two columns labeled “Lords” and “Commons.” John Bull says, “Lounds, get ready to cut me down for I am all but dead, and me time of penance is nearly up!” followed in the speech bubble below by the man in the green coat saying “The state of your bodily humours is such Mr. Bull, that a longer penance is necessary to bring down your pride and impudence, so be content and hang in peace.” The man in the blue coat says, “Hold your tongue you clamorous…rascal, it is my intention that you should hang there all the winter so that the frost may congeal your seditious blood & qualify you for a good subject.”

Suspension of the Habeas Corpus. England, 1817. [Feby] Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2004670123/. (Accessed July 17, 2017.)

One especially well-known occurrence of this type of spying is mentioned in Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s Biographia Literaria [6]. Coleridge and William Wordsworth were staying at an estate called Alfoxton in Somerset. Concerned citizens became convinced that the visitors were French spies, and reported their suspicions to the government. Subsequently, a government agent was sent out to investigate [7]. When it became clear that nothing was amiss, the agent went on his way. Coleridge says:

“…a spy was actually sent down from the government pour surveillance of myself and friend. There must have been not only abundance, but variety of these “honourable men” at the disposal of Ministers: for this proved a very honest fellow. After three weeks’ truly Indian perseverance in tracking us…he not only rejected Sir Dogberry’s request that he would try yet a little longer, but declared to him his belief, that both my friend and myself were as good subjects…Our talk ran most upon books, and we were perpetually desiring each other to look at this, and to listen to that; but he could not catch a word about politics.” [8]

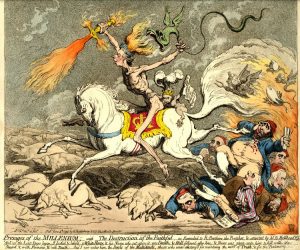

To some English citizens, William Pitt and the repressive government practices he represented were just as scary as the radicalism of the London Corresponding Society. In Presages of the Millenium, Gillray depicts Pitt in an explicitly Gothic manner. Riding on a military horse, Pitt is the figure of death itself, destroying everything in his path. In his left hand, he holds a fiery sword, in his right, a dragon-like monster. Such a depiction of Pitt reflects how the type of governmental authority he enacted could be terrifying and destructive.

James Gillray. “Presages of the Millenium.” 1795. © The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license. http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/collection_object_details.aspx?objectId=1478817&partId=1&searchText=Gillray+Presages&fromDate=1795&from=ad&toDate=1795&to=ad&page=1.

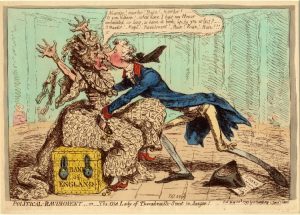

Similarly, in Gillray’s Political Ravishment, Pitt commits another destructive and horrifying act, in this case assaulting a female personification of the bank of England. While being attacked, the woman screams out “Murder! – murder! – Rape! – murder! – O you Villain! – what have I kept my Honor untainted so long, to have it broke up, by you at last ? – O murder! – Rape! – Ravishment! – Ruin! – Ruin! – Ruin!!!” In this terrifying scene, Pitt’s political power is depicted through sexual domination. His authority, presence, and actions are similar to those of gothic villains.

James Gillray. “Political-ravishment, or the old lady of Threadneedle-street in danger!” 1797. © The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license. http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/collection_object_details.aspx?objectId=1478863&partId=1&searchText=gillray+political+ravishment&page=1.

Austen wrote Northanger Abbey during this politically tumultuous time, when frightening figures, including political radicals on one side and William Pitt’s network of spies on the other, established an atmosphere of fear, danger, paranoia, and suspicion: the typical setting for a Gothic novel [9]. Catherine herself sees the Gothic in her experiences at Northanger Abbey, suspecting General Tilney of imprisoning or even murdering his late wife. Her wild imagination is left unchecked until Henry returns at the end of chapter 24 and finds Catherine snooping in his mother’s room, searching for answers to the mystery she has imagined. He reprimands her sharply:

“Dear Miss Morland, consider the dreadful nature of the suspicions you have entertained. What have you been judging from? Remember the country and the age in which we live. Remember that we are English, that we are Christians. Consult your own understanding, your own sense of the probable, your own observation of what is passing around you. Does our education prepare us for such atrocities? Do our laws connive at them? Could they be perpetrated without being known, in a country like this, where social and literary intercourse is on such a footing, where every man is surrounded by a neighbourhood of voluntary spies, and where roads and newspapers lay everything open? Dearest Miss Morland, what ideas have you been admitting?”

This fear and tension recurs throughout Northanger Abbey. On page 138 of the novel, Austen may be hinting at the government’s practices of repression and censorship when the General tells Catherine:

“I have many pamphlets to finish’, said he to Catherine, ‘before I can close my eyes; and perhaps may be poring over the affairs of the nation for hours after you are asleep.”

Some Austen scholars [10] have concluded that General Tilney was one of the voluntary spies that Henry mentioned in his reprimand of Catherine. Voluntary spies often found and reported “seditious” or radical writing, and General Tilney’s “poring over the affairs of the nation” in this passage may mark him as an inquisitor, reading publications for sedition and reporting suspicious findings to the Home Office.

In many ways, Catherine’s role as a pawn between the conflicting forces of father and son at the end of the novel resembles Britannia, the female personification of England, often portrayed as loyal to the authority of the government. Thomas Rowlandson expounds on Britannia’s virtues in The Contrast, showing that she represents “religion, morality, loyalty, obedience to the laws, independence, personal security, inheritance, protection of property, industry, national prosperity, happiness.”

Thomas Rowlandson. “The Contrast.” 1793. © The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license. http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/collection_object_details.aspx?objectId=1478887&partId=1&people=109191&peoA=109191-2-23&page=1.

The themes of paranoia, fear, and suspicious activity were likely at least partially responsible for the Gothic novel craze that Austen satirizes in Northanger Abbey. Even as she makes fun of the horror genre of the time, the political context that partially inspired these novels is subtly present throughout Northanger Abbey.