Background

Northanger Abbey follows the story of Catherine Morland, a young English country girl, on her travels to Bath and the titular Northanger Abbey. The satirical storyline emerges early in the novel, even in the opening line of “No one who had ever seen Catherine Morland in her infancy, would have supposed her born to be an heroine” [5]. In order to provide brief contextual information on the novel, we have created a general overview of important topics that includes a biography of Austen, a reception history of Northanger Abbey, a brief guide for how to read Austen, a description of the literary trends during Austen’s lifetime, and a timeline of historical events relevant to Northanger Abbey. Each section includes embedded discussion questions that relate this information back to the novel. If you want to read more about these topics, you can click on the hyperlinked words in blue.

Jane Austen and Northanger Abbey: A Brief Biography

Jane Austen was born on December 16, 1775, in Steventon, Hampshire, England. Her parents, Cassandra and George, were prominent middle-class members of their community. Her father attended Oxford, and served as a clergy member for an Anglican parish. The Austen family was very close-knit, and the children’s creativity was nurtured. Austen and her brothers and sisters were encouraged to read their father’s extensive collection of books. They also wrote and performed their own plays. Austen shared especially close bonds with her father and her older sister, Cassandra. Austen and Cassandra were sent to boarding schools in pursuit of further education during Austen’s early adolescent years. This education proved short, however, as the Austen family could no longer afford boarding school. From this time forward, they lived with their family at home and pursued more informal methods of education.[1]

Hampshire, England. Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

According to Cassandra, Jane Austen wrote what was to become Northanger Abbey while she was in her twenties, around 1798 or 1799. She originally titled the novel Susan. After failing to publish two other novels, Austen’s hopes were renewed when her elder brother, Henry, was able to sell Susan to a publishing house called Crosby & Co. The publisher planned to send the book to print in a timely manner, and even advertised it in a local brochure. However, the book lingered unpublished at Crosby & Co. for six years before Austen finally reached a point of frustration. In 1809 she wrote a firm letter to Richard Crosby under the pseudonym of “Mrs. Ashton Dennis” which, when read as an acronym, notably spells out “MAD.”[2]

She inquired as to why the book had never been published, since “early publication was stipulated for at the time of sale” then offered to send another copy of the manuscript if they had lost theirs. She went on to state that if they did not respond promptly, she would take the liberty of pursuing publication via another publisher. An equally firm response was returned. Mr. Crosby wrote back that “there was not any time stipulated for its publication, neither are we bound to publish it” and threatened to take legal action if Austen attempted to publish her book anywhere else. However, he did also offer to sell the manuscript back for the same amount he had bought it for. Austen could not afford to buy the novel back. Thus, it collected dust on the shelves of Crosby & Co. for the following seven years. In 1816, Austen’s brother Henry bought Susan back for the same ten pounds it had fetched.

He followed the repurchase by revealing to the publisher that the book was written by the author of the now successful Pride and Prejudice and Sense and Sensibility. In the midst of this turmoil, another novel titled Susan was published. Thus, as Austen revised her book, she changed the titular character’s name to Catherine. She then wrote an “advertisement by the authoress” intended to explain why certain parts of the book were not as current as they were at its time of composition. The note read as follows:

“ADVERTISEMENT BY THE AUTHORESS, TO NORTHANGER ABBEY. This little work was finished in the year 1803, and intended for immediate publication. It was disposed of to a bookseller, it was even advertised, and why the business proceeded no farther, the author has never been able to learn. That any bookseller should think it worthwhile to purchase what he did not think it worthwhile to publish seems extraordinary. But with this, neither the author nor the public have any other concern than, as some observation is necessary upon those parts of the work which thirteen years have made comparatively obsolete. The public are entreated to bear in mind that thirteen years have passed since it was finished, many more since it was begun, and that during that period, places, manners, books, and opinions have undergone considerable changes.”

Soon after writing this, in another surprising turn of events, Austen resolved to further delay publication. As she wrote in a letter to her niece Fanny in early 1817, “Miss Catherine is put upon the shelves for the present, and I do not know that she will ever come out.” Tragically, she passed away before her Miss Catherine had the chance to debut. After her death, her brother Henry renamed the novel Northanger Abbey, took it to publisher John Murray, and released it alongside Persuasion in December, 1817.

By Jane Austen (1775 – 1817) (Lilly Library, Indiana University) [Public domain or Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Henry also added a “biographical notice” to the beginning of the book, detailing aspects of Jane Austen’s life. The notice is similar in tone to a eulogy. It describes her character through the eyes of her brother, and also quotes several of the author’s own letters. The biography paints an idyllic picture of a cheerful, placid, “faultless” author and a “genius” who was modest about her talents. It portrays her life as uneventful, peaceful, quiet, and almost too good to be true. [3] It was the first attempt to provide a basic biography of Austen’s life using her true name, and thus carried much weight to sway the public’s opinion of her. This biography sowed the seeds of the still perpetuated myth of Austen as a demure and shy woman, holed up in isolation in the English countryside, writing only during her spare time. Biographies like the one by Henry Austen have blotted from history a vision of Austen as possessing a fiery spirit and a lively imagination, and of her books as written with much more than a tiny village in mind.

In fact, her world was much bigger than just tiny English villages. Austen had two brothers, Francis and Charles, who were sailors in the British Navy. They had the opportunity to travel the world and bring their stories back home to Austen, who was greatly inspired by them. According to Edward Austen-Leigh in his Memoir, Austen “felt herself at home with ships and sailors” and possessed a “partiality for the Navy” about which she wrote with “readiness and accuracy.” Further global perspective came from her cousin Eliza Hancock, who was fourteen years her senior. Born in Calcutta, India, Eliza was surrounded by adventure, intrigue and gossip. She was most likely the daughter of George Austen’s sister Philadelphia and Tysoe Hancock, but was rumored to be the natural child of her godfather Warren Hastings. Hastings would later become the first Governor-General of Bengal, India. In 1765, Eliza moved to England with her parents, later settling in France. It was there that she met and married Jean-François Capot de Feuillide, a captain of the French army. However, she was forced to leave France and settle again in England after the beginning of the French Revolution. Jean-François Capot de Feuillide, Eliza’s husband, was arrested for loyalty to the French monarchy and guillotined. In 1794, Eliza arrived to Steventon at a critical moment in Austen’s life, during her pre-adolescent years. Austen’s worldview was shaped by her cousin and her ties to India. According to Austen’s nephew James Edward Austen-Leigh, Eliza had a “significant influence on her teenage years” and was one of her “most colorful connections.” Eliza was a notorious flirt, skilled socialite, and reportedly possessed great beauty and talent in many areas. [4]

Portrait of Eliza de Feuillide, By Unidentified painter, 18th-century portrait painting with Unidentified or Unknown, artist, location and year. (Own work) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

In 1869, nephew James Edward Austen-Leigh published a biography of his aunt entitled A Memoir of Jane Austen. It was a product of collaboration between many of Austen’s family members, and drew heavily upon their recollections of her. The family encountered some disagreement over how much personal information should be revealed in the memoir, such as Austen’s romantic life. Austen-Leigh referred to “dear Aunt Jane”[5] as someone who was very centered upon domestic life and uninterested in public renown for her writing. He portrayed writing as a hobby for her, something she only did in moments of free time. In 1871, a second edition of the memoir was published, this time including primary writings from Austen herself that had previously gone unpublished. Because her sister Cassandra had made the decision to burn most of these letters, the memoir was able to draw from a precious few of them. However, these manuscripts do serve to inform us that Jane Austen was in fact interested in writing as much more than a simple hobby, and may have been less placid and demure than her nephew initially described her.

James Edward Austen-Leigh

See page for author [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

The portrayal of Austen as reserved in the writings of both her brother and her nephew may simply be a product of Victorian conventions of biography. Consistent with such tradition, these biographies kept most sensitive information out of the public eye. [6] The memoir in particular was important, however, as it threw Austen’s works further into the literary spotlight, and rendered her books visible and accessible to a wider audience. It is likely that if not for James Edward Austen-Leigh and his memoir, Austen’s novels would not be as widely circulated as they are today.

What aspects of Jane Austen’s childhood and young-adulthood do you think influenced her writing the most? Why? (For instance, how do you think her exposure to her father’s vast library influenced her message about the role of the novel?)

What are the risks of interpreting the text through this biographical material?

What aspects of Northanger Abbey do you think demonstrate Austen’s global perspective?

Marilyn Butler argues that Austen was not a feminist, while Margaret Kirkham suggests otherwise. Based on your reading of Northanger Abbey, which do you agree with and why?

Reading Austen

Reading Jane Austen requires patient, engaged reading because her work is almost always ambiguous. This complexity can make it difficult to pin down Austen’s use of satire in Northanger Abbey, especially for modern readers. While this novel is often read as a satire of the popular gothic novels of the time, it is hard to know when Austen satirizes the gothic genre and when she embraces it. Northanger Abbey offers conflicting perspectives on Austen stance on Regency England’s culture and politics, including gender relations, fashion, and government. Consider the description of Mrs. Allen in chapter 2:

“Mrs. Allen was one of that numerous class of females, whose society can raise no other emotion than surprise at there being any men in the world who could like them well enough to marry them. She had neither beauty, genius, accomplishment, nor manner. The air of a gentlewoman, a great deal of quiet, inactive good temper, and a trifling turn of mind were all that could account for her being the choice of a sensible, intelligent man like Mr. Allen. In one respect she was admirably fitted to introduce a young lady into public, being as fond of going everywhere and seeing everything herself as any young lady could be. Dress was her passion. She had a most harmless delight in being fine; and our heroine’s entree into life could not take place till after three or four days had been spent in learning what was mostly worn, and her chaperone was provided with a dress of the newest fashion. Catherine too made some purchases herself, and when all these matters were arranged, the important evening came which was to usher her into the Upper Rooms. Her hair was cut and dressed by the best hand, her clothes put on with care, and both Mrs. Allen and her maid declared she looked quite as she should do. With such encouragement, Catherine hoped at least to pass uncensured through the crowd. As for admiration, it was always very welcome when it came, but she did not depend on it.” [10-11]

In this passage, Austen’s stance on fashion is ambiguous, especially in a term like “harmless,” which could be read satirically or not. How does Austen satirize, praise, or merely describe female codes of dress here? Does she do all these things simultaneously? If so, how?

Because of Austen’s ambiguity, a good reader takes various interpretations into account. Many people have and do read Austen’s novels as conservative reaffirmations of Regency England’s gender and political hierarchies. However, some scholars, like Claudia Johnson, have argued that Austen uses the idea of the English family as a metaphor to critique patriarchal government authority. Given that Jane Austen can be read in these opposing ways, we want to consider both as feasible interpretations.

18th & 19th Century Literary Scene

Broadly, Romanticism was the dominant literary and artistic movement during Jane Austen’s career. As a movement, Romanticism revolutionized literary form, content, and theories of literature, art, and beauty in the late eighteenth century and first half of the nineteenth century. The two figures credited with beginning this movement are William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge.

William Say, after James Northcote. “S.T. Coleridge Esq.” Undated. [Public Domain], via Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection. http://collections.britishart.yale.edu/vufind/Record/3651231.

James Bromley, after Sir William Boxall. “William Wordsworth.” 1832. [Public domain], via Yale Center for British Art, Yale University Art Gallery Collection. http://collections.britishart.yale.edu/vufind/Record/3894594.

The 1798 release of their collaborative book of poetry, Lyrical Ballads, ushered in a new literary era. Wordsworth’s Preface to Lyrical Ballads was the artistic manifesto of Romanticism. In the Preface, Wordsworth embraces poetry of ordinary events as the most valuable literary form, and draws attention to the natural world, individualism, and the vast capabilities of the human mind, specifically imagination, consciousness, and memory. With this strong focus on realism and poetry, he dissolves the credibility and value of the novel, which authors such as Daniel Defoe, Samuel Richardson, and Henry Fielding popularized earlier in the eighteenth century. Many intellectuals and artists began thinking of the novel as a genre based on overblown romantic fantasies that would corrupt readers into believing fiction.

Despite this highbrow opposition to the novel, many women, such as Frances Burney, Mary Wollstonecraft, Maria Edgeworth, Ann Radcliffe, and Jane Austen, succeeded in writing and publishing popular novels during the last decades of the eighteenth century and the first few decades of the nineteenth century. Radcliffe helped establish the gothic novel, a genre obsessed with medieval themes and architecture, including dark castles and abbeys. The plots of these gothic novels were highly supernatural, with horrifying stories set in these old and mysterious buildings. The fear that the Reign of Terror sparked in England pushed many gothic authors to set their stories in continental Europe, portraying countries like France, Italy, and Switzerland as dangerous and violent places.

William Bond. “The Mysteries of Udolpho.” 1796. © The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license. http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/collection_object_details.aspx?objectId=3102569&partId=1&people=131776&peoA=131776-2-70&page=1.

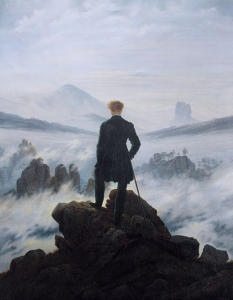

Even though the Romantics opposed the genre of the popular gothic novel, they were heavily influenced by gothic themes. For example, in 1798 Samuel Taylor Coleridge helped create gothic Romanticism with his poem “Rime of the Ancient Mariner,” and Mary Shelley published her gothic Romantic novel Frankenstein in 1818. Although Frankenstein is a novel, Mary Shelley is different from the other female novelists previously mentioned because her marriage to poet Percy Shelley gave her direct connections to the Romantic movement. Though working within the genre of the novel, her work still follows the Romantics’ literary ideals. In particular, Romantic authors were drawn to the gothic idea of the sublime, a concept originally explained by philosopher Edmund Burke in 1857 and later taken up by gothic novelists and Romantics as a way to explain the scary and astonishing grandeur of the world. The 1818 painting Wanderer above the Sea of Fog by David Friedrich (below) offers a visual example of the sublime, presenting a natural landscape that is both magnificent and terrifying at the same time. While Romantics mainly focused on the sublime in nature, many gothic authors used this technique to describe both the natural world and architecture, such as the gloomy forests and vast abbeys in their stories.

Caspar David Friedrich. “Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog.” 1818. [Public domain] via the Athenaeum. https://www.the-athenaeum.org/art/detail.php?ID=58460.

Begun in 1798, Jane Austen wrote Northanger Abbey in the heyday of Romantic poetry and gothic novels. In fact, Austen references and alludes to several of Ann Radcliffe’s novels in Northanger Abbey, including The Romance of the Forest, published in 1791, and The Mysteries of Udolpho, published in 1794.

Austen also alludes to the concepts of Romanticism. Specifically, the beginning of Northanger Abbey, with the “defense of the novel” at the end of chapter 5, suggests that Austen wrote against the artistic inclinations of her Romantic contemporaries. While Wordsworth makes it clear in his preface that he believes poetry “binds together by passion and knowledge the vast empire of human society,” Austen states that the novel is the genre which has “afforded more extensive and unaffected pleasure than . . . any other literary corporation in the world” [23]. How does Austen defend the novel in this passage? Is pleasure the goal of reading, for Austen? How do we reconcile Austen’s defense of the novel with the fact that she is writing a satire of a novel? Do you think Austen might be praising certain kinds of novels while satirizing others? How does she define a good novel, or good literature?

Even though Austen pushes against the Romantics’ critique of the novel, Northanger Abbey as a whole demonstrates the various ways Austen uses ideas central to both Romanticism and gothic novels, such as the sublime and abbey architecture. However, in borrowing these ideas, she refashions them. By setting this novel in England, for example, Austen may be expressing the gothic nature of English society. Recognizing Austen’s connections with the literary movements of her time allows us to see not only how she engaged with other writers, but also how she engaged with larger political and historical contexts.

Historical Context for the Novel

Where do you see the following events playing out in the novel? Mark passages as you read.

1600: Formation of the East India Company

Thomas Malton the Younger. “East India House.” Undated. [Public Domain] via Yale Center for British art, Paul Mellon Collection. http://collections.britishart.yale.edu/vufind/Record/3631995.

1760: King George III comes to power, serving from 1760-1820

John Nost III. “George III.” 1764. [Public Domain] via Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection. http://collections.britishart.yale.edu/vufind/Record/1666360.

1783: Prime Minister William Pitt comes to power, serving from 1783-1801 and 1804-1806

Studio of Thomas Gainsborough RA. “William Pitt.” 1787 to 1789. [Public Domain] via Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection. http://collections.britishart.yale.edu/vufind/Record/1670979.

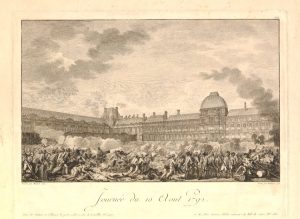

1789: French Revolution begins, continuing through 1799

Isidor Stanislas Helman, after Charles Monnet. “Les principales journées de la Révolution/Journée du 10 Aout 1792.” 1793. © The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license. http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/collection_object_details.aspx?objectId=1536691&partId=1&searchText=French+Revolution&page=1.

On July 14th, 1789, the Storming of the Bastille signaled the start of the French Revolution. Rioters stormed the Bastille fortress for weapons and gunpowder, wreaking havoc in Paris. A few years later, on September 21st, 1792, the monarchy was successfully overthrown, and its leaders publicly executed.

Shortly after this horrific event, the Reign of Terror began, lasting from September 5th, 1793 until July 27th, 1794. During the Reign of Terror, aristocrats and clergy were executed, while British support for the revolution declined sharply amidst fears of French invasion and homegrown riots in Britain. The violence contributed to the rise of Gothic literature in England, often set in continental Europe.

On November 9th, 1799, Napoleon Bonaparte came to near-absolute power as France’s First Consul, ending the French Revolution.

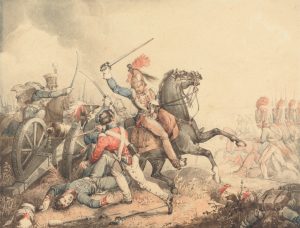

1803-1815: Napoleonic Wars

William Heath. “An Episode at the Battle of Waterloo.” 1817. [Public Domain] via Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection. http://collections.britishart.yale.edu/vufind/Record/3647983.