Nikko is a small but culturally rich town, located about a two-hour train ride southwest of our home at ARI. Possessing the extremely unique status as an UNESCO World Heritage Site, Nikko is a wonderful place to explore historical Japanese culture, and, in our case, examine how that culture is deeply embedded in the nature surrounding the area.

Most notable are the numerous stories and folk tales surrounding the mountains and hills in which Nikko is nestled. The earth itself is revered in Nikko, mountains and trees embodying spirits of man, woman, and the divine.

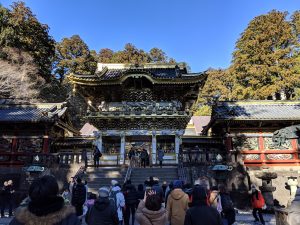

It perhaps makes sense, then, that some of the most ornate and beautiful temples and shrines (like the above gate) in all of Japan reside in Nikko, and Japanese royalty have been making pilgrimages there to worship and celebrate for centuries. Japan’s longest-ruling emperor is (maybe) buried there as well, granting the area even greater significance.

However, despite the sprawling Buddhist and Shinto temples and shrines, there is a decided reverence for nature and the environment deeply evident in the spaces. It’s decidedly difficult to ignore the massive, ancient trees surrounding all parts of the temples and shrines we visited in Nikko, branches brushing the roofs of temples and gates in some places. As much as possible, nature has been preserved in all of her glory in Nikko, especially around the shrines and temples. To do any harm to nature beyond what was necessary to construct the temples would, of course, have caused great harm to the already incredible spiritual value of the place.

Even the architecture itself, especially this bridge outside of the World Heritage Site, is sacred. The crimson bridge above was said to have been created when a Japanese emperor visiting the site asked the gods for a way to cross the river — his prayer was answered by two snakes, who came from the hills to join together and form a bridge. Now protected from foot traffic, the bridge stands as a monument to the spiritual significance that nature still holds in Nikko.

Even inside the gates to shrines, the trees join with the shrine buildings in a quiet solidarity, equally as sacred as the buildings near to them. Nature is meant to be a great part of the experience of visiting Nikko’s temples and shrines, the monumental trees supporting the shrines in their reverie in nature.

These trees are deep within the Toshogu shrine proper, standing around the beautifully-cut stone staircase up to the Inner Shrine and the emperor’s gravesite. The staircase is beautiful in its simplicity, allowing its visitors to take full appreciation of the surrounding ancient forest. Most of the trees are seven or eight hundred years old, protected by the reverence people hold for them. The significance of this is enormous, especially considering that Japan is always in need of lumber for building. To protect these trees, which would no doubt be worth a fortune to a logging firm, stand tall in the face of industrial logging and development.

Taking the reverence of nature in mind, it’s no coninceidence than that Toshogu’s most sacred areas, the Inner Shrine and the emperor’s grave, lie at the top of one of Nikko’s several peaks, the farthest possible inside nature. To be so surrounded by the imposing trees, visiting a grave dedicated to Japan’s longest ruling emperor, is truly a unique experience. The coexistence between nature and religion is something that is rarely seen in the other areas of Japan that we’ve visited, and is unlike anything I’ve experienced before.

Bennett R.

Recent Comments