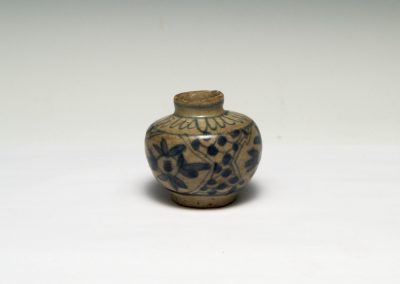

Ceramics

Each of these miniature vases were made during the Qing Dynasty in China. This dynasty lasted from 1636-1912, however, St. Olaf’s collection contains pieces from the latter half of the Qing Dynasty rule, from 1723-1850. Miniature vases such as these were not very common at this time. They did not serve as functional objects, instead, they were most likely collected for their aesthetic appeal. The collector must have focused on the varying vase shapes, designs, and glaze colors of miniature ceramics and desired to showcase a large sample of miniature vases. These vases would have been stored in curio cabinets. Curio cabinets were intricately carved wooden boxes made for housing beautiful, miniature objects, or to be filled with practical cosmetic items and used as an “overnight bag” for traditional literati scholars. Each object would have had its own drawer, and in more expensive cabinets, each drawer was custom-made to fit the item that it would hold.

If you would like to listen rather than read, please click below.