The St. Olaf Rock

Jeff M. Sauve

Nearly a century ago, Georgina Rostad ex-’19 posed for a picture standing next to the St. Olaf Rock. From Rostad’s time to the present, countless others have similarly been photographed in front of, on top of and next to the rock, which has the college emblem chiseled on its side. The imposing granite boulder, however silent, has played a small part in Manitou Heights’ history.

Originally the rock was located on the brow of Norway Valley behind Old Mohn Hall, and only a portion of it was exposed above ground. N. Edward Mohn, class of 1899, the eldest son of then President Thorbjorn N. Mohn, took it upon himself in the summer of 1897 to carve what is believed to be the first representation of the college seal.

His younger brother Ted recounted in the Mohn Family Tapestry (1964) that Edward used a single chisel that soon became “blunted and needed to be sharpened. After sharpening, it should have been tempered, but Edward had no means of tempering steel. Before he finished, the cutting edge of the chisel became as soft as malleable iron. For this reason the seal was not cut as deeply as Ed would have liked.”

When excavations began in 1967 for the newly-built Science Center, the St. Olaf Rock was unearthed. It was moved to its present location in 1968 for a more readily public view (in front of Tomson Hall). Few people could have guessed the enormity of the boulder scooped out of the ground. One student said it was certainly the largest paperweight found on campus.

The rock’s expansive and exposed surface offered mischievous students a generous palette. Apparently in the short window from 1968 until the plaque’s dedication in September 1969, pranksters painted red, black and multicolored polka dots on the rock, making it look like a giant Easter egg. In April 1972, someone armed with a can of red spray paint and strong anti-Vietnam emotion misspelled “Strike” on the rock’s face, instead proclaiming “Srike” for peace.

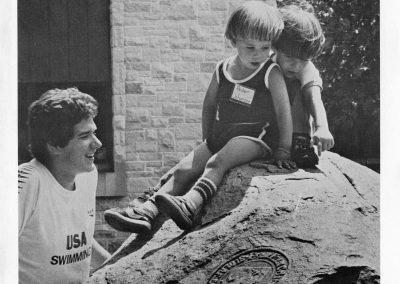

Since 1972, the rock has received many visitors and no apparent vandalism. Those who stop for a few moments read the plaque and take a photo or two. It’s not uncommon to witness children climbing happily to the top, enjoying history from a much different perspective.

Bailey the Future Ole

It’s not uncommon to witness children climbing happily to the top, enjoying history from a much different perspective.

The Campus Iceberg

Georgina Rostad, ex-’19, posed for a picture standing next to the St. Olaf Rock. Originally the rock was located on the brow of Norway Valley behind Old Mohn Hall, and only a portion of it was exposed above ground.

Current View: St. Olaf Rock

In nice weather, students can be found reading or hanging out with friends at the rock.

Fram! Fram!

N. Edward Mohn, class of 1899, the eldest son of then President Thorbjorn N. Mohn, took it upon himself in the summer of 1897 to carve what is believed to be the first representation of the college seal.

Spelling Always Counts!

In April 1972, someone armed with a can of red spray paint and strong anti-Vietnam emotion misspelled “Strike” on the rock’s face, instead proclaiming “Srike” for peace.

Recent Comments