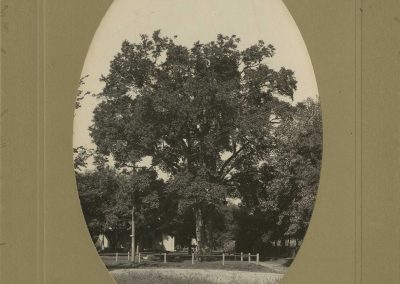

The St. Olaf Elm

Emily Hoar

Until its removal in 1921, the St. Olaf Elm stood for decades at the jog where West Third Street and Forest Avenue meet. Although long-gone, in its heyday, the elm was considered one of Northfield’s most beloved trees, according to local author Harvey E. Stork.

In his book The Trees of Northfield (1948), Stork wrote: “About 1894 or 1895, it was slated to be cut down, but some tree lovers came to its rescue and it was granted another 25 years of life. In order to assure its future, [St. Olaf] Professor [Andrew] Fossum, [whose residence was near the tree], prevailed on the city council to set aside the little triangle on which the tree stood as a city park.” Stork added, “With his victory, the smallest city park in the country was born.”

Fossum organized a benefit baseball game on June 14, 1897, between Carleton and St. Olaf to raise money to build an iron fence around the elm “to keep teams, cattle etc., from trespassing thereon.” By that fall, the city council also enacted an ordinance that provided “punishment by fine or imprisonment for any person who shall willfully cut, injure, or deface the said St. Olaf Elm.” The ordinance was spelled out on a large board and nailed to the tree as a public reminder.

After 1897, many people, including students from both colleges, enjoyed stopping by the tree. Edel Ytterboe Ayers ’20 recalled in her book The Old Main (1969), “I remember seeing the Carleton College girls taking a walk … up to the St. Olaf Elm on Forest Avenue. They marched two by two with a chaperone marching ahead and another chaperone following behind. Those were strict days indeed, but no one seemed to object.”

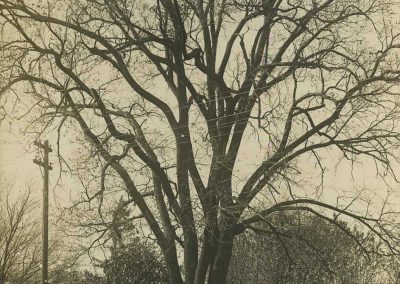

Despite its protections, the tree was not shielded from the elements, and it deteriorated. For instance, in March 1900, a lecture was held (featuring a novel early projection system—a “stereopticon”), with all admission fees donated toward repairing the elm. In 1905, two metal rods were installed to provide strength and brace a split between the two largest branches.

By 1920, most of its largest branches were dead, the trunk was rotting, the iron railing had failed, and the small “park” surrounding it had succumbed to weeds. Indeed, an anonymous opinion piece in the Northfield News declared it “an eye-sore. … If the tree does fall during a mighty blast, it will strike any one of three residences near. … [It] has long since been a chief hangout place of an undesirable type of lovers.” Even so, many residents pleaded that they “could not get along without it.”

Unfortunately, it was deemed a safety hazard. On August 3, 1920, the council ordered it cut down. The tree was finally removed in January 1921, after three weeks of cutting due to its immense size.

Smallest Park in America

Until its removal in 1921, the St. Olaf Elm stood for decades at the jog where West Third Street and Forest Avenue meet. Although long-gone, in its heyday, the elm was considered one of Northfield’s most beloved trees. Creator Ole G. Felland

Looking for Trouble

The Northfield City Council also enacted an ordinance that provided ìpunishment by fine or imprisonment for any person who shall willfully cut, injure, or deface the said St. Olaf Elm.î The ordinance was spelled out on a large board and nailed to the tree as a public reminder. Creator Edward Michaelson

Front Page News

A benefit baseball game on June 14, 1897, between Carleton and St. Olaf to raise money to build an iron fence around the elm “to keep teams, cattle etc., from trespassing thereon.” Creator Northfield News, June 12, 1897

All Fenced In!

St. Olaf Professor Andrew Fossum, whose residence was near the tree, prevailed on the Northfield City Council to set aside the little triangle on which the tree stood as a city park. Local author Harvey E. Stork wrote in his book The Trees of Northfield (1948), “With his victory, the smallest city park in the country was born.”

Recent Comments