Well-Worn Footpath

Jeff M. Sauve

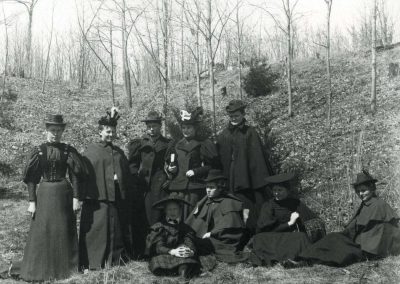

What do golf balls, bullet casings, baby food jars, and a 1902 silver half dollar all have in common? Each item was found by someone poking around in Norway Valley. Since the early 1880s, students have made the woods their playground, and faculty have found in them an opportunity for classroom research and field study.

The current trailhead starts near the fire hydrant behind Regents Hall. The winding half-mile path, under a forest canopy, provides a brief respite in the natural world. Spring wildflowers such as jack-in-the-pulpit, wild ginger, and bloodroot dot the landscape. In the frigid winter, snow crunches underfoot while observers spot tracks from deer, turkey and rabbit.

The three-foot-wide path attests to many hikers over the years. Looking more closely at the trees, hikers will find carved initials such as “JAW” or fading chiseled arrows directing cross-country runners. Up in the trees are embedded red metal triangles that occasionally provide yet another directional clue. Remnant forts and art projects are scattered about, too.

The main trail was not developed until October 1935, when federal aid workers cleared the paths and paved them with cinders. Interestingly, the Blue Key Society had proposed the previous spring to develop a five-mile trail system from Norway Valley to Pop Hill behind Thorson Hall and Heath Creek across Highway 19. The primary purpose of the trail, according to the student newspaper, the Manitou Messenger, was “the facilitation of campus bird study, includes, in its itinerary, such spots as the ‘Lover’s Leap’ rock, the Delta Chi Retreat, and Pop’s Cave, and many other haunts of our feathered friends.”

In the mid-1970s, President Sidney Rand created a special task force that addressed what the college should be doing to preserve the valley and its various natural endowments.

Recommendations included placing wood chips or other materials on the path, installing metal signs for plant identification, and adding the occasional bench. Professor Harold Hansen ’38 created wooden signs for trail identification (the signs have long since disappeared), and landscaping was undertaken to alleviate erosion on the hillside paths; unfortunately, the benches never materialized.

Professor Hansen, who often brought students in his plant morphology class to Norway Valley, once told them as they reached the end of the trail, near the Ole O. Fugleskjel monument [see site story, “Monument in the Woods”], “It’s okay to preserve the memories of people by erecting monuments. But the way you treat the valley will be the real monument to the pioneer spirit. Then you can show your grandchild something that’s still like it was those many years ago.”

Taking a Hike.

Rebecca Rand ’10 and Former College Pastor W. Bruce Benson Check Out the Spring Flora.

Recent Comments