Display of the Warrior:

The portrayal of samurai in woodblock printing

Sitting astride his horse the warrior glances down at the wounds he’s sustained. He was sure they would kill him, but as day slowly fades into night he has found himself alive and alone with only his thoughts and his swords. The full moon casts a perfect shadow on a pond, as he stoops down for a drink, finally filling with his mouth with more than blood and bile. His eyes well up as cherry blossoms blow like pink snow around him. As he soaks in the atmosphere we can’t help but wish he was sitting here with his calligraphy set instead of his armor. He sighs deeply, knowing what he must do. He thinks of the enemies he’s killed, his sword had been strong and swift, but it was not enough. Drawing the family heirloom one final time, he pauses to admire the scenery once more, and then draws his sword across his body. His organs fall into his hands and as he stifles a scream. He slumps backwards like a wounded crane returning to his beginnings.

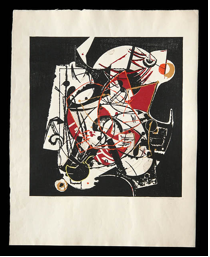

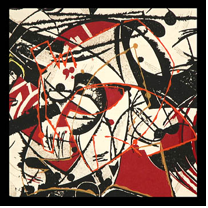

This is my own heavily idealized image of the Japanese warrior. This image has been cultivated through video games, books, anime, movies and of course Japanese art. In Yoshida Hodaka’s “Profile of an Ancient Warrior” he creates an image of a different kind of warrior as he reaches back in time. “Profile of an Ancient Warrior” is during his “primitive energy” phase, which is this artist’s effort in “evoking a feeling of the energy in primitive life,” according to Eugene Skibbe. Yoshida is seeking to tap into a primordial current that flows through all people, a flow which he found in Native American and the per-Columbian ruins of Mexico. He does this with his palette choice of charcoal black and either blood or berry red. Despite the attempt to find common roots, the warrior in this painting is distinctly Japanese. I am not sure if this was intentional or if Yoshida’s socialization got the better of his artistry and vision. Either way, this painting is steeped in his inherited symbolism, on display are the quintessential samurai symbols: the topknot and the katana. These are repeated in all of the art I viewed for this project. From each of these paintings, similarities can be drawn to Yoshida’s work, but it Yoshitoshi’s prints depicting injured samurai that have the most in common with the portrayal of warriors in the 20th century woodblock master’s “Profile of an Ancient Warrior.”

In Japanese wood block print there are a few dominant trends in their depictions of warriors. One trend is to display them as big burly characters that, though possessing samurai hairstyles and equipment, have nothing in the way of refinement. This is contrasted with the almost effeminate depictions of samurais that, apparently, have image consultants making sure that each piece of armor and clothing matches. Though looking like pretty boys the artists still give the impression that they can fight. In addition there are many depictions of samurai with horrific wounds. All of these images highlight the samurai dual nature of the sword and brush. They are both well-trained warriors and well read poets.

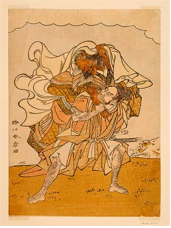

This dual nature lends itself to idealized portrayals of warriors displaying refinement, yet prowess on the battlefield. At the right is an Utagawa Kuniyoshi woodblock print entitled “Profile of a Warrior” made during the mid-19th century, this samurai has several long flowing kimonos on that would make combat difficult. Though he is in the middle of a battle and being shot at with arrows, his hair is not ruffled. He is not flustered, but calm as he takes down a straw barrier filled with arrows. In some woodblock prints it is hard to tell these calm effeminate warriors from women. Due to his abstract technique it is hard to say if “Profile of an Ancient Warrior” has much in common with prints of the “romanticized” warrior genre. Yoshida’s warrior’s topknot is intact even though it looks like he has been scalped. It is interesting that in the mayhem of the painting the only thing that is in focus is the black topknot that connects both warriors. I do not think that the printers who portray samurai unruffled in battle truly think this is how they are, but they are tapping into the mystique of the samurai as zen warriors. Yoshida does this too and the warrior’s hair provides the audience with an anchor point towards understanding the rest of the painting. Once the viewers recognize the two samurai faces by their topknots, they can ask what the rest of the abstraction represents in this context.

In contrast to these effeminate samurai are the big burly warriors represented with features normally reserved for foreign barbarians. They have big noses. They are hairy with big bushy beards and hairy calves reminiscent of Bigfoot.

Their topknots are unkempt. They have hair like madmen, and expressions to match. They are always grimacing. There muscles bulge as if are always flexing all of their muscles at once. They carry swords denoting their samurai rank, but are often depicted engaging their enemies in wrestling matches. Another brutish samurai in a Yoritoshi wood block print is using a gun. There is no sense of a duel, no code of honor; theirs is the struggle of domination through beastly strength. Sometimes the artist takes it a step further and displays them in an ape like form. In “Night Attack on Sanjo Palace” the low status samurai doing the killing appear as monkeys as they butcher courtesans. This is a popular way to represent low ranking samurai warriors who to the artist must have seemed more animal than human. In “Profile of an Ancient Warrior” the samurai is definitely clean cut, but the action is one of chaos and the emotion evoked is one of barbarism. The barbarian warriors would feel for at home in the context-less maelstrom of action of violence.

|

|

|

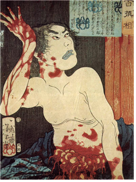

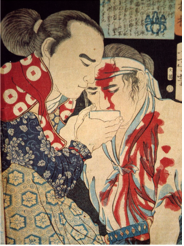

The abstract violence and bloodshed in “Profile of an Ancient Warrior” is very present in 19th century woodblocks of Japanese warriors with bloody injuries. On the left is a depiction of a samurai after a battle receiving water from a comrade painted by Yoshitoshi. The turmoil and subtle remorse in the wounded samurai, head bandaged and kimono bloodied, is captivating. On the right is a detail of “Profile of an Ancient Warrior” that instills a similar feeling, however, the pain in Yoshida’s samurai is a lot more real and immediate. The warrior mouths a scream, closing his eyes as hard as he can. In older woodblock prints the pain is distant, but no less real. The damage has been done and now the survivors are left to pick up the pieces. In a Kasunga Gongen scroll a warrior is left in a pool of his own blood, but he is at peace. In another Yoshitoshi wood block print a samurai is seen eating a rice cake with bloody hands and other wounds. A departure from this is a Yoshitoshi print from the series “Kwaidai Hyaku Senso,” which portrays hari-kari. The warrior is shown attempting to suppress his obvious pain and die nobly. I feel that Yoshida taps into the emotions and drama that these “wound” woodblock prints inspire. His placement of a grimacing warrior in the middle of the painting gives me the impression that he wanted to evoke these images with a bit of subtlety. Yoshitoshi’s prints are blunt hammers of human drama, but Yoshida, using his abstract techniques places the warrior’s pain in the middle of the chaos. Perhaps this represents the pain the Japanese people feel regarding World War Two, a pain that was bottled up and lost, unstable and frantic during the occupation years. Yoshitoshi lived during the Meiji Restoration, another turbulent period in Japanese history, and his prints reflect painful feelings. The change in the portrayal of a warrior’s pain is interesting; I think that Yoshida knew that his audience would not appreciate such gruesomeness.

Yoshida is also trying to find the primordial thread that wraps its way through all warriors. In doing so he takes cues from previous woodblock masters who depicted warriors in many ways. He uses the unruffled topknot of the refined samurai, the chaos and challenge evoked from brutish samurai depictions, and the human pain of injured warriors carrying on with their lives to create a compelling piece that has only revealed its secrets to me after careful study. His warrior is tranquil and at home in the chaos, but not untouched by the violence around him. Yoshida’s portrayal manages to embody everyone’s rendering of a warrior, and thus, I believe, has accomplished his goal of reaching into a primordial current that runs through us all.