The Yoshida Family

From One Generation to the Next

Over two centuries Japan’s economy, culture and people had been shut off from the rest of the world, but in 1853 the American Commodore Matthew Perry opened Japan’s ports to the United States and the rest of the world. These ports allowed for new inventions, ideas and ways of life to enter into and Japan. However, the Tokugawa government felt that the foreigners were invading and corrupting Japanese society. Likewise, Japan’s society was changed with the westernization of the country. At the end of the Edo era, the Tokugawa government was overturn during the Meiji Restoration were the Shishi overthrew the Bakufu and deposed the Shogun (Penelope Mason p. 343).

Moreover, at the same time period of the Meiji Restoration, the Japanese art world was heavily influenced by western society as well, especially with new artist like Yoshida Hiroshi learning modern art tactics. In the early 1900’s Yoshida Hiroshi “became a member of Meiji Bijutsukai (Meiji Fine Arts Society) and, with other artists, later reorganized the society as Taiheiyo Gakai (Pacific Ocean Painting Circle)” and that was the same time that Japanese prints took a modern identity.

Unlike some artists, Hiroshi Yoshida took great pride in his art work, for he was a perfectionist who always wanted to increase his skills more than other artists and more than his employees. For instance, “sometimes he carved the blocks for his prints; at other times he combined pigments for color shades and tone that were difficult to create before instructing his printers … to create subtle and soft colors he took three times the painstaking effort of the ukiyo-e masters” (Ogura Tadao, p. 8). When Hiroshi Yoshida wanted something done right, he would do the work himself. This characteristic along with his skills made him a creative genius who was able to apply new concepts to his foundation of traditional methods learned from other teachers like Koyama Shotaro.

In 1907 Yoshida Hiroshi married Fujio, the daughter of his adoptive father Yoshida Kasaburo (Yasunaga Koichi p.24). Fujio was an artist herself who did excellent color work for woodblock prints. Hiroshi and Fujio had two sons named Toshi and Hodaka, who would be the next generation of fine woodblock print scholar artists to carry on their parents’ work.

When Hiroshi Yoshida would travel around the world to find different landscapes to depict in his woodblock print art work, he would take his son Toshi Yoshida along with him for support and training. Just like Hiroshi, Toshi was a hard worker always learning and looking for new innovative way to contextualize his art work, whether it’s by colors or different shapes.

Likewise, Toshi said, “I observed my father’s painting method. He began his drawing in a different place on each canvas. He first drew outlines with a brush and quickly completed the drawing in a perspective composition. Then he painted the most important part in colors. Matching the tone of the colors with the essential part, he gradually filled the canvas with colors. When the whole canvas was covered with colors, the painting was completed. He avoided retouching. Once a picture was drawn or painted, it stayed as it was. He carefully completed works so that they would not require any further layering of colors” (Yoshida, Toshi p.29).

These learning experiences help shape and develop Toshi life as an artist and were Hiroshi’s way of passing on his artistic style to his son and the following generation of artists to come.

Furthermore, Toshi’s favorite subjects was landscapes and animals, just like his father and he used colors in distinctive ways much like his father used. Toshi exercised his opportunity to study at various art institutions in the United States. Likewise, “Toshi reached the same level of fame as his father did. His works are in the collections of all “big name” museums like the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Boston Museum of Fine Arts or the British Museum” (Helen Merritt and Nanako Yamada). Just because Toshi became as famous as his father, the prices of both of their art works are not the same, because Toshi’s prints are not as expensive as his father’s prints. In fact, a good Toshi print only ranges from 200 to 500 U.S. dollars.

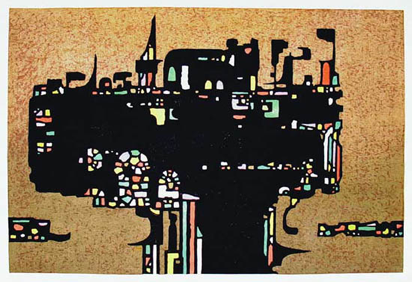

The 1967 “Hope” woodblock print is one example of the creative and innovative works of Toshi. He used a wide range of colors to depict different images within the large image, using straight lines followed by sharp curvy line to illustrate angles.

In conclusion, the United States forcing Japan to open its border to the rest of the world lead Japanese culture, society, economy and art to become up to date with the rest of the world, allowing artists like Hiroshi and Toshi Yoshida to become famous worldwide, depicting images of historic places all over the world. With that world exposure, Hiroshi and Toshi Yoshida were able to sell their woodblock prints to museums in American, Britain, China and other parts of the world without the Tokugawa government intervening. In addition, Hiroshi and Toshi were able to study art in other countries around the world.

Work Cited

Helen Merritt and Nanako Yamada, “Guide to Modern Japanese Woodblock Prints: 1900-1975”, published by University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu http://www.artelino.com/articles/toshi_yoshida.asp

Ogura Tadao, Toshi Yoshida, Yasunaga Koichi, “The Complete Woodblock Prints of Yoshida Hiroshi,” Tokyo: Abe Shuppan, 1991.

Penelope Mason, “History of Japanese Art,” New Jersey, Pearson Education Inc. 2005.

Ogura Tadao, The Complete Woodblock Prints of Yoshida Hiroshi, Tokyo: Abe Shuppan, 1991. p. 8