The Real Toshi Yoshida

As John Koening, from the movie Space: 1999, once said, “It is better to live as your own man than as a fool in someone else’s dream.” This statement is the issue that Toshi Yoshida had to face as a developing artist under the influence of his father, Hiroshi. The Yoshida’s family uses a prominent and traditional style for their artwork. For many years, Toshi silently protested for freedom to choose what he wanted in his own art. Whether it was the theme of his artwork or his personal style, he had to go through his father first. Hiroshi was a demanding father wanting to shape Toshi’s art into a second-generation version of his own, but Toshi secretly opposed this pressure by avoiding ther romanticism that exemplified his father’s work, and choosing subjects different from his father’s landscapes.

The Yoshida family is almost a one-family art movement. The first artist in the Yoshida family line was Kosaburo Yoshida; he went to a western art school, and his incredible work demonstrates the Italian influence in Japanese art. Kosaburo only had daughters, and among them was Fujio, who was also a talented artist. Nevertheless, Kosaburo adopted as a son whom later became his son in law, the promising young man who became the famous artist Hiroshi Yoshida. Hiroshi worked primarily as a painter until his late forties when he became fascinated with woodblock printing. Fujio and Hiroshi had two sons, Toshi and Hodaka, who carried on the family’s artistic line.

Toshi was born on July 25, 1911 just two months before his older sister Chisato, a three year old girl passed away. For the next fifteen years Toshi lived a lonely life, for he was the only child, until his brother Hodaka was born. According to Hiroshi’s plan, Toshi would become the artist, while Hodaka was meant for a career in science. Sadly, when Toshi was a child he contacted polio meningitis from his nanny’s family, which paralyzed one of his legs. This tragic incident played a big role in Toshi’s life as an artist because as a young boy he was not allowed to play outside with other children. Thus, Toshi spent his free time making art and inventing animal stories. According to Kendall H. Brown, “Toshi also routinely sketched with his parents, who taught him the rudiments of life drawing” (73). Toshi was taught at an early age the beauty of art.

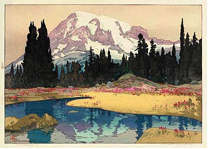

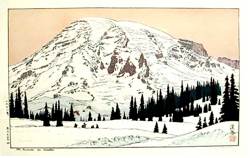

Toshi was the individual that Hiroshi would most deeply imprint with his sense of natural beauty and light. Kandall H. Brown mentioned that Hiroshi was Toshi’s teacher and ‘most ardent critic, sought to mold Toshi and his art into a second-generation version of himself and his own highly successful naturalism’ (73). This explains why most of Toshi’s artwork is similar to his father’s because Hiroshi wanted Toshi to fellow his technique. Still, it was hard for Toshi to please his father while trying to find and maintain his own identity. Toshi once stated that he chose to put his interest in animals because his father’s interest was in landscape; this was a way to differentiate his work from his father’s. Kandall H. Brown stated that, “viewers who are familiar with Hiroshi’s naturalistic landscapes often see Toshi as an artist who never fully emerged from his father’s shadow” (72). Perhaps it is that Toshi often painted and made prints of many of the same subjects that Hiroshi used. For instance, the two versions of Mt. Rainier, one created by Hiroshi and another created by Toshi.

|

|

| Mt. Rainier by Hiroshi Yoshida | Mt. Rainier in Winter by Toshi Yoshida |

These two images can be mistaken as by the same artist because it is very closely done with a similar media and technique. However, Bob Rhoades points out the differences of these two images by saying, “The image of the mountain in springtime with lavender covered hillsides caught as a moment of romantic revere by Hiroshi. Toshi’s image is a cold prominence in blues and grays capturing the stark strength of the dominant rock” (Rhoades). Toshi tried to distinguish his work from his father’s by choosing a different season or mood for the image, moving away from the romantic aspects of his father’s work.

Toshi carefully avoided the profound atmosphere and overt romanticism that exemplified his father’s work. In this way, he could distinguish himself while still staying within the style and subject that his father approved of. Brown mentions that, “Toshi’s avoidance of dramatic atmosphere and painterly effects marks an opposition to his father’s print style; the resolutely peaceful and non-symbolic subject also seems to reject the nationalistic images that most other Japanese artists were producing” (74). By doing so, Toshi is secretly expressing his independent values through his work. In an interview later, Toshi said, “ My father loved the mountains, so I turned to the sea” (75). Toshi could only secretly oppose his father by still keeping his father’s focus on the natural, but choosing a different division of nature. For example, in the image Tokyo at Night: From Ryogoku Bridge, Toshi made the image with sharp lines and clear tones. He making the image realistic, yet it has little details within the building.

From Tokyo at Night: Ryogoku Bridge by Toshi Yoshida

From Tokyo at Night: Ryogoku Bridge by Toshi Yoshida

It was not until Hiroshi’s death in 1950 that Toshi could really break away from his father’s demands. In order for Toshi to break away from his father’s naturalism and his past, he resigned from his father’s Pacific Painting Society to join with his brother’s group called Plus. Toshi moved into abstract art because his brother Hodaka, who had also become an artist, influenced him. Abstract art was a new and different style to Toshi. Therefore, he found himself within abstraction.

Although Toshi Yoshida was strained to become the second-generation version of Hiroshi, his father, he eventually broke away by secretly avoiding romanticism and purposefully contradicting his father’s artistic values. Toshi opposed his father through his artwork with his independent values of what was important to show his audience. The result was a unique type of art where Toshi’s true character came out.

Sources

Laura W., Kendall H., Eugene M., Matthew, and Koich. A Japanese Legacy: Four

Generations of Yoshida Family. Minneapolis, Minnesota: The Minneapolis Institute of Arts, 2002.

Rhoades, Bob. “The Yoshida Family Show: Three Generations of a Printmaking

Dynasty.” Mendocino Art Center andArts & Entertainment. 1999. August 1997.

<http://www.mcn.org/A/mendoart/ae/aug97/yoshida.html >

Skibbe, Eugene M. Yoshida Toshi: Nature, Art And Peace. Edina, Minnesota: Seascape

Publications, 1996.

Statler, Oliver. Modern Japanese Prints. Ruthland, Vermont: Charles E. Tuttle

Companey, 1956.