The Dinner Party

The Dinner Party: Judy Chicago

by Hannah Prichard

Biographical Context of Judy Chicago

Judy Chicago is one of the most renowned female artists of this century. Born in Chicago IL on July 20, 1939, she is a prominent artist, author, feminist, educator, and intellectual. Her works have been exhibited all over the world including the USA, China, Europe, Asia, Australia, and New Zealand (Judy Chicago). Judy pioneered a feminist art and art education program at California State University which she has continued to develop over the years. Some of her famous works include the Birth Project, PowerPlay, the Holocaust Project: From Darkness into Light, and Resolutions: A Stitch in Time (Judy Chicago). Judy’s work critically examines the gender construction of masculinity and explores the definitions of power that have affected the western world (Judy Chicago). She also examines power and the powerless in regard to her Jewish heritage. Her most widely known and admired project and the one we are going to examine is the Dinner Party which was developed between 1974-1979. This piece required the participation of hundreds of volunteers and is permanently housed in the Brooklyn Museum as the centerpiece of the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art. Not only is Judy Chicago a feminist worth studying but this piece of art opens a dialogue of hundreds of feminists throughout the history of western society.

Judy Chicago is one of the most renowned female artists of this century. Born in Chicago IL on July 20, 1939, she is a prominent artist, author, feminist, educator, and intellectual. Her works have been exhibited all over the world including the USA, China, Europe, Asia, Australia, and New Zealand (Judy Chicago). Judy pioneered a feminist art and art education program at California State University which she has continued to develop over the years. Some of her famous works include the Birth Project, PowerPlay, the Holocaust Project: From Darkness into Light, and Resolutions: A Stitch in Time (Judy Chicago). Judy’s work critically examines the gender construction of masculinity and explores the definitions of power that have affected the western world (Judy Chicago). She also examines power and the powerless in regard to her Jewish heritage. Her most widely known and admired project and the one we are going to examine is the Dinner Party which was developed between 1974-1979. This piece required the participation of hundreds of volunteers and is permanently housed in the Brooklyn Museum as the centerpiece of the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art. Not only is Judy Chicago a feminist worth studying but this piece of art opens a dialogue of hundreds of feminists throughout the history of western society.

The Dinner Party

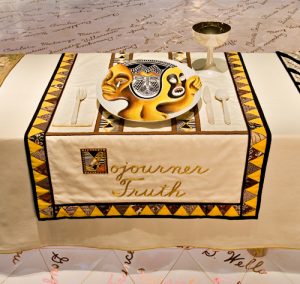

The Dinner Party was a massive piece of artwork that required the help of 400 volunteers including 23 people helping Chicago continuously. The piece consists of 39 individual place settings and 999 names inscribed in gold on a 2,304 porcelain tiled Heritage Floor (Brooklyn Museum). Judy Chicago was originally looking at 3,000 possible female names to include on either the floor or the place settings. Six hanging banners made using traditional woven tapestry techniques introduce the work. The centerpiece of the work is a triangular table atop the Heritage floor. Each side holds 13 intricately designed place settings that represent strong female historical figures. The place settings include porcelain flatware, a porcelain chalice, and a porcelain plate placed on an embroidered table runner.

The Dinner Party was a massive piece of artwork that required the help of 400 volunteers including 23 people helping Chicago continuously. The piece consists of 39 individual place settings and 999 names inscribed in gold on a 2,304 porcelain tiled Heritage Floor (Brooklyn Museum). Judy Chicago was originally looking at 3,000 possible female names to include on either the floor or the place settings. Six hanging banners made using traditional woven tapestry techniques introduce the work. The centerpiece of the work is a triangular table atop the Heritage floor. Each side holds 13 intricately designed place settings that represent strong female historical figures. The place settings include porcelain flatware, a porcelain chalice, and a porcelain plate placed on an embroidered table runner.

The main purpose of The Dinner Party is to reclaim the history riddled with the sole recognition of male heroes. Chicago uses Christian themes in this piece to trace this male dominating culture back to Jesus and the Last Supper. Each side of the table houses 13 individuals the same number of disciples that attended the Last Supper (Brooklyn Museum). She also uses the literal meaning of women having a place at the table while pointing to the traditional and historic place of women cooking in the home. In addition, each plate is decorated to resemble the female vulva, used to symbolize the power of the female body. The plates are raised and lowered along the table to signify the rise and fall of feminist achievements. The decorations on the plates then start to lift up off the surface with the rise of the international feminist movement in the 19th century to signify the start of liberation.

The main purpose of The Dinner Party is to reclaim the history riddled with the sole recognition of male heroes. Chicago uses Christian themes in this piece to trace this male dominating culture back to Jesus and the Last Supper. Each side of the table houses 13 individuals the same number of disciples that attended the Last Supper (Brooklyn Museum). She also uses the literal meaning of women having a place at the table while pointing to the traditional and historic place of women cooking in the home. In addition, each plate is decorated to resemble the female vulva, used to symbolize the power of the female body. The plates are raised and lowered along the table to signify the rise and fall of feminist achievements. The decorations on the plates then start to lift up off the surface with the rise of the international feminist movement in the 19th century to signify the start of liberation.

Here is a brief youtube video of Judy Chicago discussing the piece and the general concepts she strives to achieve through this piece.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tskczrGpESA

Judy Chicago researched female heroes extensively to inform her work and respectfully portray these women. She referenced John Maw Darton’s 1880 Famous Girls Who Have Become Illustrious Women of Our Time: Forming Models for Imitation by the Young Women of England and Mary Hay’s Female Biography, or Memoirs of Illustrious and Celebrated Women of All Ages and Countries (Brooklyn Museum). When she was researching for the project the Mary Hay’s book hadn’t been checked out for 65 years. This just speaks to the need for a project like Chicago’s. Light needed to be shed on these women’s accomplishments.

The final destination of The Dinner Party was not the original intended permanent home. The original home was supposed to be a government-affiliated university that needed approval from Congress (Brooklyn Museum). Congress ruled the work as pornographic and inappropriate in an academic setting. Even now, Judy Chicago’s piece receives criticism for being explicit and inappropriate. This is most likely due to the societal culture surrounding the female body as an object of admiration and purity but not one of power and sexuality.

The piece was finished in 1979 and largely rooted in second-wave feminism, meaning that it did not include transgender women or many women of color. Judy Chicago has since stated “our choices were limited by language barriers, fragmented information, and our own inexperience and biases. Our intention, however, was not to define women’s history but to symbolize it – to say that there have been many women who have done many things, and they deserve to be known” (Brooklyn Museum). The curators at the Brooklyn Museum are trying to open this narrative by inviting LGBTQIA+ artists into this conversation and metaphorically bringing these artists to the table (Brooklyn Museum). I believe that if this project were done today we would have a much grander and more representative sample of great women.

There are only four women of color at the table – Sacajawea, Sojourner Truth, Kali, and Hatshepsut – three of which we will examine more deeply.

Women of Color at the Dinner Party

Sacajawea is one of the most powerful Native American women of all time. She accompanied her husband, Charbonneau, on the famous expedition led by Merriwether Lewis and William Clark in 1804. Her name means “Bird Woman” in Hidatsa (Brooklyn Museum). She was only sixteen years old and pregnant when they started the journey. Even though Charbonneau was the one asked to join them, Sacajawea became a huge asset to Lewis and Clark. She spoke Shoshone and Hidatsa which enabled her to translate to Native American tribes along the way (Brooklyn Museum). She was also very familiar with the Yellowstone area and knew about the food sources in the area. Sacajawea gave birth and then carried the infant on her back for the entire expedition. She became an icon of bravery and strength. Her seat at the table is characterized by the cultural traditions of the Shoshone tribe (Brooklyn Museum). The plate is decorated with geometric shapes and Chicago incorporated the butterfly and triangle which are often present in Native American iconography. At the top of the plate are a beaded cradleboard and hood which is meant to reference Sacajawea’s perilous journey with her infant on her back. The table runner is made out of deerskins which are bordered with 40,000 opaque seed beads. The final ornament is the intricate “S” of her name which references its meaning in Hidatsa, “Bird Woman.”

Kali is a goddess that can be traced back to East India from the first millennium B.C.E. She is now worshipped throughout Southeast Asia, primarily in Bengal, India (Brooklyn Museum). Kali is a goddess of fertility and time and is meant to be both feared and adored. She is also associated with creation, salvation, and having the ability to give new life and take it. She enforces justice by killing anything that threatens the purity of life such as evil, ignorance, and egoism (Brooklyn Museum). This both vicious and nurturing figure is depicted with four, eight, or ten arms and her crazed facial expression and wild hair have a sense of violent energy. Judy Chicago designed Kali’s plate to symbolize the cycles of nature and reference the fertile nature of the female body using vulva imagery filled with seeds (Brooklyn Museum). The table runner emphasizes Kali’s power over death using iridescent fabrics and layers to look like human flayed skin. She is no doubt a powerful figure for women.

Sojourner Truth was an abolitionist and suffragist who was one of the most powerful voices in the fight for equality in the US. At the age of eleven, then named Isabella Baumfree, was sold to John Dumont in New York (Brooklyn Museum). After being promised freedom but then denied it, she ran away with her youngest child. Believing she had a calling from God to fight for others’ rights, she gave herself a new name: Sojourner Truth. Sojourn means to travel and truth was meant to be the truth of God (Brooklyn Museum). She devoted her life to helping the disenfranchised by counseling black soldiers and teaching slaves domestic skills. She also worked tirelessly to help black soldiers get jobs after the war had left them homeless. At a rally organized by Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Truth was Frederick Douglass’s guest. She ended up giving the famous “Ain’t I a woman” speech. In the speech, she declares that women are not inferior to men and they deserve the right to vote (Brooklyn Museum). Judy Chicago did not follow her normal vulvar imagery on Sojourner Truth’s plate that she did on the others. Instead, she used three faces, in the style of African masks, each with a powerful and historical statement (Brooklyn Museum). The left face weeps for the suffering of the slaves and is marked by a tear running down her cheek. The right face represents the outrage of black women due to being enslaved. The last face in the middle is meant to show that both black and white women were meant to conceal their true selves. The three faces share the same body which is indicated by the breasts at the bottom of the plate. The table runner uses traditional weaving techniques used by slaves and throughout African heritage. The edge weaving is combined with a piece-working technique imported by European women (Brooklyn Museum). The combination represents the merge of these two traditions.

I challenge you now to think of a woman who would make a needed addition to Chicago’s piece. How would you incorporate historical elements from their past onto a surface like a plate? How would you tie those elements to a table runner that would enhance their narrative? Judy Chicago started something using this project. She opened up possibilities for studying women and I don’t think she intended the conversation to stop with only the women represented here.

Helpful Links for further investigation

Judy Chicago’s Website page: https://www.judychicago.com/gallery/the-dinner-party/dp-artwork

The Brooklyn Museum’s page: https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/exhibitions/dinner_party

A list of the women who had a place at the table is here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Dinner_Party

Page constructed by Hannah Prichard

Sources

Judy Chicago. Chicago/Woodman LLC, https://www.judychicago.com/. Accessed 1 May 2020.

“Kali.” Brooklyn Museum, https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/eascfa/dinner_party/place_settings/kali. Accessed 1

May 2020.

“Sacajawea.” Brooklyn Museum, https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/eascfa/dinner_party/place_settings/kali. Accessed 1

May 2020.

“Sojourner Truth.” Brooklyn Museum, https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/eascfa/dinner_party/place_settings/kali. Accessed 1

May 2020.

“The Dinner Party.” Brooklyn Museum, https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/eascfa/dinner_party/place_settings/kali. Accessed 1

May 2020.