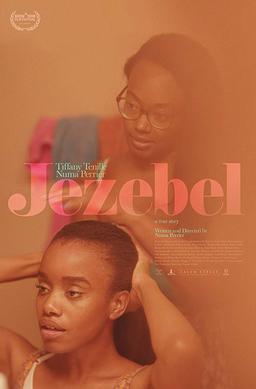

Jezebel (2019)

by Kirsten Anderson

Overview

Taking place in modern day Las Vegas, Jezebel (2019), directed by Numa Perrier, is a film about a young woman named Tiffany who moves in with her older sister Sabrina and younger brother Dominic during the last days of their mother’s life. Desperate to find a job, Sabrina, who is a phone sex operator, points her sister in the direction of an office where she could become an internet cam girl. At 19 years old, Tiffany takes this job and begins to discover her own sexuality and liberation through her work, though it does not always prove to be easy, as she is the victim of blatant racism in her workplace, which is the space in which she can escape the evolving, challenging circumstances of her outside world. Between her troubles at work and the grief of losing her mother, Tiffany grapples with many coming-of-age emotions, and she must keep working and pushing through it all to afford to support herself after being kicked out by her sister. This revolutionary film tells the true story of a sex worker dealing with racism, sexism, grief, and sisterhood, all forcing her to grow up more quickly than the average young woman. Jezebel provides audiences with a raw story they cannot find elsewhere, shedding light on very real, prevalent social issues and the ways in which they intersect, engaging black feminism, misogyny, racism, and gender-related wealth disparities. Central themes of this piece are one’s existence as a woman and the challenges faced as a result of gender, especially in regards to the stigmatization of sex work, growing up, and the added barriers of being black.

Available on Netflix

Grief

The first theme present is grief. Tiffany, Sabrina, and Dominic lose their mother to illness and must carry on by themselves. While they try to support each other, there is much conflict between them as they process their feelings and frustrations about their loss, and it becomes instantly clear that their grief is placing a strain on them, challenging their relationships with one another, especially across lines of gender, as most arguments take place between Dominic and one of his sisters who are expected to fill their mother’s shoes.

Sisterhood

Throughout the conflict that is set up at the beginning of the film, the viewer begins to see Perrier’s development of sisterhood as a central focus, beginning with the simple plot point of Tiffany moving in with Sabrina. It is the first example viewers see of Sabrina and Tiffany supporting each other through tough times to remain strong. Next, we see Sabrina helping Tiffany find a job in addition to helping her find outfits and other items for her use at work– this is Sabrina’s way of helping her younger sister foster confidence and empowerment through her sexuality. Through their interactions, we can see Sabrina taking an almost motherly role in helping Tiffany find herself as an adult, exuding a nurturing, caring type of sensitivity and affection. Perrier employs these traits to show the value of women helping women and the strength of taking care of people, as is stereotypically a woman’s role. Through the displays of sisterhood, she pushes the narrative that it is not a weakness to care for others, but rather the opposite– it is radical and strong to be nurturing and caring because that is what true sisterhood and solidarity is all about.

Sexism

Next, we begin to see the theme of sexism develop throughout the scenes, and it is mainly present in two places: the home and her work. In their home, Dominic makes incessant remarks about how he thinks their sex work is disgusting and shameful and constantly makes it clear that he is vehemently against it, as he sees it as “slutty.” He very clearly sees sex work as an exploitative act, not in that it is wrong, but in that it is meant to please men, and therefore it makes them whores for embracing their bodies and sexuality. Additionally, we witness Sabrina’s boyfriend saying quite oversexualizing things to Tiffany when they are alone, displaying the sexism of the objectification of women. As for life in the workplace, her sex work company is completely run by a man who constantly polices what his female workers can and cannot do with their bodies, whether they are in front of the screen or not. They must act a certain way on screen, perform just the right way, and look flawless, all things which are being dictated and observed by a man. Perrier is not trying to say men shouldn’t run these businesses– she is making a social commentary on the objectification of women through beauty standards and the policing of their bodies through the telling of Tiffany’s story.

Furthermore, the theme of sexism is driven home by Tiffany being treated more harshly than her brother. Sabrina tells her sister that she must find her own place and financially support herself now that she is working. While this in itself is not unreasonable, the issue lies in that Sabrina does not enforce the same rule on Dominic, even though he has a job as well and could support himself. This challenge in the plot demonstrates how women are treated more harshly than men and how they must always take responsibility. As a result of being kicked out, Tiffany must learn to grow up much faster than her brother does and take care of herself in ways she should not have to at just 19 years old. Additionally, Perrier makes a point of how women are expected to be caretakers simply because they are women by showing how Sabrina coddles Dominic and her boyfriend while she is stuck taking care of the house and the family. The clear dichotomy of the responsibilities and expectations of women versus men forces viewers to understand the sexist disparities that exist, and this is true to an even greater degree for black women, who are expected to carry the burden of others.

Racism

Finally, Numa Perrier tackles the massive hindrances that come from racism in a raw, challenging way. An overarching idea here is that of black success. This provides viewers with a commentary on how black people, and women in particular, do not get the same employment opportunities as their white counterparts; they must work twice as hard to achieve the same level of success as a white person, and that is contingent on whether or not they can even find a job, which proves difficult due to systemic barriers targeting black people and women. Tiffany, having both of these identities, is very limited in what options she has for work, especially being low-income, which takes away from the idea of black women being professional and successful even though systemic barriers created these blockades in the first place. This cam girl job was the only one she could get quickly enough to support herself, showing the limitation black people have when searching for employment.

Tiffany encounters the hardships of her race in a major way when she faces significant adversity at work. Generally she is fetishized by customers for being the only black woman on the site, and she is oversexualized because of white men’s internalized prejudice which sees black women as more elusive, animalistic, and exotic. It’s pretty clear why this is racist. Additionally, one of her coworkers insists Tiffany’s massive success must be the result of her doing something illegal on camera, referencing the stereotype that black people are criminals, because in the white coworker’s mind, a black woman could never be more successful than her just by playing by the rules. This plot point displays her clear white superiority complex, which is so deeply ingrained into the minds, interactions, and institutions of white people.

In an even more explicit manner, Tiffany grapples with the racist words and notions of her boss, coworkers, and customers when a customer calls her the N-word in a chat box. When she rightfully gets upset and says he must be removed because of his unacceptable action, she is not taken seriously by her coworkers or boss. They both essentially tell her to forget about it and move on, as if a racial slur is not to be taken seriously. When challenging her coworker on this notion, Tiffany receives the response that all the other women deal with the same thing being called “worthless whores,” and her boss refuses to block the man from the site on the grounds that he is a “good customer.” These instances are both clear deflections of the impact of Tiffany’s race and an attempt to prove the oppression of others.

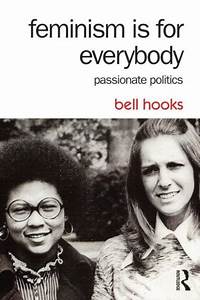

Connection to Feminist Texts

When viewing this film, I thought of bell hooks’ Feminism is for Everybody, specifically the chapter on race and gender. On page 57, hooks says, “white women who were unwilling to face the reality of racism and racial difference accused us of being traitors by introducing race. Wrongly they saw us as deflecting focus away from gender,” which I think has a clear tie to this aforementioned incident. The coworkers are trying to equate her struggles and experiences as a black woman to white women being called derogatory names, as if that erases the impact of Tiffany’s blackness. The response of the coworkers is nothing more than a racist attempt at ignoring the customer’s and their own racism and shifting the focus onto themselves as white women who are supposedly just as oppressed, and this directly links to hooks’ claim. Lastly, hooks says, “we knew that there could be no real sisterhood between white women and women of color if white women were not able to divest of white supremacy” (58), which proves to be relevant to Tiffany’s discovery that these women were never her friends. They never cared about her or her struggles as a black woman, and they didn’t want to acknowledge such a fact. There is an explicit connection between these two texts from different time periods, pointing to the fact that the oppression of the black woman has not changed, and it will not change with white women standing in the way, ready to deflect the struggles of blackness at any moment.

Final Thoughts

This film explores a myriad of important themes, and I argue they are all extremely relevant to the world today. Perrier creates a beautifully raw depiction of the personal and social implications of being a black woman in sex work, especially while trying to juggle her responsibilities with her grief of a huge loss, and it is such an important piece of art that we should all experience and dwell on.

Sources

hooks, bell. “Race and Gender.” Feminism Is for Everybody: Passionate Politics, 2nd ed., Routledge, 2014, pp. 55–60.

Perrier, Numa, director. Jezebel. House of Numa, 2019.