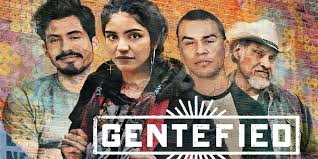

Gentefied: Bringing Latinx Experience, Reality, & Intersectionality to Screen

Gentefied: Bringing Latinx Experience,

Reality, & Intersectionality to Screen

by: Daisy Tucto

Introduction

As a new wave of Latinx programming hits more and more platforms, the 2019 Netflix Original Series “Gentefied”, was first produced and created by Marvin Lemus and Linda Yvette Chavez in 2016 as a short-form web series. It was entered into the Sundance Film Festival when it caught Netflix’s attention and was eventually turned into a full series!

Gentefied sheds (long overdue) light to the relatable, historic, and contemporary intersectionality aspects of how many first-generation Latinxs live their lives and embrace their Latinidad. At the same time, that experience allows the audience to see the difference in generational views, struggles, and triumphs as the characters try to achieve the American Dream in hopes to gain social mobility and overcome prejudices from their communities.

You may be wondering what does “Gentefied” or “Gente-fication” even mean? Well, to simply put it, it’s a new term that combines the Spanish word gente (meaning people) and gentrification to mean accommodating outside communities by trying to improve your own area/community. In this sense, it yells the significance of gentrification’s effects in reality, where working-class people, usually people of color, are strategically and forcefully removed/displaced from their neighborhoods by increasing living costs to “economically improve” areas.

Important Vocabulary

- Acquiescence – Reluctant acceptance without protest

- Affinity – Natural liking or sympathy for someone/something

- Barrio – Neighborhood

- Gentrification – Process of renovating and improving a house/district to conform to middle/upper-class taste for their move in

- Heterosexism – “The belief in the inherent superiority of one pattern of loving and thereby its right to dominance” (Audre Lorde).

- Homophobia – “The fear of feelings of love for members of one’s own sex and therefore the hatred of those feelings in others” (Audre Lorde).

- Intersectionality – Interconnected nature of social categorizations that create overlapping/interdependent systems of discrimination or disadvantage

- Latinx – Gender neutral or nonbinary term for a person of Latin American origin/descent

- Matriarchy – State of being an older, powerful woman in a family/group

- Racism – “The belief in the inherent superiority of one race over all others and thereby the right to dominance” (Audre Lorde).

- Taqueria – Taco shop

- Tokenism – Practice of symbolically recruiting a small number of people from underrepresented groups to give the appearance of sexual/racial equality

- Queer – “An umbrella term that can be used by anyone under the LGBTQ spectrum” (Sophie Thomas).

Historical/Contemporary context of gentrification

There’s a long history of gentrification in the United States, and it would take me a long time to tell you about every neighborhood or city that has gone through this vicious process. It’s no secret that gentrification in cities maintains racial inequality and segregation. Boyle Heights, California where Gentefied takes place has a long-standing battle with gentrification. Before WWII Boyle was ethnically diverse, but in the 1920s, restrictive covenants legally prohibited people of color from buying or living in certain neighborhoods (Estrada, 2018). Even after laws like the Fair Housing Act in 1968, “the government failed to end discriminatory zoning practices” (Estrada, 2018). Today, gentrification in Boyle Heights has grasped a lot of media attention because of the low property values, 25% median rent increase, and anti-gentrification community protests like posting mock eviction notices in gallery events (Estrada, 2018). Still, areas concentrated with people of color in low-income communities are targets of gentrification as historical legacies of racism and capitalist pressures are pushing working-class residents out of Southern California.

Summary of Gentefied

The show starts off with a captivating pilot episode introducing the main characters and their dilemmas. This bilingual story follows three Mexican-American cousins: Ana Morales, Erik Morales, and Chris Morales, and their elder relatives. Throughout the series, they try to create their own paths, balance their cultural traditions, identity, and threatening gentrification.

Taking place in a barrio of Boyle Heights, California (2019), the cousins’ grandfather (Pop) owns a family taco shop and the landlord intentionally doubles rent prices to kick them out of the area in hopes to rent it to more “wealthy” tenants. Unable to afford the rising prices, Pop and his grandsons are forced to change the taqueria to accommodate to the changing local economy/community and bring in money to help them save their taqueria.

Chris helps Pop spice up the restaurant’s menu by creating hybrid tacos to appeal to new customers, “preppy Californians”. Meanwhile, Erik and his ex-girlfriend, Lidia, try to figure out their relationship situation, with their baby on the way, and Erik tries to regain Lidia’s love back in hopes of forming a family. And Ana is also trying to handle her own pile of troubles as she begins to work for a wealthy white gay man, Tim, who buys real estate, raises property values, and pays Ana to paint murals/artworks to “beautify” (GENTRIFY) Boyle Heights district to attract a “new affluent crowd”. During her gallery showcase event, Ana realizes that her girlfriend, Yessika, was right. Tim and his friends are using her to paint murals on buildings (with images that are not accepted by her Latinx community) to bring in white and rich people/tourists. So, like a badass, instead of presenting her art pieces to satisfy the directors and propel her career, she writes over her centerpiece painting: “RAZA NOT FOR SALE”! And mic drops with: “Y’all gentrifying motherfuckers can kiss my ass.” You should really watch season one before season two comes out!

Character Rundown

- Beatriz Morales (Mother): Represents the matriarchy as a hard-working Mexican-immigrant, single mother, and head of the household raising and providing for her two children. As a patternmaker and garment worker, she has to complete exaggerated quotas. Beatriz struggles financially to support her family with her job that pays below minimum wage to undocumented workers. She and other women work long hours with no lunch/restroom breaks, plus unpaid overtime, for low wages, and are scared to go to the union meetings because of their undocumented status. She also doesn’t support Ana’s aspiring dream to become an artist, but towards the end of the season, she accepts Ana’s passion for art and supports her decision to pursue a career in art. This mother figure represents the older Latinx working-class generation, who have immigrated to the United States in hopes of attaining the “American Dream”, as she overcomes societal limitations and barriers to help her family financially survive.

- Ana Morales (Daughter): First-generation Mexican-American and 24-year-old Chicana, who is a young struggling, woke, and queer Latinx artist trying to catch her big break into the mainstream “art world”. She tries to balance her life between her girlfriend, artwork, and helping her mother work overtime at home. She works for Tim, who openly tokenizes Anna to his friends and colleagues, reiterating how she is “a queer Chicana from a low-income community”, completely diminishing her identity to being one-dimensional and speaking for her. He puts her life and identity on blast for those around him to be mesmerized over the exotic, fresh, and ethnic queer artist that he has “discovered” and is so generously helping build her career. But really, he just wants to look good in front of the gallery board of directors, who are also wealthy property owners in Boyle Heights trying to gentrify the area with Ana’s artwork. Despite really needing the money to help her mother out, she stood up for herself and did not go through with selling her talent to further gentrify her community.

Connection to Feminist Texts

Ana Morales’ Mural

There are many themes in this series, however, a theme that is continuously involved behind the process of gentrification in Boyle Heights, which is a predominantly Latinx populated neighborhood, is sexuality and homophobia. Although Ana is very open about her relationship with her girlfriend Yessika, the mural she paints on Tim’s building depicting “Brown Love” (an image illustrating two brown male luchadores kissing) is not approved by the Latinx people in the community. It is especially rejected by that building’s liquor store owner, who is an elderly Latinx woman with conservative views. The mural causes conflict between people in the neighborhood and causes the elderly lady to lose a lot of business.

Bringing our attention to feminist authors and Ana’s employment situation with Tim, one Chicana feminist author, Norma Alarcon, talks about the tokenization, psychosexual exploitation, and economic exploitation of women and Chicanas. Alarcon asserts, “As women we are and continue to be tokens everywhere at the present moment… female tokenism: that power withheld from the vast majority of women is offered to a few” (Alarcon). We see this tokenization with Ana and economic exploitation with Beatriz as they both try to improve the quality of their lives.

Having the opportunity to represent Ana’s queerness in her hometown places her at a crossroads in her community. Lesbian poet and feminist writer, Audre Lorde, talks about the homophobia, racism, and sexism in her book “Sister Outsider” saying, “The supposition that one sex needs the other’s acquiescence in order to exist prevents both from moving together as self-defined persons toward a common goal”. This relates back to how in the middle of disapproving Ana’s mural, everyone in the community forgot and was blinded by the sexual identities and differences instead of seeking solidarity in a common cause against the gentrification happening around them.

Another feminist Chicanx author, Gloria Anzaldùa, in her excerpt called “La Prieta” calls out everyone in the Latinx community on the internalized racism and fear of women and sexuality. As she talks about growing up queer and feeling “abnormal” to her family, she proclaims that, “We are the queer groups, the people that don’t belong anywhere, not in the dominant world nor completely within our own respective cultures. Combined we cover so many oppressions… [and] with my own affinities and my people with theirs can live together and transform the planet” (Gloria Anzaldùa). I love this because Gloria underscores the oppression she experiences as a queer woman of color. In this sense, the people in Boyle Heights should not cast stones, but place importance on unifying people regardless of different identities/sexuality so that there can be change to recreate and restructure society.

Conclusion

Being a first-generation Ecuadorian-American, I felt deeply connected and visible through this show because there are so many themes of race, class, gender, and sexuality that are often not talked about enough in the Latinx community. The strong Latinx women characters represented in this show depict such relatable real-life experiences with racism, homophobia, and financial hardships of undocumented workers. This fresh view into the lives of Latinxs who are working hard to make a living, seeking acceptance from society, and struggling to establish their own identity emphasizes how many Latinxs try to find acceptance in between worlds in which they feel “not American enough” and “not Latinx enough”.

There are no studies or surveys that can truly captivate and make people feel what others’ personal experiences are like. Narratives and storytelling are ways to keep those experiences alive, and that’s what Gentefied did. It told a Latinx narrative. It brought it to our screens. And it brought it to life.

.

.

.

.

Works Cited

Anzaldúa, G., & Moraga, C. (2015). This bridge called my back: writings by radical women of color. Albany: SUNY Press.

Calvario, L., & Ngo, C. (2020, January 26). ‘Gentefied’: Everything to Know About Netflix’s New Latinx Dramedy. Retrieved from https://www.etonline.com/gentefied-everything-you-need-to-know-about-netflixs-new-latinx-dramedy-140109

Cuby, M., Meronek, T., Clark, C., & Brammer, J. P. (2020, February 21). “Gentefied” Tackles Gentrification With Humor and Authenticity. Retrieved May 8, 2020, from https://www.them.us/story/gentefied-gentrification-netflix

Estrada, G. (2018, December 12). The Historical Roots of Gentrification in Boyle Heights. Retrieved May 8, 2020, from https://www.kcet.org/shows/city-rising/the-historical-roots-of-gentrification-in-boyle-heights

Estrada/Netflix, K. (2020, February 21). They Felt Like Hollywood Outsiders. Then They Got a Netflix Show. Retrieved from https://www.vulture.com/2020/02/gentefied-netflix-creators.html

Gallaga, O. (2020, February 19). Gentefied: What You Need To Know About Netflixs New Latinx Dramedy. Retrieved from https://www.primetimer.com/features/gentified-what-you-need-to-know-about-netflix-s-new-dramedy

Hwang, J. (2014, August 5). How “Gentrification” in American Cities Maintains Racial Inequality and Segregation. Retrieved from https://scholars.org/contribution/how-gentrification-american-cities-maintains-racial-inequality-and-segregation

Lorde, A. (2001). Sister outsider: essays and speeches. Trumansburg, NY: Crossing Press.

Sager, R. (2017, November 15). Gentrification in L.A.’s Boyle Heights Leaves Some Latinos Threatened, Others Hopeful. Retrieved May 8, 2020, from https://www.nbcnews.com/news/latino/gentrification-l-s-boyle-heights-leaves-some-latinos-threatened-others-n820381

Thomas, S. S. (2019, September 26). What Does It Really Mean to Be Queer? Retrieved from https://www.cosmopolitan.com/sex-love/a25243218/queer-meaning-definition/