Overview

A Brief History of Crepe-paper Books

What are Crepe-paper Books?

Crepe-paper books, or chirimen-bon (ちりめん本), are a unique style of Japanese woodblock-printed publication. They were first devised and printed by innovative Tokyo publisher Hasegawa Takejirō in the Meiji period (circa 1888).

Unlike plain-paper Japanese woodblock prints, crepe-paper books have a unique appearance and tactility. The wavy, crinkled surface of the paper feels almost soft or fabric-like in the hand. This “creped” appearance was a key part of the books’ marketability and the result of a labor-intensive process. Plain-paper prints had long served a domestic Japanese audience, although their popularity in the Meiji period waned in light of new technologies like photography and lithography. In light of increasing interest in “traditional” Japan abroad (termed Japonisme), Hasegawa sought to export these works from the very beginning. Although our collection here at St. Olaf College focuses on Hasegawa’s fairy tale publications, he also branched out into other kinds of literature, such as poetry and descriptions of Japanese life and culture. He felt that these topics combined with the innovative nature of crepe would surely appeal to Western women and their children. The reach of crepe-paper books was broad, however, and crepe-paper books even entered the collection of artist Vincent Van Gogh.

One fascinating aspect of crepe-paper book production is the collaborative process through which they were made and translated. Hasegawa often worked with English-speaking authors– such as David Thompson, Basil Hall Chamberlain, Kate James, and Lafcadio Hearn–to write the text of his publications. The illustrations were designed by Japanese woodblock print artists–such as Kobayashi Eitaku, Suzuki Kason, Mishima Shōsō, and Arai Yoshimune–often in consultation with the text. From there, the designs would have to be rendered into a woodblock print carving and printed by skilled woodblock printers. The printing of the text was often outsourced to local Tokyo letterpress printers with expertise in foreign languages like English, French, or German. Finally, the books would be bound and published before being shipped to various dealers in Japan and worldwide. Understanding crepe-paper books is often a practice in unpacking diverse communication networks.

Hasegawa focused on his crepe publications from 1888 until 1908, when he expanded his business to other publications such as calendars. Nevertheless, Hasegawa (and later his son, Nishinomiya Yosaku), continued to publish reprints of these books into the post-war period.

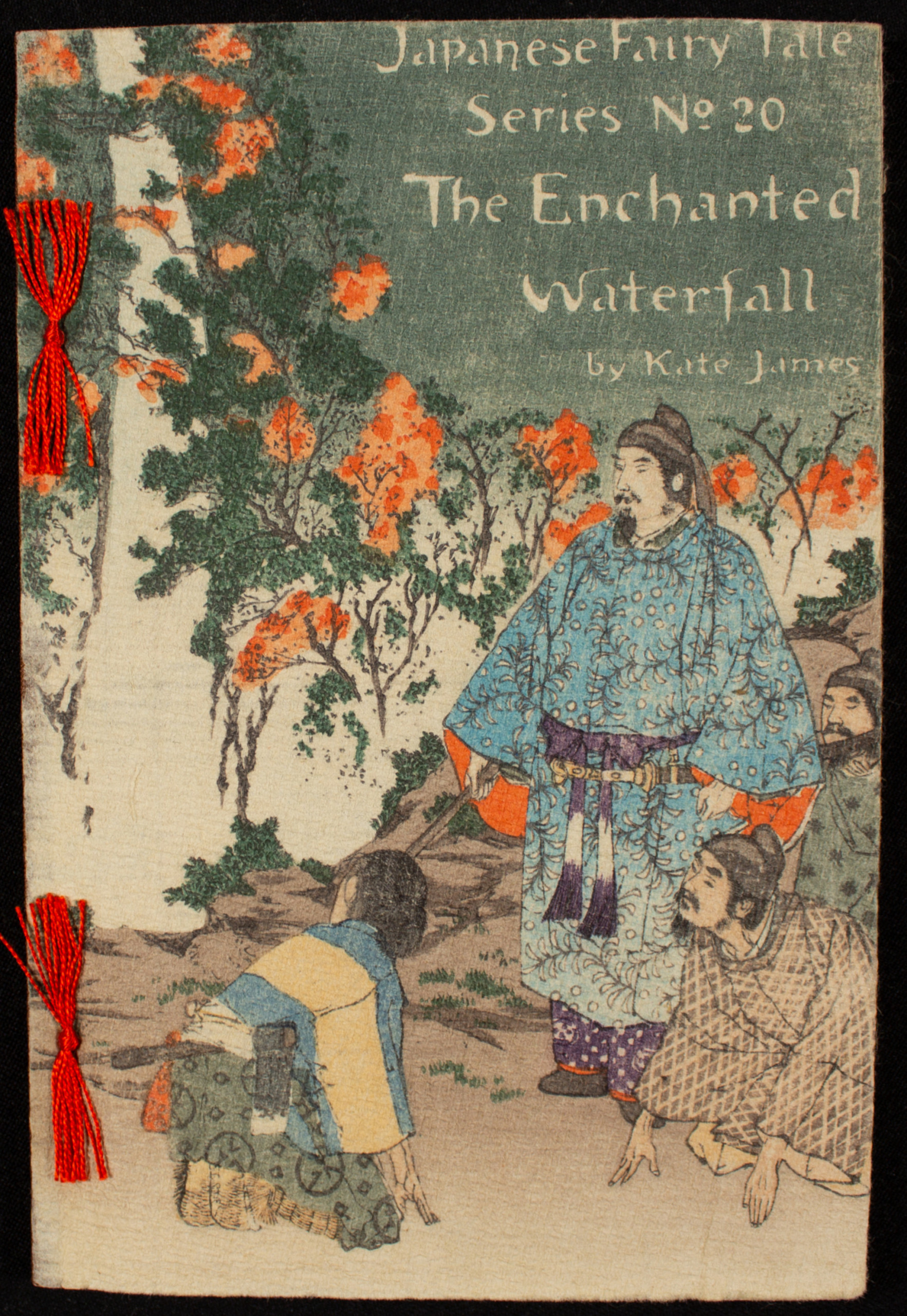

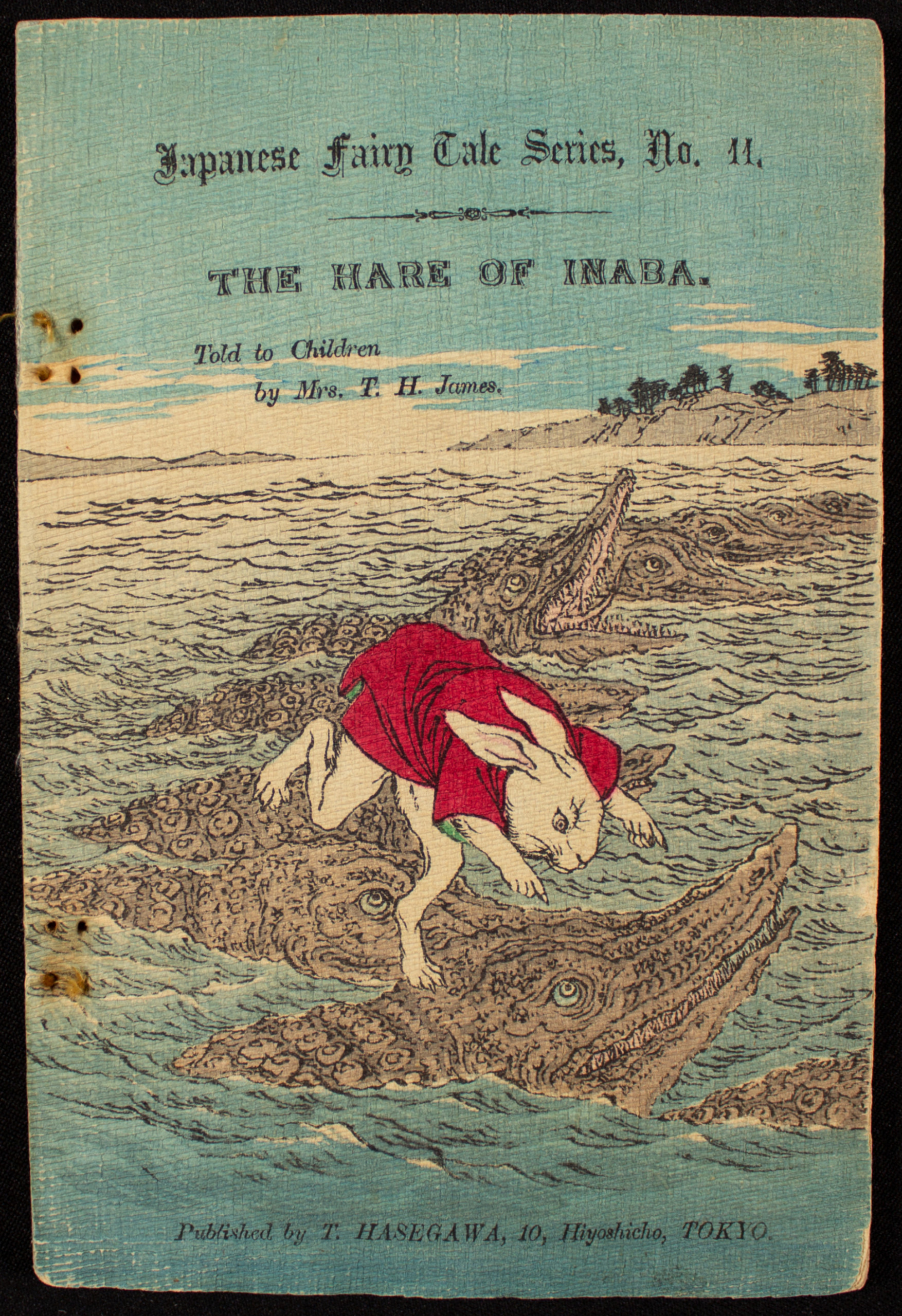

We have over 20 crepe-paper books in our collection here at St. Olaf College, including an early version of The Hare of Inaba (no. 11) and a later reprint of The Enchanted Waterfall (no. 20).

“What I wanted to say is that I have seen Hasegawa, the publisher of the Fairy-Tale Series, and learnt from him that he has latterly been paying $20 per tale… One thing to be remembered is that he is not omnivorous. Only a single tale at a time in his view of things, each taking long to illustrate, and various other circumstances causing delay…”

—Letter from Basil Hall Chamberlain to Lafcadio Hearn (June 20, 1894), p. 137

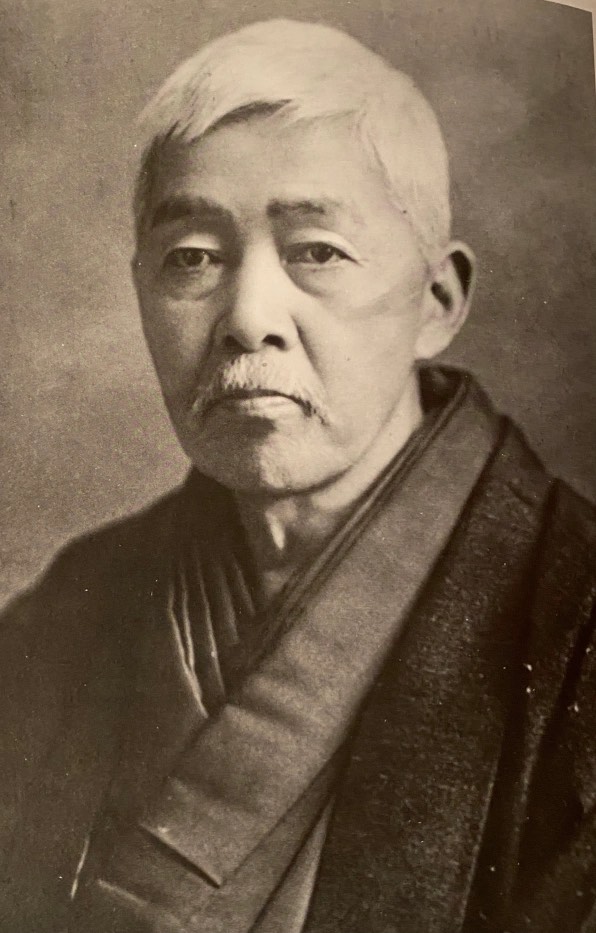

Image: Publisher Hasegawa Takejirō (1853-1938). Photograph from University of Maryland Libraries.

Who is Hasegawa Takejirō?

Hasegawa Takejirō, born October 8th, 1853, spent his formative years studying English and business. At 17 years old, Hasegawa had begun to form connections with the local Protestant missionary community, attending church and learning to read English. This community was key to the beginning of his work in the publishing industry, with several individuals contributing translations for him to work with. He was baptized by Rev. David Thompson in 1880; however, his Christian activities ended relatively quickly after an economic recession in 1881. Nonetheless, he remained very connected to the missionaries, who would provide translations, stories, and requests for publications throughout his career. Hasegawa was constantly on the move, always looking for the next product, and most importantly, maintaining personal supervision over each and every project. The first few years of his activities laid the groundwork for later success, and he was quick to evolve and update his products when needed. The publication of his Japanese Fairy Tale Series in the unique chirimen-gami, or crepe-paper medium, is the most significant of his works. He worked with multiple translators and artists to create nearly 30 different stories, which were available in several different languages. His English copies were the most prolific and contained the largest catalog of stories. A careful reading of the surviving first-hand accounts of Hasegawa’s business tactics reveals a man who not only knew how to navigate the challenges of the publishing and export markets but also one who prioritized connecting and nurturing the relationships he had with those around him, regardless of their status and profession.

“--With regard to the types. In view of the shrinkage of the paper, I should certainly say that the heavy black-faced type is the best for the crêpe edition. It would give a clear effect even after shrinkage, and so help the children’s eyes. On the other hand, for plain paper printing, it is a little too heavy for the size of the page. So I should say that the light-faced type would look best for the large page; and the heavy dark type for the crêpe edition,--in which its heaviness will disappear by the chirimen process."

—Letter from Lafcadio Hearn to Hasegawa Takejirō (Sept. 28, 1898), p. 318

Hasegawa's Collaborators

In addition to working with many different Japanese artists, woodblock printmakers, and letter-press foundries, Hasegawa also maintained many connections to the community of foreigners living in Tokyo and Yokohama. A study of these connections yields a fascinating picture of a changing Meiji Japan. Below are some of the various individuals involved in the production of Hasegawa’s English-language fairy tales. For a full account, please check out Hasegawa’s Social Network.

Translators

Artists

“Though it is convenient to speak of these stories as ‘fairy-tales,’ fairies properly so-called do not appear in them. Instead of fairies, there are goblins and devils, together with foxes, cats, and badgers possessed of superhuman powers for working evil. We feel that we are in a fairy-land altogether foreign to that which gave Europe ‘Cinderella.’…”

—Basil Hall Chamberlain, Things Japanese (1905), p. 155

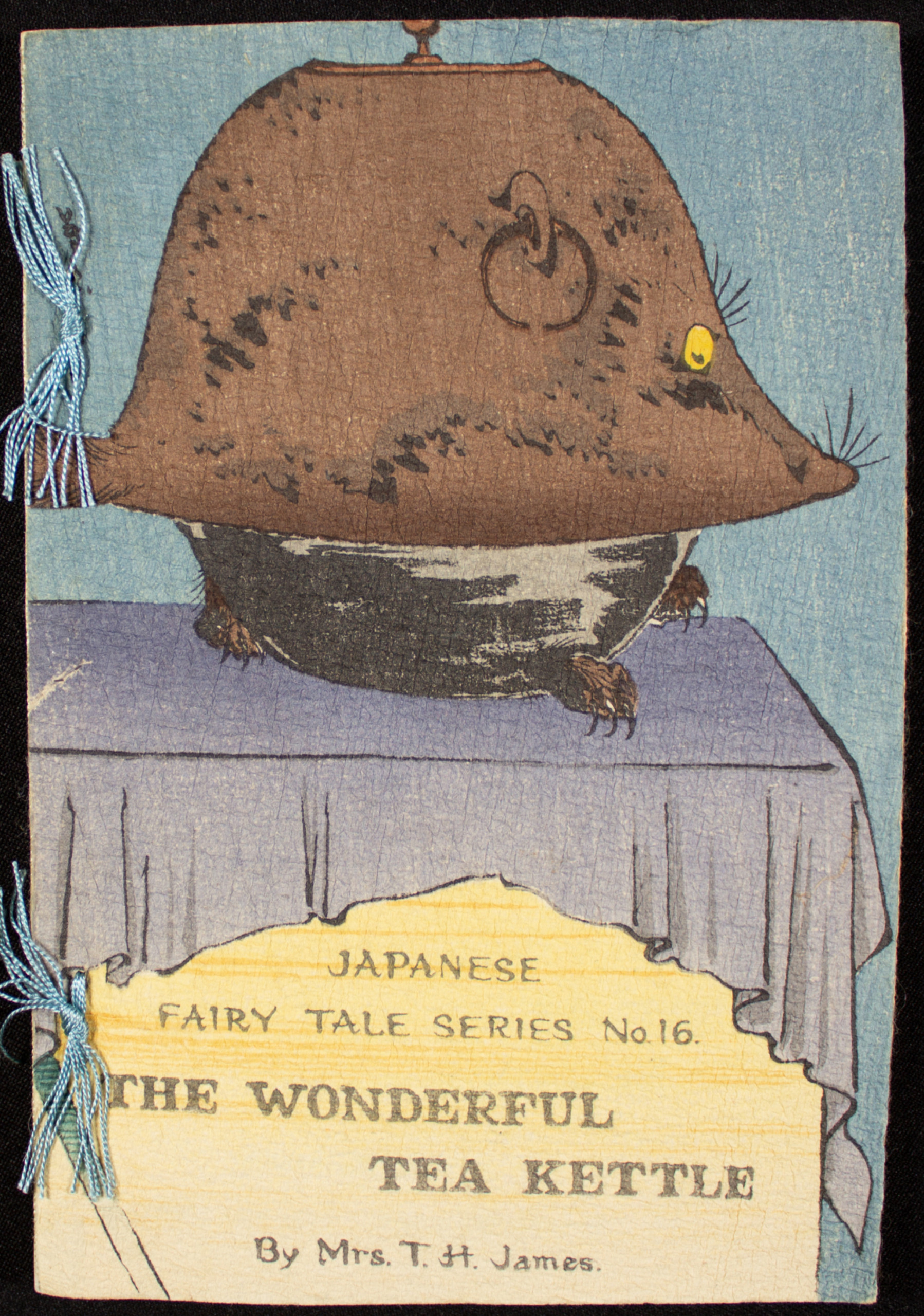

Bunbuku Chagama is a Japanese folktale or fairy tale about a tanuki, that uses its shapeshifting powers to reward its rescuer for his kindness.

Japanese Fairy Tales

Even though Hasegawa uses the broad term “fairy tales” for his series, they were generally not intended as “bedtime stories” for children. The stories are quite diverse in origin and did not form a cohesive “series” in Japan. Many stories were derived from texts composed as early as the 8th century, such as the Kojiki, the Nihon Shoki, or the Man’yōshū. Other stories originate in Noh theater or vernacular folktales.

The English “translations” in Hasegawa’s fairy tales are authored by Anglophone writers who have likely heard or read the Japanese tale from other sources and translated them in a way that Western readers would understand. (For example, the tanuki in Kachi-Kachi Mountain is translated as a badger in David Thompson’s retelling of the story). From what we can understand from letters between Basil Hall Chamberlain and Lafcadio Hearn, Hasegawa tended to solicit work from his authors, one story at a time. As a result, we can see real differences in the tone and rhetoric of each writer.

Versions of these fairy tales in other languages, such as German, Dutch, Spanish, French, or Russian, tended to be based on the English translation.