Essay: On the Value of Mapping

by Christina M. Spiker

Essay

Concretely mapping Hasegawa Takejirō’s addresses and business connections was not an original part of the research plan when Laura Smith ‘25, Anika James ‘25, and I began this project in the Summer of 2024. But with each Japanese crepe-paper fairy tale we opened, it became increasingly clear that Hasegawa’s physical location was always an essential part of the story we wanted (and needed) to tell.

Hasegawa Takejirō conducted business at six different addresses, the dates of which have been documented by Frederic Sharf.1Frederic A. Sharf, Takejiro Hasegawa: Meiji Japan’s Preeminent Publisher of Wood-Block-Illustrated Crepe-Paper Books, vol. 130, nos. 4, 130, 4., Peabody Essex Museum Collections (Salem, Mass: Peabody Essex Museum, 1994), 77.

1. 2 Minami Saegi-chō, Kyōbashi-ku, Tōkyō (from August 1885-1889)

東京府京橋区2南佐柄木町

2. 3 Maruya-chō, Kyōbashi-ku, Tōkyō (May 1889-1890)

東京府京橋区3丸屋町

3. 10 Hiyoshi-chō, Kyōbashi-ku, Tōkyō (December 1890-1901)

東京府京橋区10日吉町

4. 20 Honzaimoko-chō, Nichōme, Nihonbashi-ku, Tōkyō (March 1901-1902)

東京府日本橋区20本材木町二丁目

5. 38 Honmura-chō, Yotsuya-ku, Tōkyō (September 1902-1911)

東京府四谷区38本村町

6. 17 Kami Negishi-chō, Shitaya-ku, Tōkyō (June 1911-)

東京府下谷区17上根岸町

The name of his business also shifted over time from Kōbunsha to T. Hasegawa, and after looping his teenage son Nishonomiya Yosaku into the business in 1914, Hasegawa & Son, or Nishinomiya & Hasegawa. After Hasegawa’s passing in 1938, books were often published solely under his son’s name as Y. Nishinomiya. While it is often difficult to date Hasegawa’s crepe-paper publications due to the reuse of blocks and pages,2Jacob Blanck, Bibliography of American Literature (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1955), 75. the presence of an address on a publication can often give readers an estimate of the earliest possible publication date. The building associated with Hasegawa’s final location at 17 Kami Negishi-chō is extant today with a historical marker.

There are both opportunities and challenges when working with Meiji and early Taishō-era material, like Hasegawa’s crepe-paper books. The positive when working with woodblock prints or woodblock/letterpress-printed books is that publishers almost always included the full street address of their shop. These addresses not only pinpoint a location; they also attest to the history of their business. In an urban environment like Tokyo, location (and, by extension, ward) matters. The Japanese colophons of these books also occasionally give addresses for the woodblock or letterpress printer and, less commonly, the artist or the writer.

But challenges exist, too. Tokyo has gone through dramatic changes since the Meiji era, notwithstanding the 1923 Great Kanto Earthquake. These events also impacted Hasegawa’s business. According to Lafcadio Hearn’s biographer P. D. Perkins, “The 1923 earthquake destroyed Hasegawa’s office-workshop and when they resumed work at their home in Kami Negishi they must have had to cut many new blocks. Much work both before and after the earthquake was done at their home and unfinished and partly finished work was kept at the house which when I saw it was a cluttered-up mess. They would discover some pages in a forgotten corner. Copies with the pre-earthquake colophon would be more likely to be complete or part first or early printings. A woodblock print expert could probably come very close to deciphering what copies had all or nearly all early printed pages. The paper used might also have varied slightly…”3Blanck, 75. Aside from the very real impacts on Hasegawa and Nishinomiya’s publication business, there are also tangible impacts on Tokyo itself. The earthquake forced a major city redistricting, making contemporary maps almost useless when locating historical addresses. Finding these locations on historical maps forces the viewer to practice patience and close looking.

Our project overlays two different Meiji historical maps from similar periods on top of a contemporary projection of Tokyo using ArcGIS.

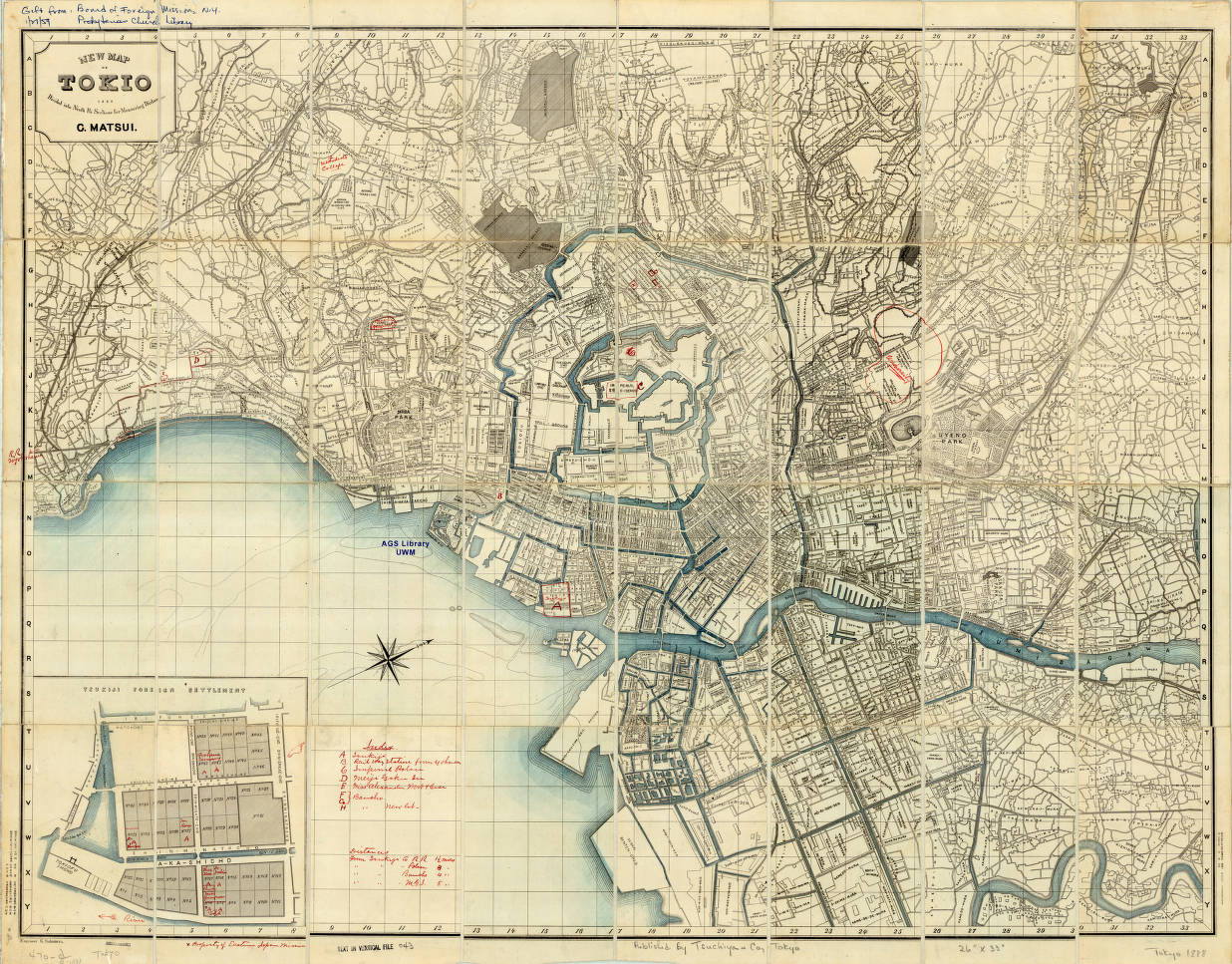

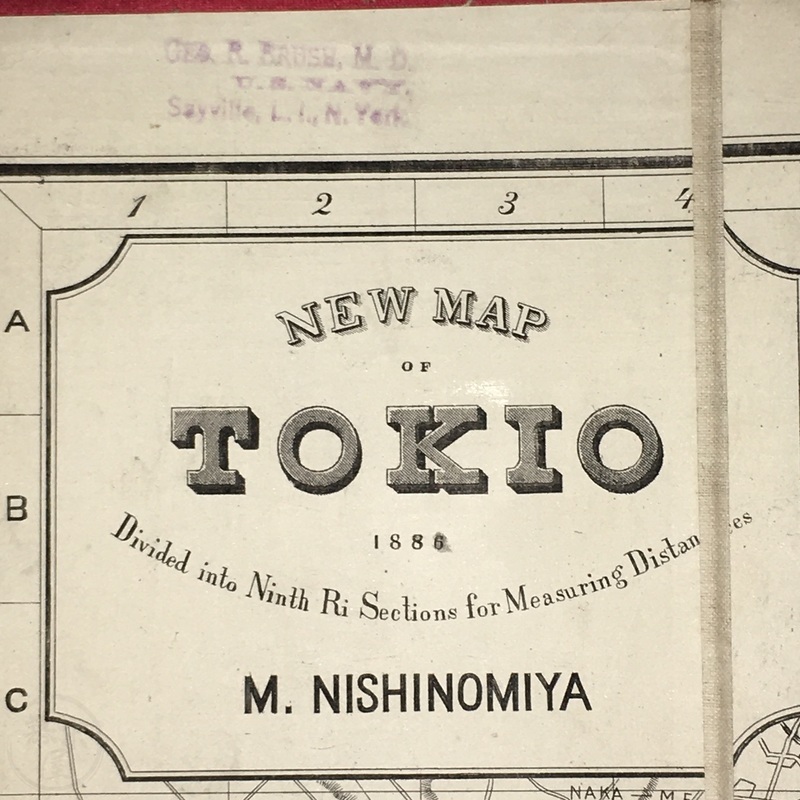

The first map is the annotated 1888 New Map of Tokio: Divided into Ninth Ri Sections for Measuring Distances by C. Matsui, engraved by G. Nakamura, and published by Tsuchiya & Co.4“New map of Tokio : divided into ninth ri sections for measuring distances / C. Matsui ; engraver G. Nakamura ; published by Tsuchiya & Co.” American Geographical Society Library Digital Map Collection, University of Wisconsin Milwaukee Libraries. Accessed 18 July, 2024. https://collections.lib.uwm.edu/digital/collection/agdm/id/2407/ The map is entirely in English, and details the Tsukiji settlement and the whole of Tokyo in great detail. A version of this very map was reproduced in Frederic Sharf’s seminal work about Hasegawa Takejirō, which alone made it a good starting point for our project.5Sharf, Takejiro Hasegawa, 7. However, more recently, antiquarian bookseller Bakumatsuya listed a version of the very same map published earlier in 1886 by Nishinomiya Matsunosuke, Hasegawa’s older brother, under Hasegawa’s Kōbunsha imprint.6“New Map of Tokyo with 1,300 Cho References by Nishinomiya Matsunosuke” Bakumatsuya: Rare Books & Photos. Accessed 18 July, 2024. This connection is fascinating and shows the little-known reciprocation between Hasegawa and his brother documented in the scholarship of Ozaki Rumi.7Ozaki, Rumi, “Background to the Birth of Kobunsha’s Chirimen Book Series “European Japanese Old Tales’’ – Collaboration between Hasegawa Takejiro, David Thompson, and Kobayashi Eitaku (弘文社のちりめん本『欧文日本昔噺』シリーズ誕生の背景――長谷 川武次郎・デイビッド・タムソン・小林永濯の協働),” Studies of Research Center for Children’s Literature and Culture, Shirayuri University 23 (March 2020): 19–38.

Left: C. Matsui, New Map of Tokio: Divided into Ninth Ri Sections for Measuring Distances, 1888. Photograph by American Geographical Society Library Digital Map Collection, University of Wisconsin Milwaukee Libraries

Right: M. Nishinomiya. New Map of Tokyo with 1,300 Cho References, 1886. Photograph by Bakumatsuya.

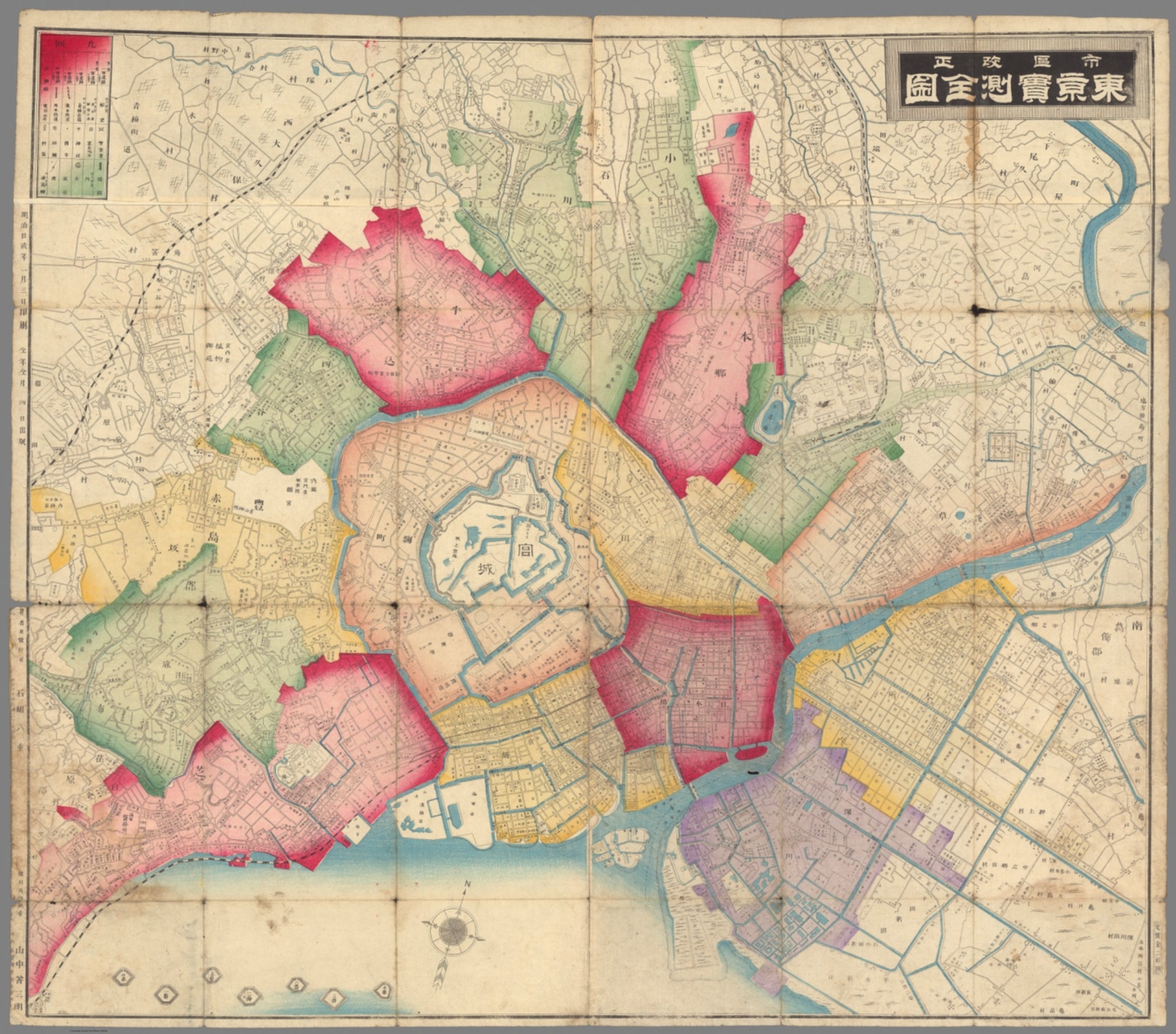

The second map is the 1889 [Complete Survey Map of Tokyo with Revised Wards] (市區改正東亰實測全圖) by Ishijima Yae and Yamanaka Yoshisaburō from the online collection of David Rumsey.8“市區改正東亰實測全圖 / [Complete Survey Map of Tokyo with Revised Wards]” David Rumsey Map Collection. Accessed 18 July, 2024. https://www.davidrumsey.com/luna/servlet/detail/RUMSEY~8~1~340606~90108860 According to Geographicus (2022), this was a folding survey map of Tokyo whose primary purpose was to highlight recent administrative changes in Tokyo, including the creation of Tokyo Municipality (東京市), composed of 15 wards (區), within the larger Tokyo Prefecture (東京府). This map likely would have been used in a government office for reference purposes. It was chosen as a contemporary counterpart to the previous example and has the added benefit of using woodblock-printed colors to distinguish between different wards.

Ishijima Yae and Yamanaka Yoshisaburō, “市區改正東亰實測全圖 / [Complete Survey Map of Tokyo with Revised Wards]” 1889. Photograph by David Rumsey Map Collection.

Within the digital humanities, the utility of a map is linked to one’s ability to interpret it and derive meaning from the connections that it shows. Plotting Hasegawa’s addresses on these maps shows a couple of concrete things about his business in Tokyo in the period between 1880 and 1911.

1. Hasegawa progressively moved away from his Kyōbashi-ku roots. In the beginning, when Hasegawa was not yet well known on the publishing scene, it was critical for him to be centrally located in either Kyōbashi-ku or Nihonbashi-ku, the commercial center of the city. For example, his address at 10 Hiyoshi-cho was walking distance from the Shimbashi Railway Station and the newly constructed Imperial Hotel.9Sharf, Takejiro Hasegawa, 12. As his business stabilized, Hasegawa moved further afield, first to Yotsuya-ku and then north of Ueno Park to Shitaya-ku–the studio he would stay at from 1911 until his passing in 1938.

2. Seeing these points on a map allows us a real appreciation of distance in narrative accounts of Hasegawa’s business. When Hasegawa left Kyobashi to find a printer, meeting “across the river” with Komiya Sōjirō in Oshiage-cho in 1884-1885, it would have been an hour and forty-one minutes on foot in contemporary Tokyo.10Ishizawa, Saeko, Meiji Illustrated Books in Western Languages: All About Crepe-paper Books (明治の欧文挿絵本 : ちりめん本のすべて), 2nd ed. (Tōkyō: Miyai Shoten, 2005), 218. After Hasegawa married Sōjirō’s daughter, Yasu, Hasegawa continued to use the Komiya family’s services and thus continued to make the long trip, likely by jinriksha. Other printers were much more local to Hasegawa at various moments in time. Notably, when Hasegawa Takejirō moved to 17 Kami Negishi-chō in Shitaya-ku, his longtime printer collaborator Kaneko Tokujirō was practically living next door. The neighborhood was known for its community of artists, writers, and craftspeople.11Sharf, Takejiro Hasegawa, 12.

3. We can see an increasingly diverse foreign presence in Tokyo that extends far beyond the Tsukiji settlement. When people consider the opening of Japan’s borders in 1854, they often think about the foreign community living in Yokohama. By the time Hasegawa started his business nearly 30 years later, the foreign presence was pretty entrenched not only in Yokohama, but also in Tokyo. Foreigners were not limited to the Tsukiji settlement, although that was certainly an important site, especially for missionary activity. Tracking the James family and other collaborators like Basil Hall Chamberlain and Lafcadio Hearn shows that they lived in diverse parts of Tokyo, primarily to the south and west of Chiyoda Castle. However, these communities were also in flux. The letters between Chamberlain and Hearn attests to the many challenges of relocation when communication was done primarily through correspondence.

4. We can also observe the connection between these foreign individuals and Japanese universities/institutions. Many foreigners in Tokyo were not there idly, they came for work, whether it was missionary activities, working for the Japanese government as oyatoi gaikokujin (“hired foreigners”), or working for private companies. Notwithstanding exceptions like Lafcadio Hearn, who deliberately resided far away from his place of employment (Tokyo Imperial University), many foreigners generally lived conveniently near their work.

There are indeed more insights to be gained by analyzing Hasegawa and his collaborators’ geographic space. We hope you will take the time to examine this website’s map(s). There is a real beauty and art to them! They will help you understand Hasegawa’s business from a slightly different perspective.

Works Cited

- 1Frederic A. Sharf, Takejiro Hasegawa: Meiji Japan’s Preeminent Publisher of Wood-Block-Illustrated Crepe-Paper Books, vol. 130, nos. 4, 130, 4., Peabody Essex Museum Collections (Salem, Mass: Peabody Essex Museum, 1994), 77.

- 2Jacob Blanck, Bibliography of American Literature (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1955), 75.

- 3Blanck, 75.

- 4“New map of Tokio : divided into ninth ri sections for measuring distances / C. Matsui ; engraver G. Nakamura ; published by Tsuchiya & Co.” American Geographical Society Library Digital Map Collection, University of Wisconsin Milwaukee Libraries. Accessed 18 July, 2024. https://collections.lib.uwm.edu/digital/collection/agdm/id/2407/

- 5Sharf, Takejiro Hasegawa, 7.

- 6“New Map of Tokyo with 1,300 Cho References by Nishinomiya Matsunosuke” Bakumatsuya: Rare Books & Photos. Accessed 18 July, 2024.

- 7Ozaki, Rumi, “Background to the Birth of Kobunsha’s Chirimen Book Series “European Japanese Old Tales’’ – Collaboration between Hasegawa Takejiro, David Thompson, and Kobayashi Eitaku (弘文社のちりめん本『欧文日本昔噺』シリーズ誕生の背景――長谷 川武次郎・デイビッド・タムソン・小林永濯の協働),” Studies of Research Center for Children’s Literature and Culture, Shirayuri University 23 (March 2020): 19–38.

- 8“市區改正東亰實測全圖 / [Complete Survey Map of Tokyo with Revised Wards]” David Rumsey Map Collection. Accessed 18 July, 2024. https://www.davidrumsey.com/luna/servlet/detail/RUMSEY~8~1~340606~90108860

- 9Sharf, Takejiro Hasegawa, 12.

- 10Ishizawa, Saeko, Meiji Illustrated Books in Western Languages: All About Crepe-paper Books (明治の欧文挿絵本 : ちりめん本のすべて), 2nd ed. (Tōkyō: Miyai Shoten, 2005), 218.

- 11Sharf, Takejiro Hasegawa, 12.