Technical Process

How Are Crepe-paper Books Made?

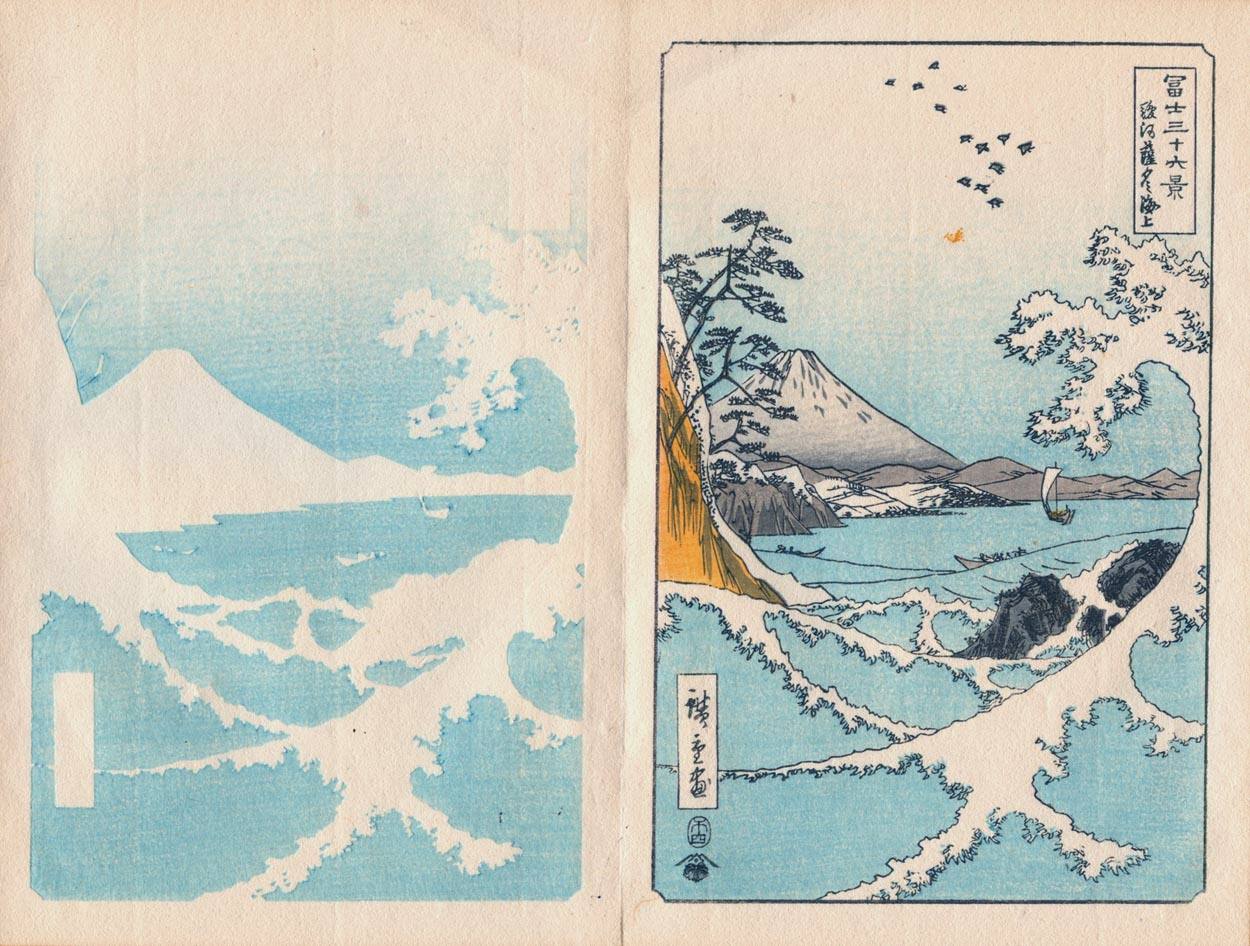

Top: Example of a keyblock carved by David Bull in 2012.

Bottom: Nishinomiya Yusaku, Process of Wood-block Printing (c. 1953). Photograph from Baxley Stamps.

Printing the Image

Before any paper could get the signature “crepe” treatment, the illustrations and text first had to be printed. There were two entirely separate processes for creating the images and text.

Book illustrations and covers were created through the polychrome woodblock printing process. This is a traditional relief printing technique refined in the Edo era that was used to create multicolored prints (nishiki-e) that became famous for their depictions of vibrant urban life (ukiyo-e). One thing that characterizes the woodblock print process is the division of labor–the process typically involves a range of professionals in collaboration. Historically, this included including artists, carvers, printers, and publishers.

To make a colored print, several carved blocks were needed. A “keyblock” served as a general black outline and several different color blocks would be use to create the various colors and tones. The example on the left from Nishonomiya Yusaku’s Process of Wood-block Printing (c. 1953) shows one single color block in isolation next to the finished print.

At this stage, no text was printed on the blocks.

Printing the Text

After the woodblock-printed images were complete, the text was printed via letterpress. This is a different relief printing process by which small letters or characters on metal plates were selected (bunsen) and arranged in a carrier (typesetting). The bunsen process is much easier for languages like English than it is for Japanese. The image carrier is inked, and the paper is pressed against the image carrier to transfer the image. Letterpress was still in use by publishers in Japan as late as 2003.

The letterpress process allowed the same woodblock-printed illustrations to be reused for books in a wide variety of languages, including French, German, Russian, and Portuguese. Very often, the printer involved in the woodblock printing and the letterpress printing were different individuals. Hasegawa often sub-contracted the printing of the text. He had relationships with companies like Shueisha, Tokyo Tsukiji Type Foundry, Seishi Bunsha, Bungyoka-sha, among others.

The paper was creped only after the illustrations and text were printed.

Top & Bottom: These two images are from the Ichigaya Letterpress Factory in Shinjuku. VIsitors can go on a tour of the factory and try their hand at bunsen through simulated experiences.

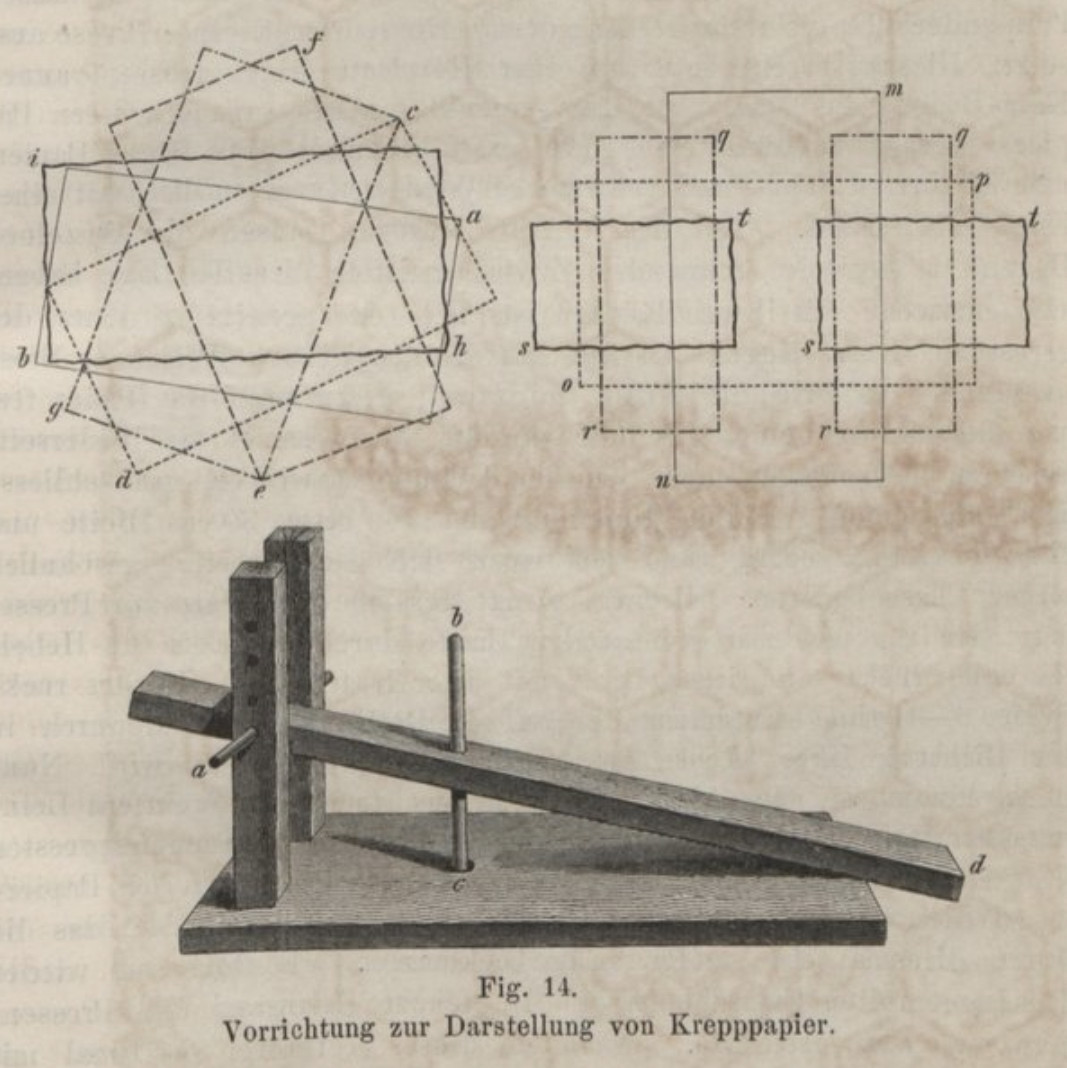

Image: Diagram of a momidai from Johann Justus Rein’s Japan nach Reisen und Studien (1886).

Making the Crepe

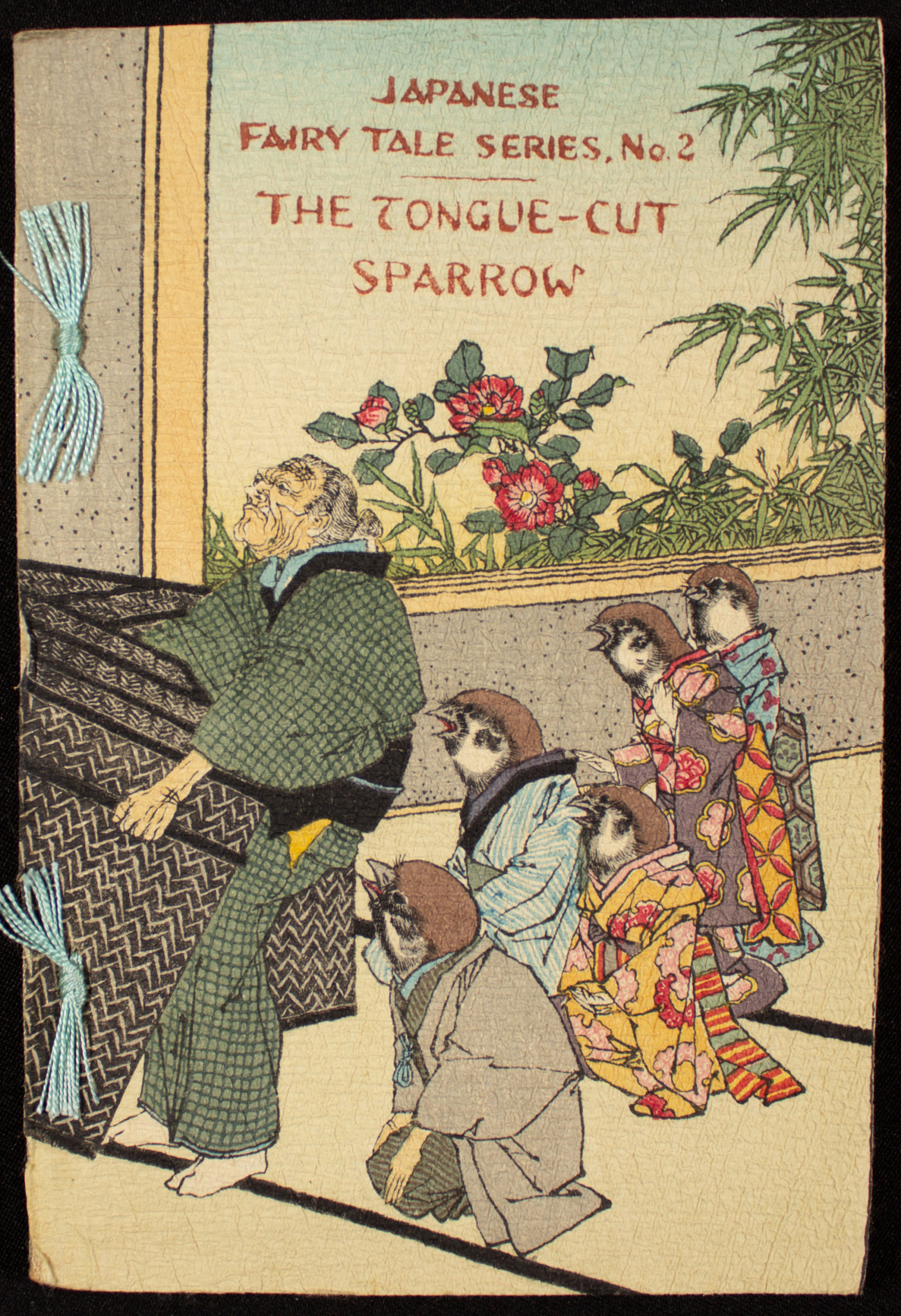

Once the pages were printed, they could either be bound as is or go through the process of creping. Hasegawa often released volumes in both creped and plain versions. The crepe paper was something that set Hasegawa’s publications apart from his competitors.

The paper was creped with a device called a momidai. The technology behind this was guarded by Hasegawa, so the process and device can only be approximated. The paper would be moistened and stacked in a specific way in between forms and then wrapped around a center dowel. Pressure from the lever above would compress the paper. This process would often be done several times to ensure the crepe texture for which Hasegawa is known. As the paper is creped, the image shrinks to 80-50% of its original size.

Click the button below to read about our attempt to recreate a momidai.

Creating the Binding

Finally, many of Hasegawa’s publications (both plain and creped versions) were bound in a traditional Japanese style with silk thread called musubi-toji (結び綴, lit. “Knot binding”). For Hasegawa, this involved folding single-sided printed pages in half and sewing the loose ends of those paper leaves together to form a rigid spine. This spine was commonly covered with a strip of silk fabric to help the binding stay intact, and with certain books (like Lafcadio Hearn’s boxed set), they are also capped at the top and bottom with silk. The front and back covers of the crepe-paper books are limp bound (meaning, there is no stiff backing material like cardboard).

In our collection alone, we do see see a couple of variations in technique, including two-hole and four-hole musubi-toji binding as well as a variation of hidden yotsume-toji binding with a silk piece of fabric glued onto the spine to mimic Western styles.

Click the button below to read about our experience learning Japanese binding techniques with Librarian Jillian Sparks.