Student Story

by Laura Smith '25

Learning Japanese Binding

Take one look at our collection of crepe-paper books. Alongside the paper’s texture and the vibrant cover illustrations, one of the first things you’ll notice is the colorful thread holding the pages together. The binding methods used in assembling these books were one of the first aspects we investigated in our research. The visible threads and knots are unlike the familiar glue and hidden-thread bindings of manufactured books today. You’ve already read about the technical details of Japanese binding for these books, but what is it like to actually put something like this together? One of the highlights of our summer was figuring this out with Jillian Sparks, our Distinctive Collections Engagement Librarian in Special Collections.

Rolvaag Memorial Library has a fantastic supply of materials for creative projects like this. We checked out a binding kit from DiSCO (Digital Scholarship Center), and the remaining supplies came from Special Collections, like the paper that was used at a previous bookbinding workshop for the exhibition “Behind the Spine.”

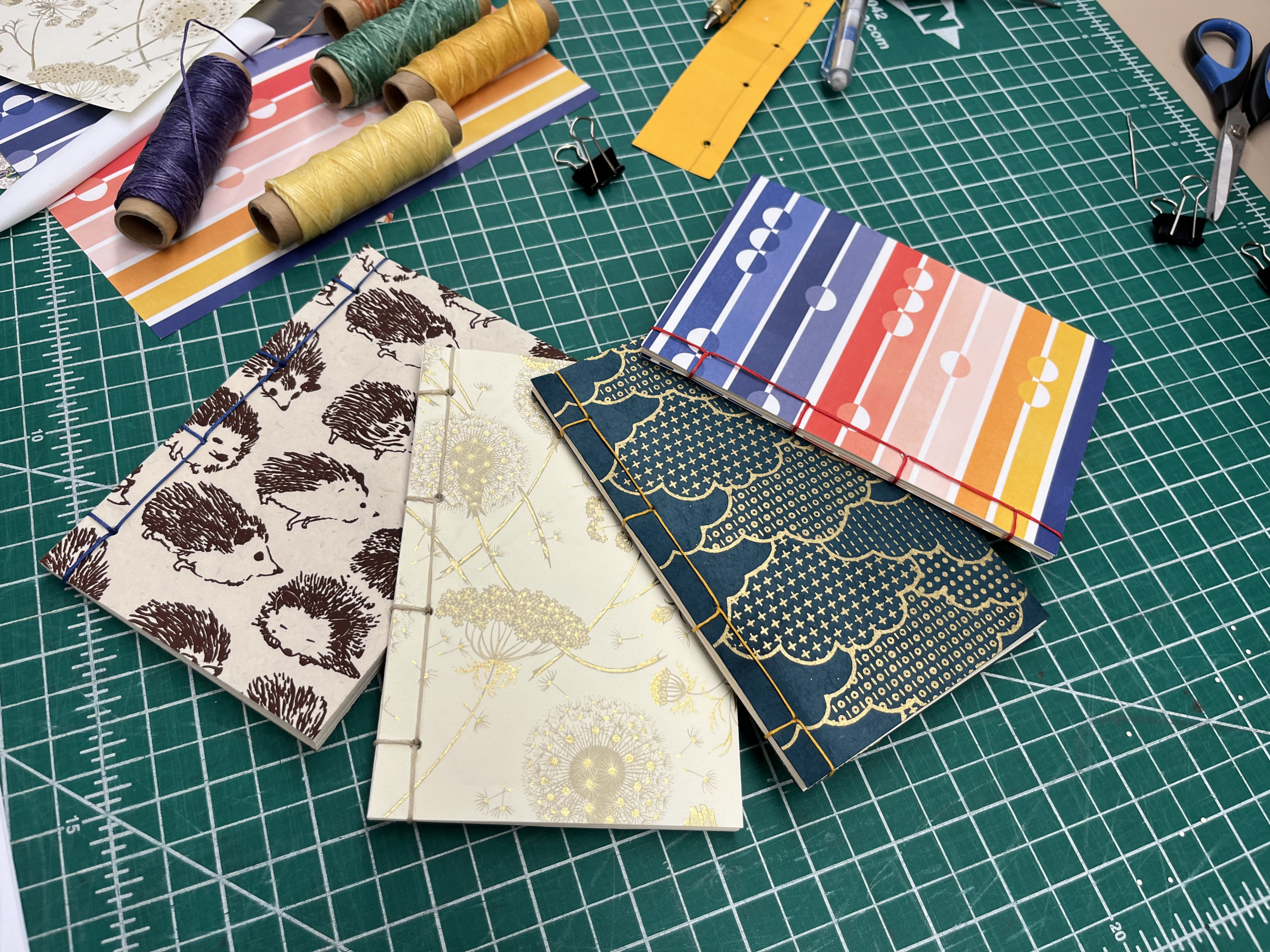

Excitedly gathered around a table in the Special Collections workspace, each of us chose pieces of decorative paper for the cover. (Something about cute stationary makes any process at least 10x more exciting)! Luckily, mass-manufactured pieces of printed paper are easily available nowadays. But at this point in the crepe-paper book publication process, the loose pages would have taken hours of labor from Hasegawa’s contracted workers—from the original illustration, to copying, carving, printing, creping, and cutting the paper.

For the actual pages of our books, we used cut sheets of paper from Special Collections. We arranged our pages in the same style of our crepe-paper books––folding the sheets in half, then aligning the open edges to the spine, leaving the folded edge on the outside. Historically, this method was useful for books containing woodblock prints, as the ink seeps through the paper. Because of this, the verso of printed pages are always left blank. Binding the pages this way meant blank spreads would not break up the text, and it strengthened the integrity of the pages.

We used 9 sheets of paper for our sample books to approximate the crepe-paper books in our collection. (Starting on the inside cover and counting each outward-facing side as a page, totaled to 20 pages, the same length of several of our books).

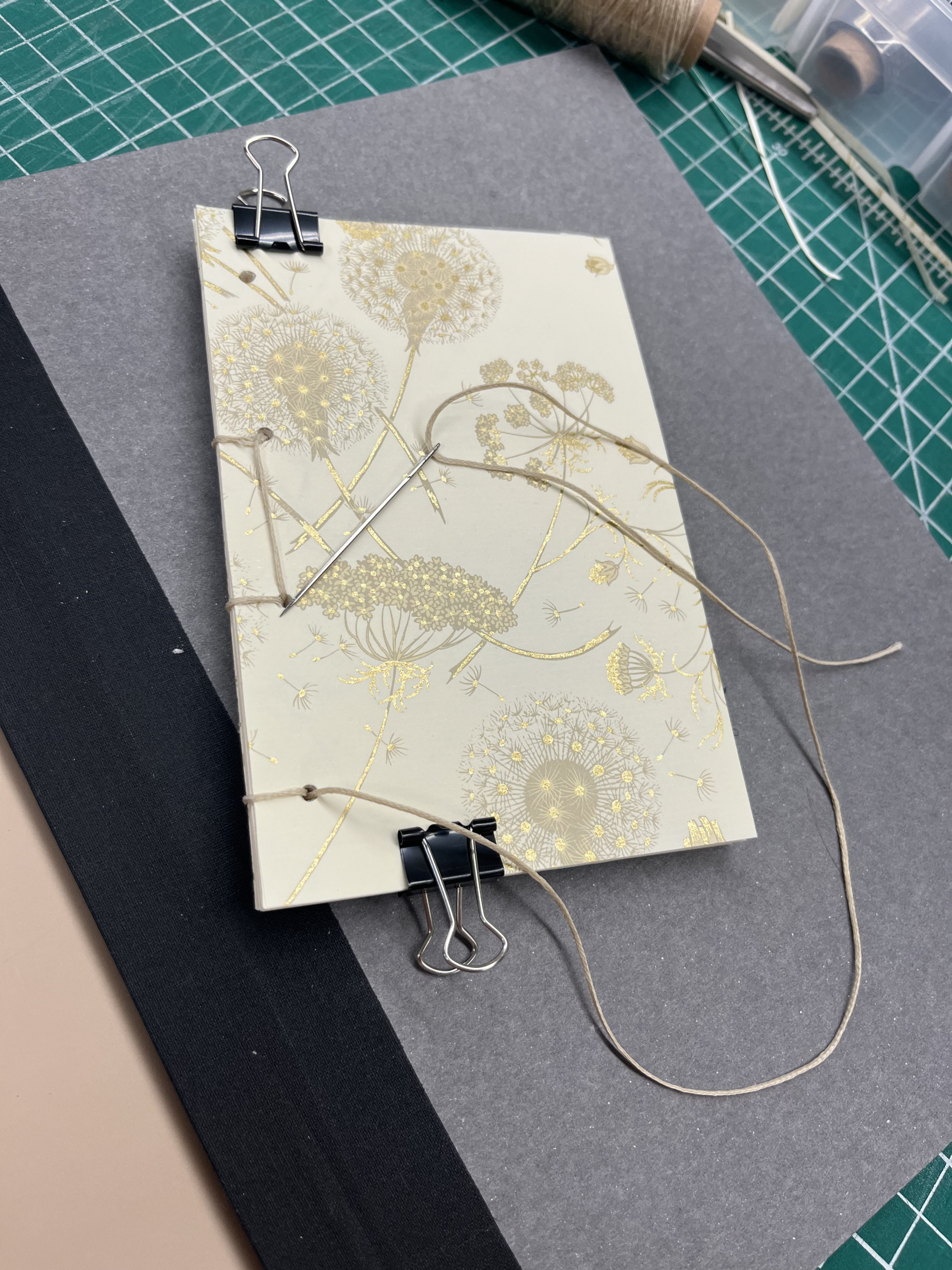

We bound these books in the yotsume-toji style with a 4-hole stab binding, following Jillian’s guidance and a YouTube video from artist Chang Yuchen. As the name states, the process involves stabbing four holes through the covers and pages, about a centimeter in from the spine. These holes can be stabbed with an awl, or they can be screw punched with a “push drill.”Then, threading the needle through the middle of the pages inside, we sewed out and across each hole, following Jillian’s step by step demonstration. The thread also extends over the top and bottom of the spine, capping the edges. The end result is a sturdy, neat, and aesthetically pleasing little notebook!

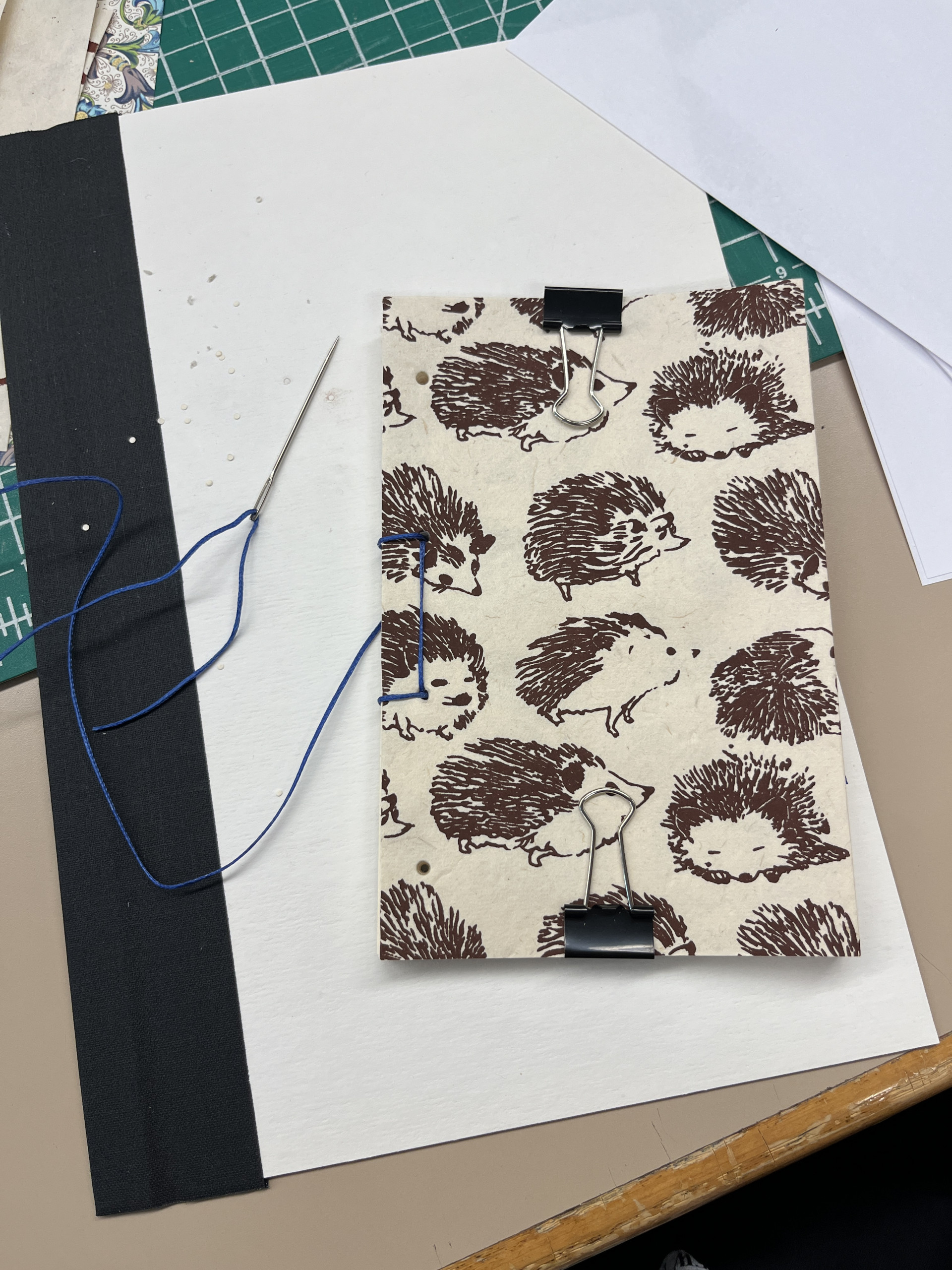

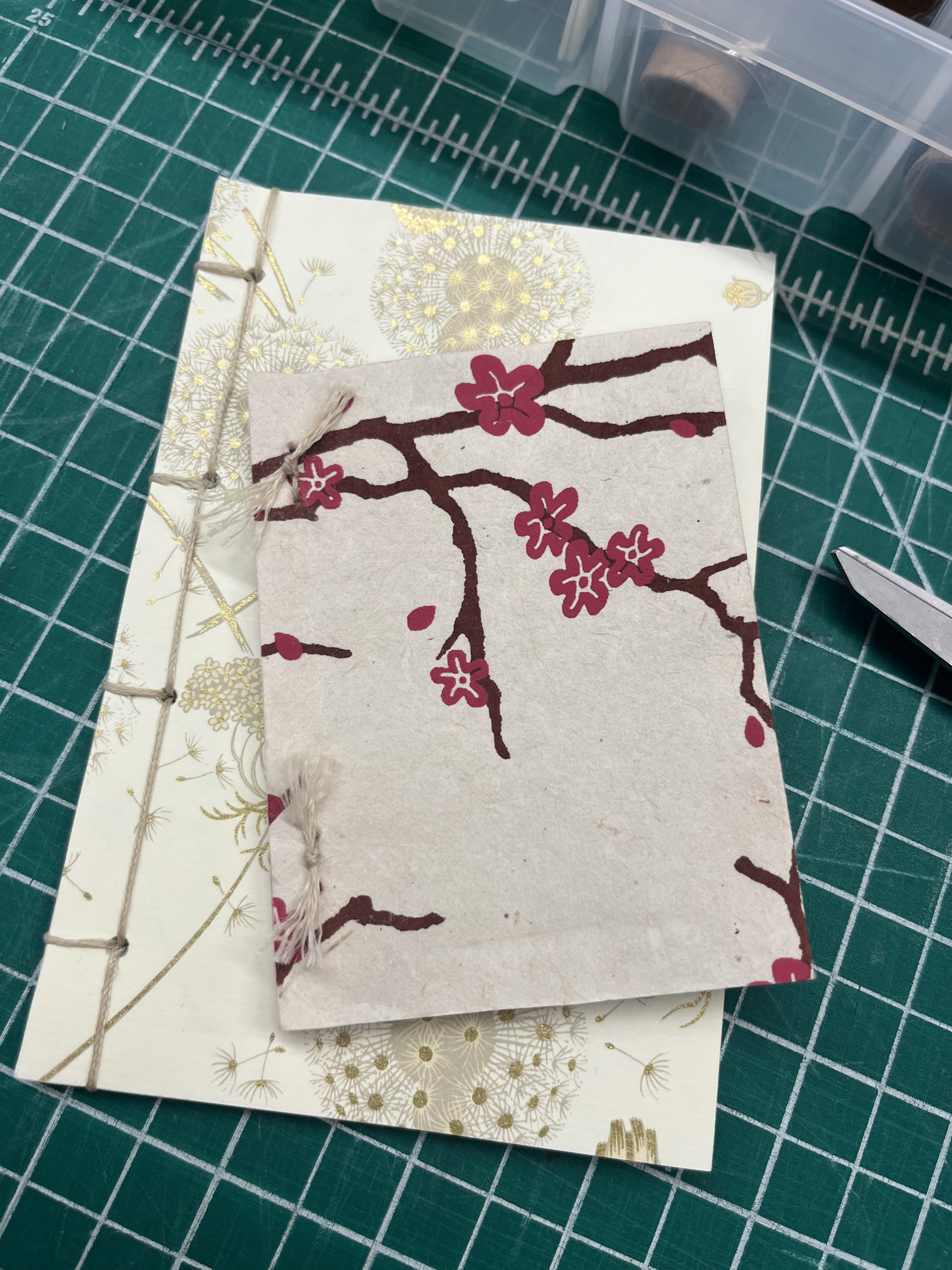

With time and extra supplies on our hands, we did a second round of books. Our second batch was smaller, and we used the 2-hole musubi-toji binding method, replicating the style of many of our books. Instead of evenly spacing the holes, we paired them close together towards either end of the book. We put the thread through one hole back through the other, and tied the ends together. We also pulled apart the loose thread of the knots to give a similar look to the multi-threaded knots of our books. Many of the fairy tales are bound in this way, or with the 4-hole variant, which is the same but with two added holes at either end for eight holes total, and the thread crosses itself on the back cover (see Hare of Inaba). We also did not cover the spines with extra material, although the historical process would have included the additional silk fabric.

So, at the end of the day, we were each two notebooks richer! By binding books, we also developed our understanding of the publication process. Researching historical art and publication processes can be difficult to truly comprehend. You can read the step-by-step explanations and memorize the technical details, but that does not necessarily convey the scope of effort required to produce something like a crepe-paper book. Experiments like these are enlightening. As beginners, they help us to understand the learning curve, the networking and connections it would take to acquire materials in a world without Amazon, the efficiency professional artisans would master with years of experience, and so on. Our experience with bookmaking was delightful and educational and looked much different from how Hasegawa’s publishing business would have operated. Even still, working with hands-on projects like this—or with Anika’s momidai—bettered our research. It strengthened our understanding of and inquiries into the process of making crepe-paper books by experiencing the physical labor involved and helped us develop empathy for the longer and more strenuous steps of historical methods. Ultimately, it granted us the ability to ask deeper, more informed questions.