Student Story

by Anika James '25

Creating the Momidai

The unique texture of the crepe-paper books was essential to the success of Hasegawa Takejirō’s publications. When we began our research into the technical process involved in creating the books, it quickly became clear that it would take a hands-on approach for us to understand what it was like to manufacture crepe paper. Hasegawa was not the sole producer of crepe products, but he was certainly the most successful at it, and he kept his manufacturing details relatively secret. However, we were able to locate one resource detailing the process by Johann Justus Rein, in The Industries of Japan. Published in 1889, this account was part of an attempt by the Prussian government to document various industries in Japan comprehensively. It is unlikely that Rein and his colleagues had been observing Hasegawa’s studio, but this was the best information that we had to work with.

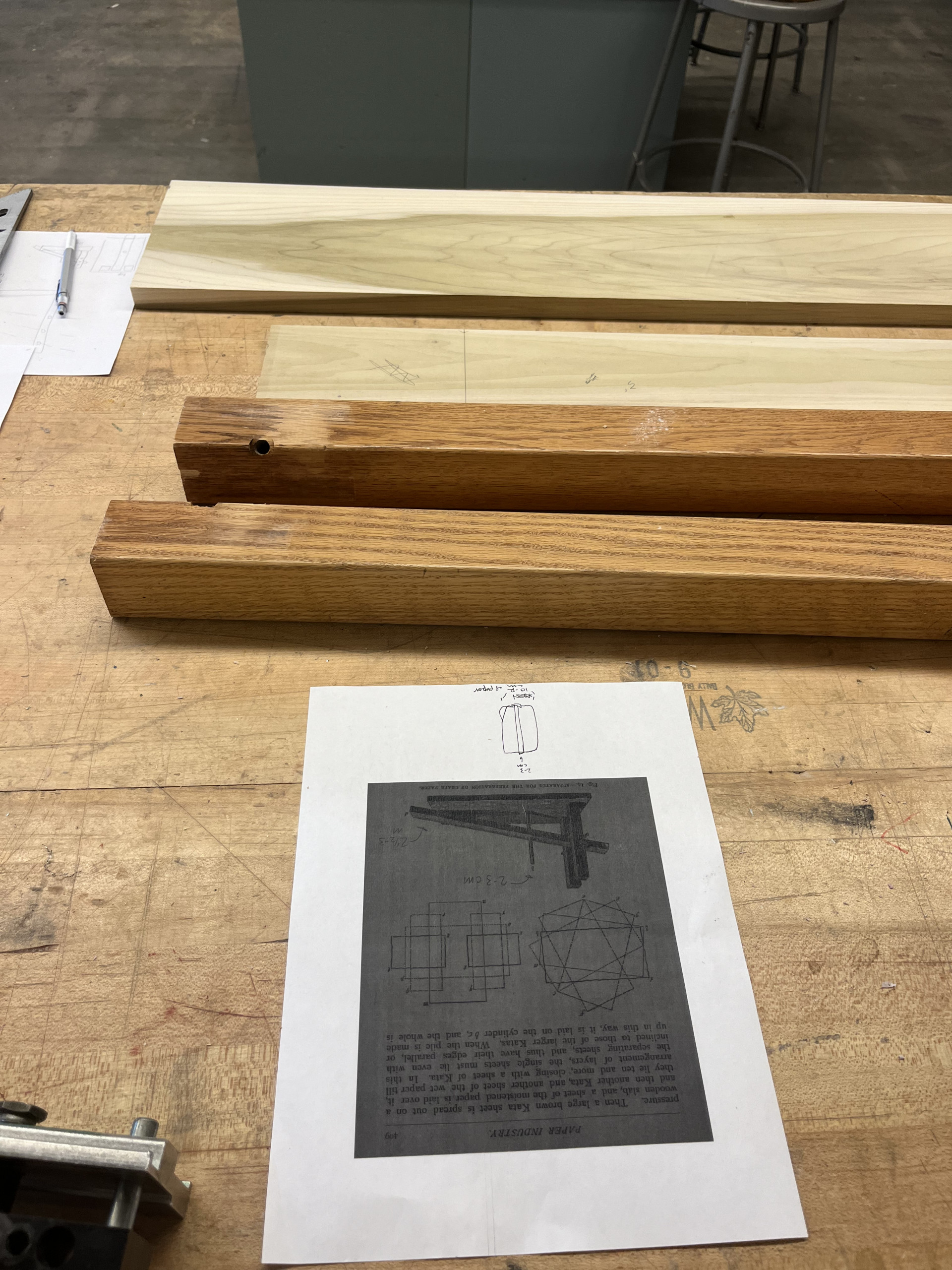

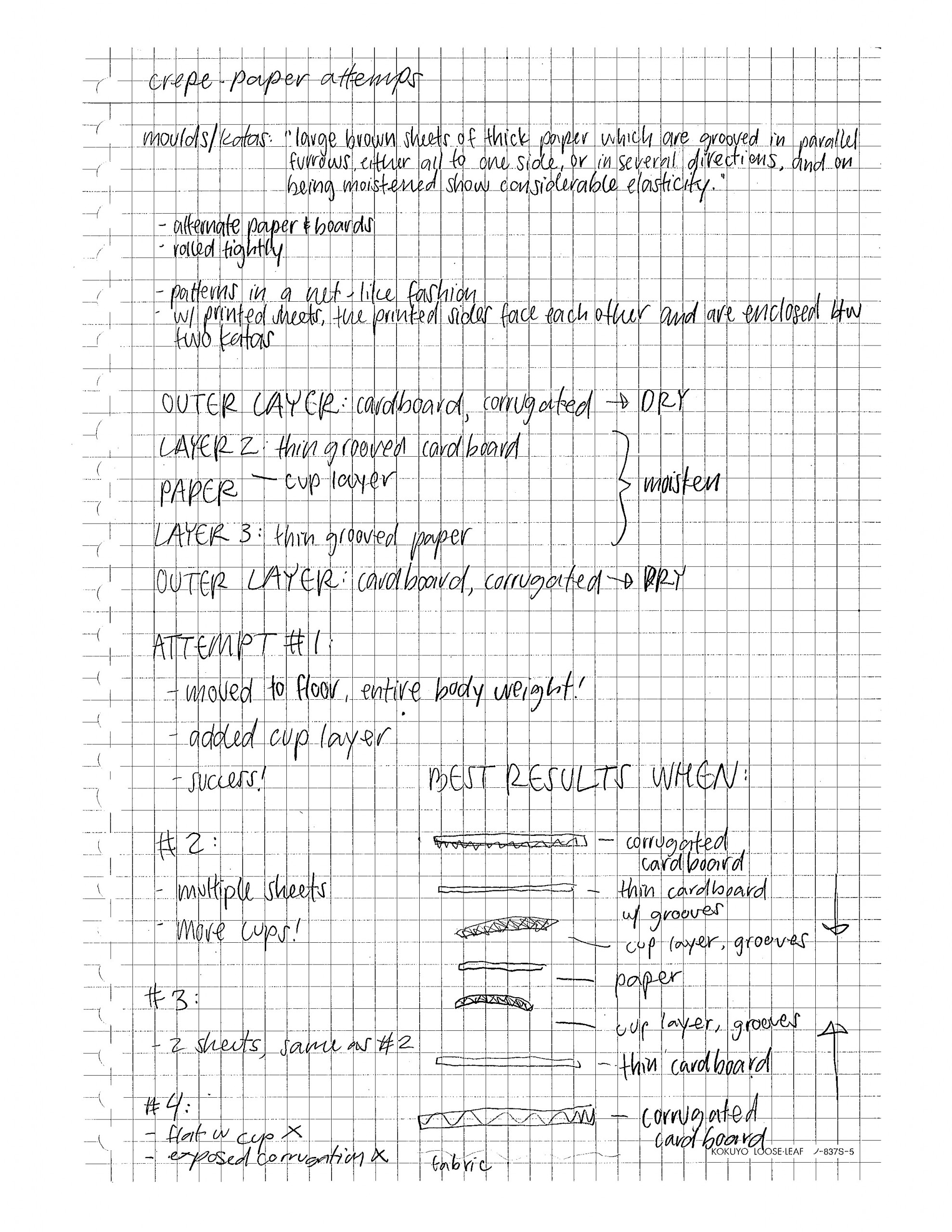

I began making some sketches and mock-ups of the momidai before heading to the Center of Art and Dance woodshop, where Studio Technician Anders Nienstaedt helped source materials and give feedback. I found two sturdy oak chair legs that were the exact height we wanted and already had holes drilled into them that we could use to hold the main board in place. After deliberating about the scale and creating some sample pieces, I began the process of cutting, sanding, and drilling pieces together. It was a long process of trial and error, and we were not sure how it would work until finishing and testing.

One of the final steps in assembling the momidai was to create a shallow groove for the central rod to rest in. To do this, I used a gouge to carve out a groove about an inch in diameter on a separate board that rested on the base. Gouges come in various sizes and are also used in woodblock printing, and I quickly realized how much precision and patience it would take to use this tool for such delicate work. After I finished carving, I sanded everything down and made the final attachments, screwing the legs into the base. The base and the central rod were removable, allowing us to change the size of the rod if needed.

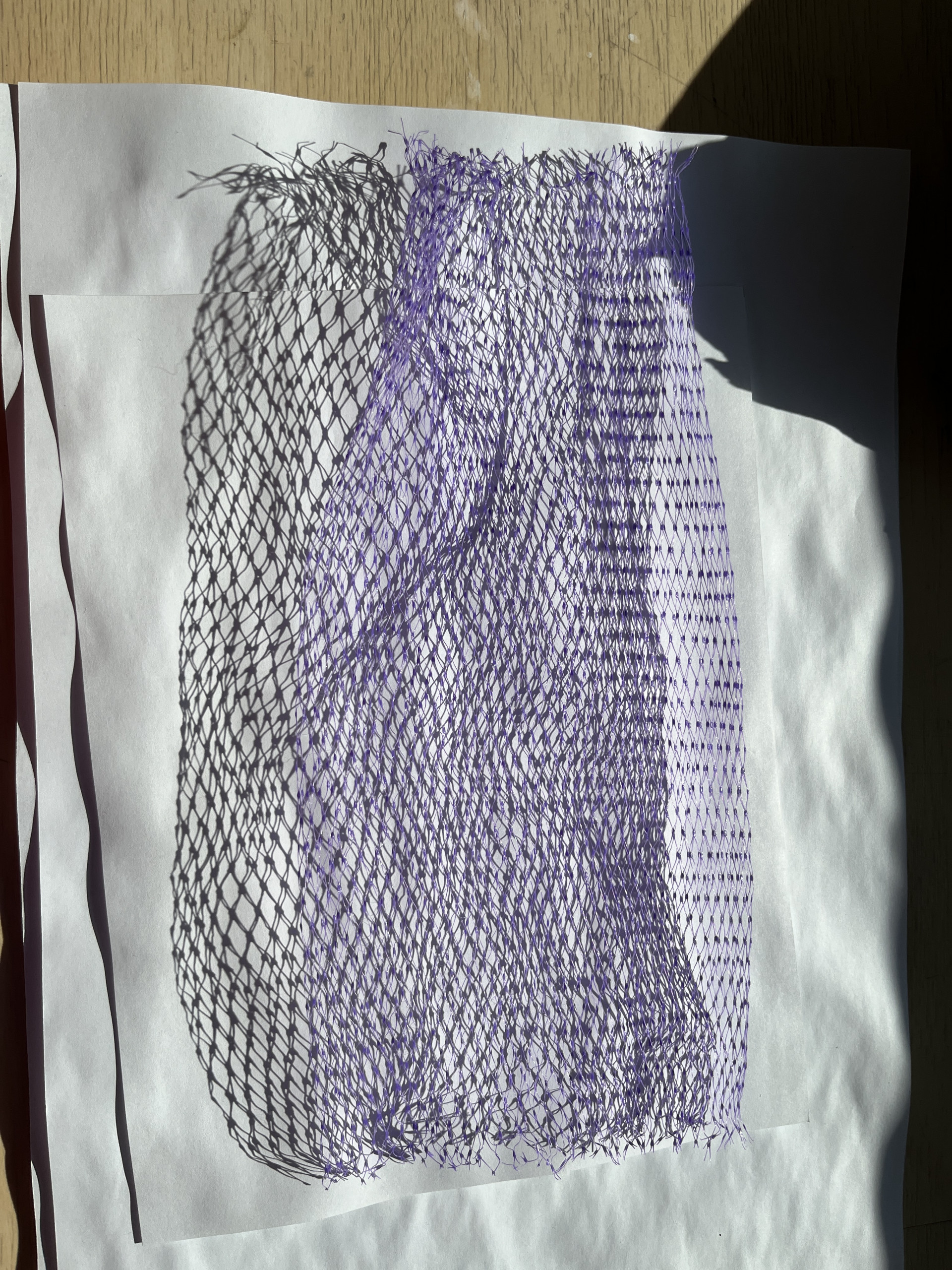

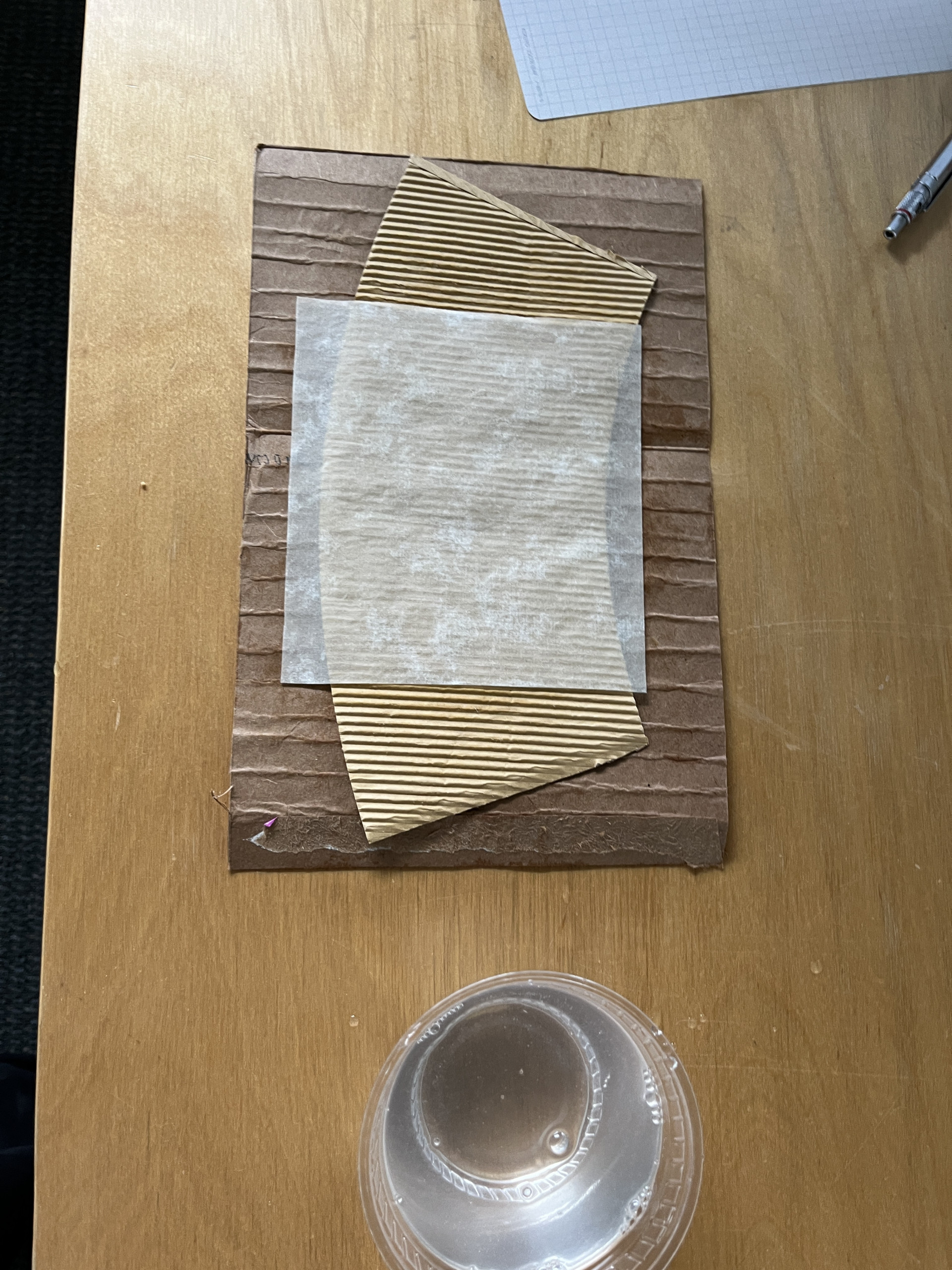

Our next step was to figure out how to actually use our momidai. We chose various materials to experiment with, from corrugated cardboard to textured coffee cup sleeves to plastic netting. In our first attempts, we used thin cardboard that had been folded every centimeter to create a grooved effect. However, we realized that these “forms” did not leave a very strong imprint, and decided to start adding more textured materials. We were delighted and quite surprised that the momidai worked, and were impressed with the weight that it was able to withstand. To operate it, we would take our materials wrapped around the rod, put it into position, and have one person hold the legs down, and the other sit with their entire body weight on the opposite end of the lever.

We experimented with our process over two days, and on the second day, we tried putting our mulberry paper through the printer to see how it would hold up during crepeing. It held up best when we did not wet the paper, as it helped keep the ink in place. Overall, this was just the beginning of recreating creped paper. Because we relied so much on cardboard to secure our papers, it began to deteriorate quickly as we had to continue putting pressure and moisture on each piece. In recreating crepe paper, we were able to gain a better understanding of how the unique texture was created, as well as a deep appreciation for the intensive labor that went into each book.