“The struggles Congolese women face today are rooted in a long history of oppression, dating back to slavery. To advocate effectively, we must understand the history of Congo and how it shaped the challenges women endure in Congo today”

Sarah Balekage

Part 1: Geography

“Democratic Republic of the Congo, 2025

The Democratic Republic of Congo is a country located in Sub-Saharan Africa, precisely in central Africa. It is the second largest country in Africa following Algeria occupying 905,355 sq mi, and the 11th largest country in the world.

Demography & Language

Home to over 115 million people, the DRC is the most populous French-speaking country in the world. About 51% of the population are women, and nearly 48% are under the age of 15. While French is the official language, the country is rich in linguistic diversity, with around 200 local languages spoken.

Capital and major cities

The capital, Kinshasa, is Congo’s political, economic, and cultural center with over 17 million people. Other major cities include:

- Lubumbashi: the mining capital in the south.

- Goma: a key eastern city on Lake Kivu, near Virunga National Park.

- Bukavu: known for its hills, activism, and lakeside beauty.

- Kananga : an important agricultural and trade hub.

- Mbuji-Mayi: famous for diamond mining.

Culture and Food

The DRC boasts a vibrant and diverse culture rooted in its ethnic variety and history. Traditional music and dance, including rumba congolaise and ndombolo, are central to social life. Congolese cuisine is rich and hearty, featuring staple dishes like fufu (a dough-like side made from cassava or maize), pondu (cassava leaves stew), moambe chicken, and fresh river fish. Food and community gatherings play a big part in everyday life, reflecting the warmth and resilience of the Congolese people.

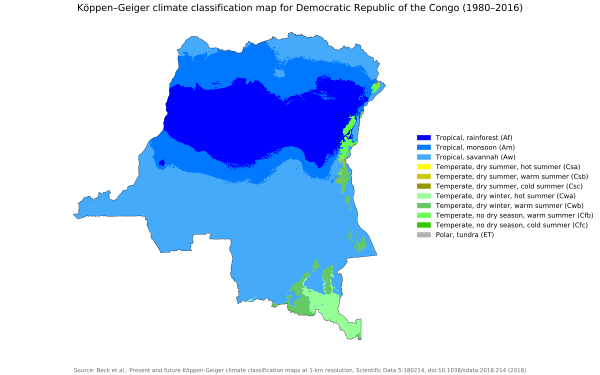

Relief of the DRC

The relief of the Congo region is characterized by a vast, low-lying central basin, a coastal plain and mountain areas on the East and West of the country. The climate of Congo ranges from the tropical rainforest in the basin of the Congo river to tropical wet and dry in the southern part to tropical highlands in the eastern part of the country

(Geography of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, 2025)

Part 2: History

“As long as the oppressed remain unaware of the causes of their condition, they fatalistically ‘accept their exploitation.” – Paulo Freire

Early Migrations and the Role of Women

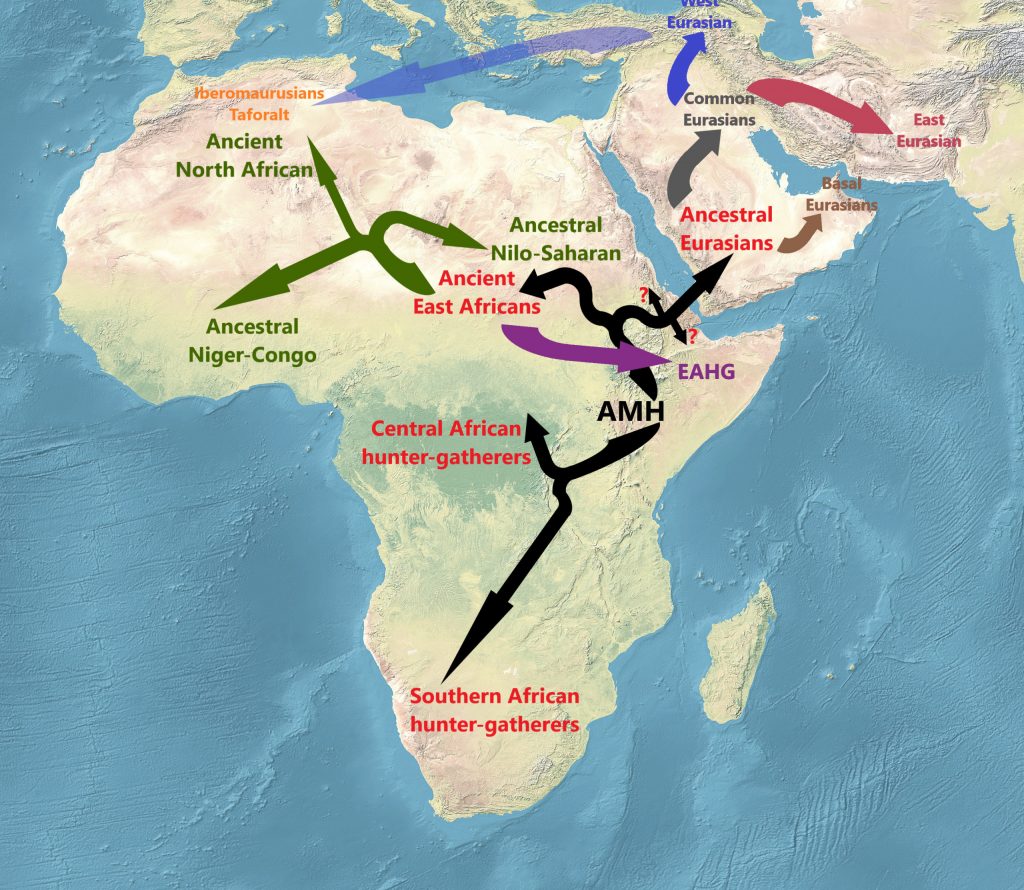

Congo’s history stretches back over 90,000 years, first inhabited by African Pygmies. Around 13,000 years ago, the Sahara began to dry up, forcing Bantu-speaking communities to migrate across Africa. Many settled in the Congo Basin, displacing indigenous Pygmies in search of water and fertile land (Oxford Research Encyclopedias).

During this migration, women played a central role in community survival. They were responsible for farming, raising children, crafting, and preserving cultural traditions — laying the foundations for future generations.

Formation of Kingdoms and Women’s Contributions

By the 13th century, several powerful kingdoms, including Kongo, Pemba, and Ngoyo, emerged in the Congo Basin. War captives became enslaved laborers to support these expanding states (Nzongola-Ntalaja, 2002).

Even in male-dominated societies, women held influence in politics, trade, religion, and culture. Elite women could mediate disputes, advise kings, and lead religious movements, like Don Beatriz, who led the Antonian movement (Thornton, 2006).

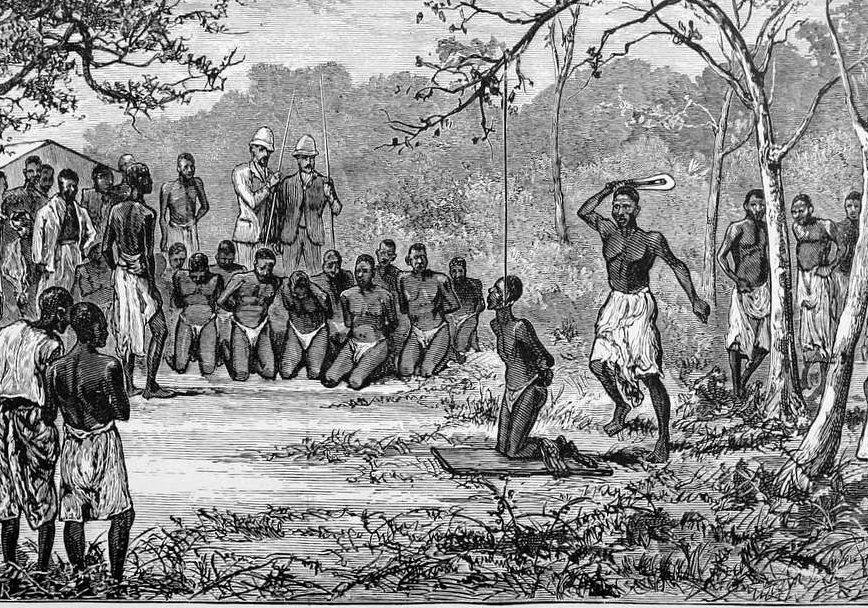

The Slave Trade and Its Impact on Women

Slavery existed within these kingdoms long before European contact. When the Portuguese arrived in 1482, they began trading goods and weapons in exchange for enslaved people. Women made up about one-third of those taken in the transatlantic slave trade (Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History).

Enslaved women faced brutal conditions — forced into fieldwork, domestic labor, and subjected to exploitation (Gilder Lehrman Institute). Despite this, they preserved cultural traditions, resisted oppression, and maintained family networks within enslaved communities.

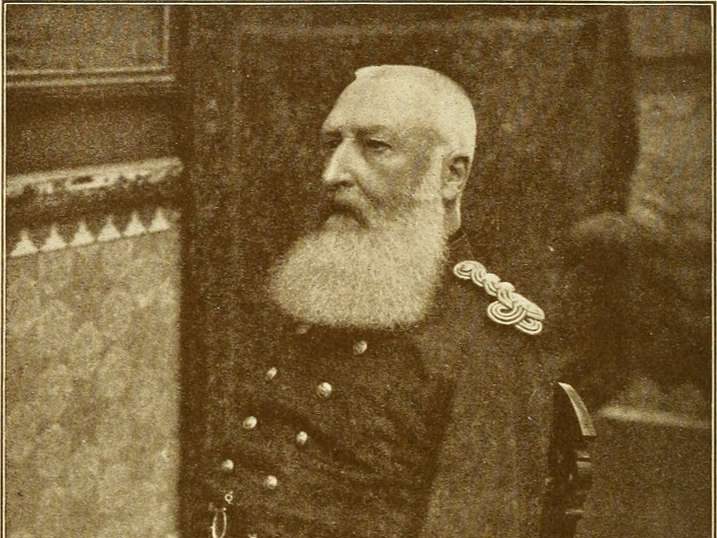

The Formation of Congo

In the late 1800s, as European powers competed for control of Africa, Congo was divided during the Berlin Conference of 1884-1885. Parts of the Kongo kingdom were split between France and Belgium, separating families and communities. That is the reason why there is Republic of Congo and Democratic Republic of Congo (Nzongola-Ntalaja, 2002).

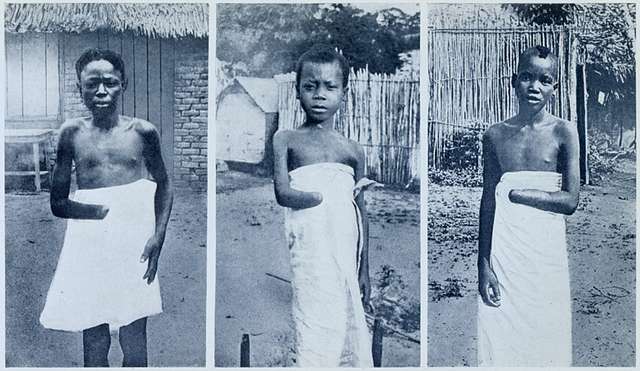

King Leopold II of Belgium claimed the Congo Free State as his personal property, exploiting its vast natural resources and people. His brutal regime killed over 10 million Congolese through violence, forced labor, and disease. Women were forced into hard labor, faced family separation, and lost their traditional social and political roles (Zapata, 2011).

Colonial Rule (1908-1960)

In 1908, after international pressure, the Belgian government took control, renaming it Belgian Congo. Colonizers imposed Belgian language, culture, and harsh labor policies. Congolese women were often excluded from education, pushed into domestic roles, and denied land ownership. Yet, many showed resilience — forming support groups and preserving cultural identity (Nzongola-Ntalaja, 2002).

During World War II, Congolese soldiers, including Force Publique, fought for Belgium. Congo’s resource wealth made it the richest African colony by the 1950s, but its people, especially women, continued to endure poverty, repression, and racism (Lauro, 2020).

Women and the Fight for Independence

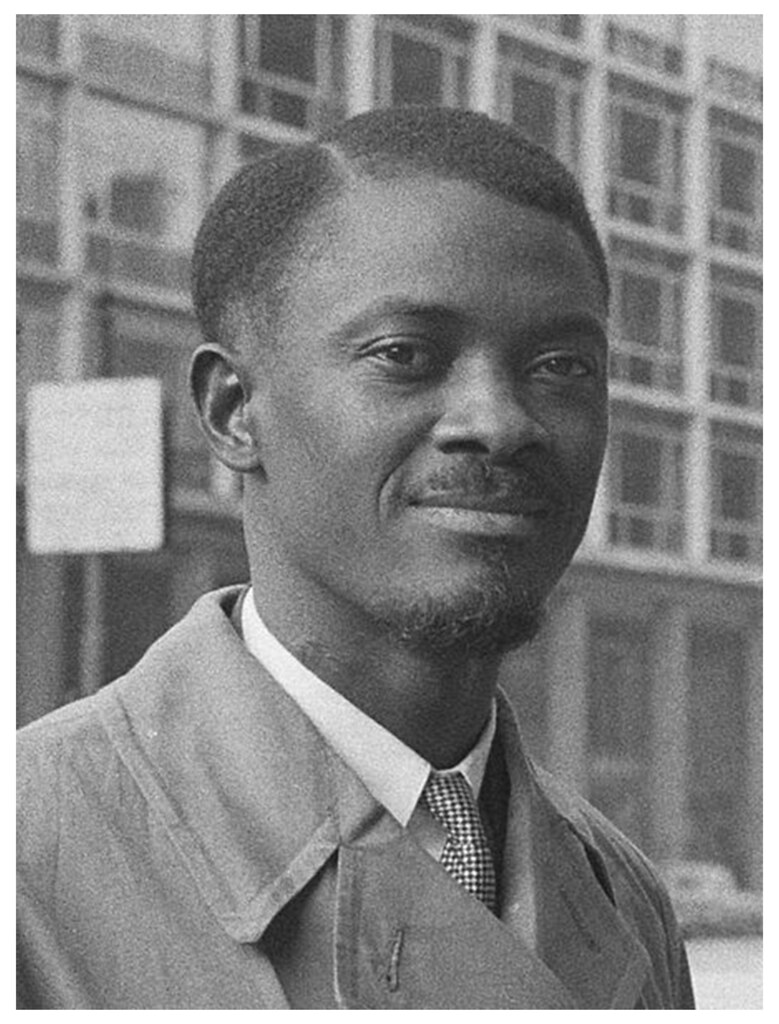

Despite restrictions, Congolese women actively resisted colonial oppression. They organized protests, joined political movements, and built underground networks to fight for freedom. Limited to minor jobs and denied higher education, many women demanded change through grassroots activism and solidarity groups. Andree Blouin was a politician and activist from Central African Republic who alongside Patrice Emery Lumumba, used her plateform to advocate and mobilise women in Congo to stand agaisnt Colonisation (Andrée Blouin – Africa’s Overlooked Independence Heroine, 2025).

The push for independence intensified with protests in 1959, leading to Congo’s liberation from Belgian rule on June 30, 1960.

The Congo Crisis and Its Aftermath (1960-1965)

After independence, Congo faced political chaos. Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba and President Joseph Kasa-Vubu clashed as the army mutinied and provinces tried to secede. Over 10,000 people died, including Lumumba, in what became known as the Congo (Crisis Nzongola-Ntalaja, 2002).

Amid violence and instability, women suffered increased displacement, violence, and loss of family members. Though many continued to protest, serve as caregivers, and hold communities together, their suffering was largely overlooked in official records.

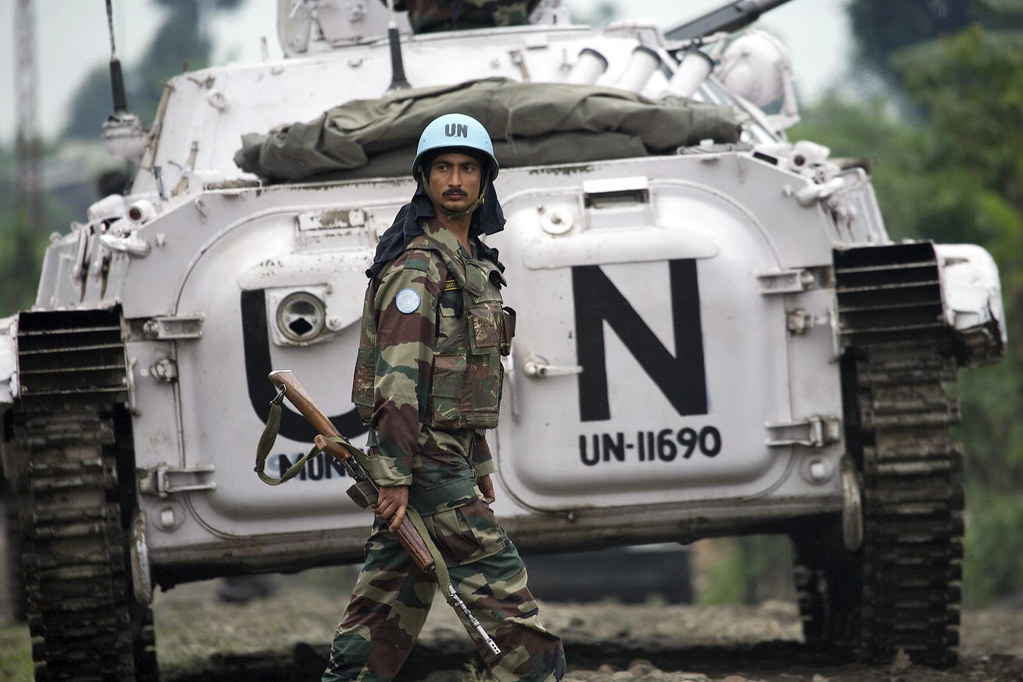

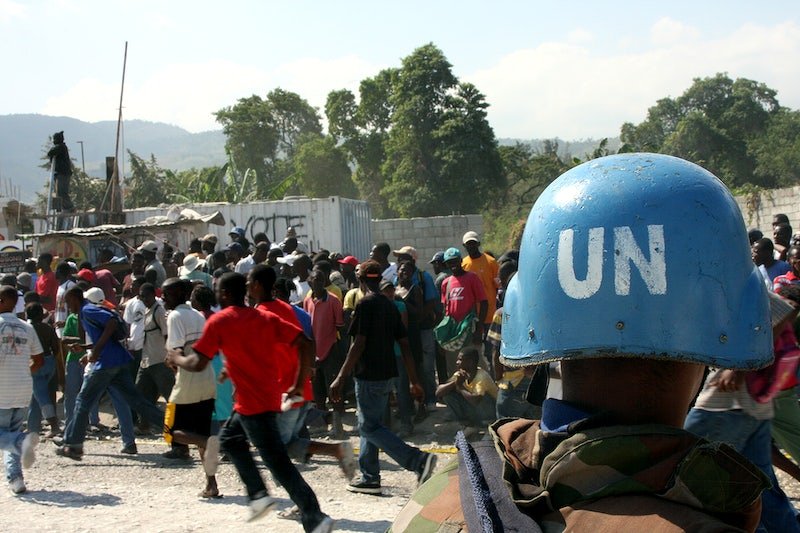

The crisis prompted the creation of ONUC, a United Nations peacekeeping mission, but the country remained unstable for years (United Nations Peacekeeping Archives).

Mobutu’s Dictatorship and Its Impact on Women

After Congo gained independence in 1960, political instability spread quickly. Colonel Joseph Mobutu staged a coup, later taking full power in 1965 (Bailey, n.d.). Mobutu established a harsh dictatorship, banning political parties, controlling the media, and brutally silencing opponents. He renamed the country Zaire and imposed strict policies aimed at erasing colonial influences — even forcing citizens to abandon European names.

While Mobutu’s early reign promised peace, it quickly turned into a kleptocracy. He and his inner circle seized national resources, plunging most of the population into poverty. By 1993, over 1.8 million people suffered from malnutrition, and healthcare and education systems collapsed (Bailey, n.d.).

Women bore the heaviest burdens during this time. As the country’s economy crumbled, women took on the responsibility of feeding their families, often turning to informal markets, farming, and cross-border trade. Yet, these roles exposed them to constant harassment, exploitation, and arbitrary arrests by security forces (Bailey, n.d.). Political repression also impacted women’s rights activists and female leaders, many of whom were silenced, exiled, or executed.

In 1990, when students protested against Mobutu’s regime, 150 were killed — a tragedy that particularly devastated young women in academic spaces who were already marginalized (Bailey, n.d.)

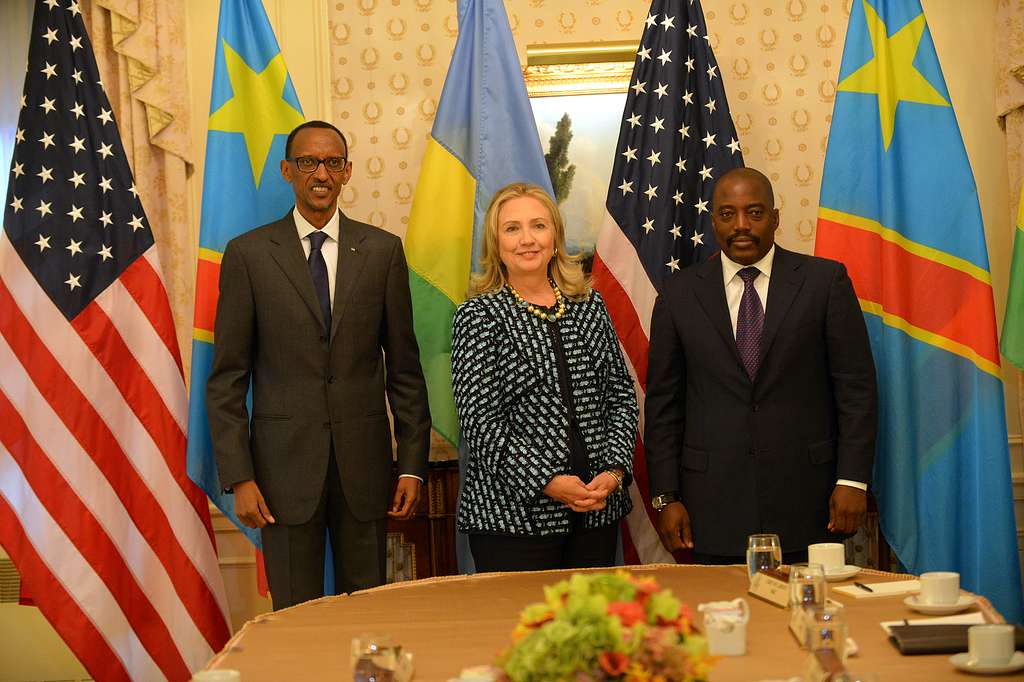

Meanwhile, In 1994, neighboring Rwanda experienced one of the most horrific genocides in modern history, with over 800,000 Tutsi and moderate Hutu killed within 100 days (Des Forges, 1999). Following the genocide, around 2 million Hutu refugees — including genocidal militias (Interahamwe) fled into eastern Congo (then Zaire), bringing weapons, conflict, and instability into the region (Prunier, 2009).

These armed groups used refugee camps as bases for attacks into Rwanda and against local Congolese communities, contributing to the eruption of the First Congo War (1996–1997). Rwandan and Ugandan forces allied with Congolese rebels led by Laurent Desire Kabila to overthrow Mobutu, who fled in 1997, ending his dictatorship. The country was renamed the Democratic Republic of Congo and Laurent Desire Kabila became President (DRC) (Stearns, 2011).

Congolese crisis and its impact on women

After removing Mobutu in 1997, Laurent Kabila became president of Zaire and renamed it the Democratic Republic of Congo. He distanced himself from Rwanda, removed Tutsis from government, and expelled foreign troops, allowing Hutu armed groups to reorganize. This move triggered a multi-state war involving Angola, Namibia, and Zimbabwe supporting Congo, while Rwanda, Uganda, and Burundi backed rebel groups. The conflict, known as the Second Congo War, claimed over 5.4 million lives — the deadliest since World War II — and led to the creation of MONUC, a UN peacekeeping mission (Bailey, n.d.; Monuc Mandate – United Nations Organization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, n.d.).

In 2001, Laurent Kabila was assassinated by his bodyguard. His son, Joseph Kabila, took power and led peace talks between 2002–2003. Despite a new government and UN interventions, violence continued in eastern Congo. In 2006, the country held its first democratic elections in decades, confirming Joseph Kabila as president.

However, in the early 2000s, a rebel group called M23, mainly made up of ethnic Tutsi fighters, emerged in eastern Congo. Supported by Rwanda, M23 became a major threat between 2012–2013. The UN responded by creating MONUSCO to replace MONUC, deploying an offensive brigade to defeat M23 (MONUSCO Ending Its Mission in South Kivu, 2024). Though temporarily subdued, tensions between Congo and Rwanda deepened (Monuc Mandate, n.d.). This mission was later succeeded by the United Nations Organization Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (MONUSCO) in 2010, aiming to protect civilians and consolidate peace in the region .United Nations Peacekeeping

In 2018, Félix Tshisekedi was declared president, marking Congo’s first peaceful transfer of power since independence. However, the election’s fairness was disputed, with independent polls suggesting rival candidate Martin Fayulu may have won (Bailey, n.d.).

After taking office in 2019, President Félix Tshisekedi faced serious challenges: recurring Ebola outbreaks, widespread violence, and instability in eastern Congo, a region long troubled by local grievances and the global demand for minerals like cobalt, coltan, and gold. The exploitation of these resources fueled conflicts and drew foreign interests.

In 2022, the rebel group M23 resurfaced after years of silence, capturing large areas of North Kivu by mid-2023. The Congolese government accused Rwanda of backing M23, while Rwanda blamed Congo for supporting Hutu militias like the FDLR. Both sides maintained military forces along the border, with Rwandan and Ugandan interests tied to the region’s valuable mines.

By late 2023, tensions escalated. The UN warned of the risk of open war between Congo and Rwanda. The U.S. brokered a temporary agreement for ceasefire and military de-escalation, but violence continued into 2024. Public anger grew against the UN peacekeeping mission, MONUSCO, for failing to protect civilians, leading Tshisekedi to call for its withdrawal by the end of 2023. However, fearing a security vacuum, the UN extended MONUSCO’s mandate through 2024.

As violence spread through Congo’s eastern provinces, Women and girls were systematically targeted, with widespread rape, sexual slavery, and torture used as weapons of war (UN Mapping Report, 2010). Survivors also faced severe stigma and trauma, often rejected by their communities. According to Human Right Watch, most women were forcibly displaced, conscripted into militias, and made to carry heavy loads for armed groups (Human Rights Watch, 2002). Finally, the collapse of infrastructure and healthcare severely affected maternal health and safety in conflict zones (Bartels et al., 2010).

Most recent crisis

In early 2025, M23, with the support of rebel groups and disaffected politicians like Corneille Nangaa, launched a major offensive. They captured Goma, its international airport, killed the North Kivu governor, and took control of all South Kivu — including my hometown Bukavu.