Wickedness & Evil Conference paper

Hoping for Heaven, Landing in Hell:

Lessons Learned at a Medieval Chinese Grotto

By Karil Kucera, St. Olaf College

The mention of Buddhist hells inevitably elicits surprise. Modern Western understandings of Buddhism rarely incorporate what is thought to be a more Christian concept, a punitive approach to keeping people on the appropriate path. Yet belief in Buddhist hells and the retribution they rained down upon the sinner was strong in the Chinese medieval period. So strong, in fact, that numerous illustrated works were produced to aid in the dissemination of this idea. A series of monumental sculptural works related to hell from this period can still be seen today at the Buddhist site of Baodingshan.

Baodingshan consists of a monastic complex and two grotto areas, Little Buddha Bend (Xiaofowan) and Great Buddha Bend (Dafowan) [fig. 1]. Located on a remote, rocky outcropping at an elevation of approximately 500 meters, fifteen kilometers north of Dazu City in Sichuan Province, Baodingshan, was an active religious site into at least the late Ming dynasty (1368-1644 CE) with primary construction at the site dating from the Southern Song period (1127-1270 CE).[1]

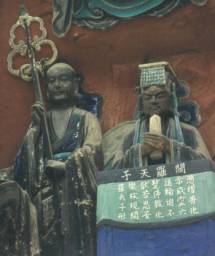

Fig. 1 Overview of Baodingshan complex, Dazu, Sichuan, China

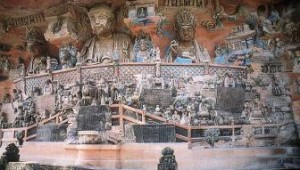

This paper focuses on two of the large tableaux located on the far end of the north side of Great Buddha Bend, the relief depicting the Pure Land or “heaven” and the relief depicting Dizang Bodhisattva , the ten kings of hell, and the eighteen hells that they oversee [figs. 2 and 3]. There is an inherent logic to considering these two works as a pair, the most obvious being the ritual context surrounding attempts to alleviate the suffering of the deceased by appeasing the Ten Kings of Hell, thereby speeding them onto rebirth in the heavens of the Pure Land.

Fig. 2 The Pure Land at Baodingshan

Fig. 3 Dizang Bodhisattva, the Ten Kings, and the 18 Hells at Baodingshan

HOPING FOR HEAVEN

The images that confront the worshipper in the tableau depicting the heavens of the Pure Land cover an area of approximately 160 square meters and are for the most part iconic. [2] Three large sculptures of the Buddha Amitayus flanked by two bodhisattva figures loom over the faithful, all three equally awe-inspiring in scale.[3]To Amitayus’ right is Avalokitesvara, her bejeweled crown bearing the identifying small Amitabha figure. Guanyin, as Avalokitesvara is known in China, carries here a flywhisk in her right hand, a bowl cradled in her left palm. This is in keeping with the iconography of the bowl as representative of the Buddhist Law with the flywhisk highlighting Guanyin’s compassion toward all living creatures. To Amitayus’ left is Mahastamaprapta, who is also depicted resplendently, left hand extended palm up. Rising above them and scattered throughout the tableau are the palaces of the Pure Land paradise peopled with heavenly beings.

Although the central icons are meant to focus the worshipper, what draws the eye are the multiple small figures in various states of rebirth: some popping out of lotuses, others holding up their hands in reverence, still others crawling along the balustrade, all young at heart in their new life in the Pure Land [fig. 4]. These newborn souls demonstrate how the layperson can be reborn into paradise.

Fig. 4 Newborn Soul emerging from lotus blossom in the Pure Land

LANDING IN HELL

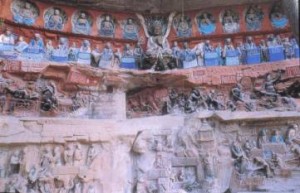

If the heavens appear pleasant, palatial and welcoming then the nearby hells were clearly intended to frighten and overwhelm the viewer [fig. 5]. From the images of rebirth in the Pure Land, one proceeds physically downward to view the hell tableau. The disoriented viewer is thus himself or herself placed in the very bowels of hell, face to face with the eternally damned. There are 18 hells described and represented at Baodingshan as well as four admonitions. All are discrete units linked by a common theme -bad deeds lead to bad places! Hell is replete with gendered anonymous people, thereby making it all-inclusive.

Fig. 5 Hell at Baodingshan from a worshippers point of view

Di yu or ‘earth-prison’ is the Chinese term for hell. Prison is an interesting metaphor for hell, and one first used by the Chinese. Links to the real world were fundamental to hell imagery. The penal ideology of the day reflected a combination of rewards and punishments that served as effective means for changing behavior. Such was the case within Buddhist ideology as well; an individual was not damned for all eternity, but upon repaying his karmic mistakes, would automatically be freed into a new existence, capable of starting anew. Like the Song dynasty penal codes, however, one did not pass from a state of guilt to one of innocence without paying a price. Payment involving rituals being performed to release the dead from the various hells easily correlate with real-life bribes paid to jailers at regular intervals in order to ensure the jailed individual’s wellbeing and hoped-for eventual release.

The jailers at Great Buddha Bend can be seen as an example of art imitating life [fig. 6]. During the Song dynasty, the military became increasingly involved in executions and punishment, with many soldiers making their living by forcing inmates to pay them for leniency or freedom. It is not then surprising that at Baodingshan these purveyors of punishment should wear cuirasses, boots, and helmets. The fact that many of the soldiers were also themselves convicts, forced into conscription in order to serve out their sentence, is another aspect to be considered with regard to the pleasure these individuals seem to derive from causing pain as shown in the Baodingshan imagery. Furthermore, many of the jailers depicted within the hell scenes are grotesque, reflecting Chinese penal policy of scarring or mutilating interred criminals, many of which in turn would become jailers. It is important to note the difference in scale that becomes apparent within the hells. The jailers in these scenes clearly dominate the damned within the hell regions. They are tall and brawny, helping to emphasize the shirking, insignificant souls at their feet.

In yet another instance of art paralleling life, the torturous cangue appears on four different individuals scattered throughout the two levels of hell in the tableau, and were perhaps the most visible form of punishment in Song China [fig. 7]. Cangues were used to transport criminals, to torture innocent individuals in order to gain information, and to publicly humiliate the incarcerated.[4]

In China, visual images of hell far exceeded literary descriptions of hell in both their variety and their detail; the hells at Baodingshan number eighteen in all, and they do not appear to follow any one specific Buddhist text. Since time is limited, I will not show you all of the 18 hells, but rather a selection from the various levels of the hells.

The first hell to greet the worshipper at Baodingshan is not a hell at all. It is simply an admonition to better behaviour. Seated squarely in front of the worshipper is a figure that arguably could be seen as one of hell’s most-suffering inhabitants. One of only two female figures depicted at Great Buddha Bend with her breasts uncovered, this mournful creature sits at ground level, her mouth open, feet planted, hands clutched into tight fists placed in her lap [fig. 8]. This image represents a soul utterly humiliated, and one is left to wonder what wickedness she must have committed to suffer such a fate. As Chinese custom at the time called for entire coverage of the body with the exception of hands and face, in the real world, only individuals who were being punished would be subjected to forced public nakedness. Thus the nakedness of the damned added an extra dimension of horror for the worshipper.

The likely source for this image’s suffering is found in the inscription accompanying the Admonition against Alcohol:

A person such as the girl who buys and sells alcohol, will die and fall into hell. When receipt of her punishment is concluded, she will be (reborn with) a body three feet high, two ears blocked shut, a face without two eyes, likewise without nostrils, underneath the lips, a gaping mouth, hands without ten fingers, legs without two feet.[5]

A close examination of the carved image shows that her mouth is not open per se but lipless, a gaping hole. Her hands are not clenched into fists, but altogether lacking in fingers, and her legs end in stubs, entirely without feet. The physical impairments suffered in this hell mirror in many ways the deadening effects of alcohol in real life. The horrific implication of such an image was intended to aid the members of the monastic community in their efforts to remain faithful to the precepts, which stridently enforced a “zero-tolerance” policy toward alcohol consumption. Such imagery also provided a stiff rejoinder to the laity not to entice people with drink.

From this sad soul, the worshipper’s eye can bounce from one horrifying image to another within the tableau. All of the hells and admonitions that surround this husk of a human are not only depicted in sculptural form, but also lovingly detailed in narrative texts that accompany each work. Some of the most gripping are those to her left -the Boiling Cauldron Hell and the Hell of Feces and Filth.

The damned in Boiling Cauldron Hell are there for one reason only – they were the ones who cooked the meat [fig. 9]. Run by one of the horse-headed jailers in hell, considered a descendant of an earlier Indian god of the underworld, the worshipper is confronted by a suffering soul actually in the process of being tossed to his fate. Although many today view this as a somewhat comical image, given the preponderance of imagery akin to horse-head and his fellow jailer ox-head in contemporary comics, it is unlikely that medieval worshippers would feel inclined to laugh.

The Hell of Feces and Filth is presided over by a grotesque, fanged jailer who, with a mace in each hand, proceeds to beat back down the damned bobbing up out of the square vat of boiling feces [fig. 10]. The vat itself juts down and out so as to allow the worshiper the opportunity to see the struggling souls, two with faces up, as they gasp for air. One soul floats face down, an arm raised in supplication. The carved flames that encircle the sides of the vat increase the aura of noxious fumes suffocating the damned within. The inscription reads:

The scripture states that Kasyapa asked the Buddha, ‘Those who eat meat fall into which hell?’

The Buddha informed Kasyapa,

‘Those who eat meat fall into the Hell of Feces and Filth. Therein one finds feces and filth 10,000 feet deep, the meat eater is thrown into this hell, and repeatedly he goes through the cycle of immersion and exit. When he goes through the first cycle, myriads of spikes situated all around him stab and rupture this body, and serrate his limbs. This is the great torment (of this hell). For five million lifetimes, he knows no release.’

The accompanying inscription is not found near to the Hell of Feces and Filth, but rather carved on the front of a table depicting two men seated with plates in front of them, clearly meant to be a reference to a feast at which meat was consumed [fig. 11]. As if to confirm this fact, beside the two seated guests, a butcher can be seen straddling his block, upon which is placed an animal head already severed from the carcass.

The imagery accompanying the Admonition against Raising Animals is often reproduced, with many a commentator unaware of the grimness of the vignette [fig. 12]. Rhapsodizing on the lovely pastoral quality of the young woman who tends her hen and chicks, many scholars fail to realize that the fate that awaits her for just such an innocent act is not a pleasant one. Largely effaced, the gist of the inscription reads, “The Buddha told Kasyapa, “All sentient beings who raise chickens, enter into hell….”

One might expect to find these hells related to the punishments for raising and slaughtering animals to be placed directly below the king in charge of condemning a soul there, but in fact these hells are almost diametrically opposite the king. This disjuncture forces the worshipper to search the tableau for the appropriate image, no doubt creating a moment of confusion and panic similar to what one would expect a soul to experience in its journey through hell.

As one’s eye moves up the tableau, perhaps in the hope of finding help for one’s suffering, the next tier of hell does not provide much visual relief. The Hell of Cutting and Grinding is prominently placed at the very center of the next level [figs. 13 and 14]. The grinding aspect of this hell is vividly portrayed with a very prominent pestle, the crosspiece of which is being clutched by a particularly happy and hideous jailer, who applies his weight to the mechanism by a now-shattered left leg. He is also aided in his endeavors by a small, monkey-faced creature, while behind the pestle a figure cowers and covers her eyes with one hand rather than watch the torture occurring before her. The wickedness that produces such torture is also related to Buddhist prohibitions against taking life. Those who cut and chop up meat are doomed to suffer the same fate!

Fig. 13 The Hells of Cutting and Grinding at Baodingshan

Neither does the Freezing Hell offer much respite [fig. 15]. A reminder of karmic retribution is reflected in the inscribed verse, which refers quite pointedly to those who kill animals:

Breaking the fast and violating the precepts, you slaughter chickens and pigs. Illumined clearly in the mirror of actions, retribution will come without fail. If one commissions this scripture together with the painting of images, King Yama will issue a judgment that you be released and that your sins be eliminated.

This is the one of the few inscriptions at Baodingshan to cite a specific method to avoiding the tortures of hell. By commissioning scriptures and having images painted, a soul can be given absolution for his or her various sins associated with breaking the fast and killing animals. Within this level of hell, however, the vast majority of wicked behaviour that has brought one there is related to sins against the sangha, or Buddhist community. Not keeping feast days, not doing good deeds, or simply not following the Buddhist way are common explanations for the various types of tortures on display.

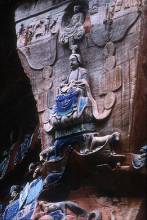

As one’s eye moves further up the tableau, it comes at last to an ordered world – that of the Ten Kings [fig. 16]. The Ten Kings and their attendants stretch across the cliff face in an orderly fashion, mirroring the symmetry of the meditating Buddhas above them. Although the second level is devoted mainly to the Ten Kings and their assistants, the image of Dizang Bodhisattva dominates [fig. 17].His position, seated on a lotus throne and central among the Ten Kings, yet linked to the heavens above and hells below, reminds the devotee of Dizang’s vow to save the damned. He is capable of releasing loved ones from their torments if their descendants perform the necessary rituals. These include having masses said for the dead, making images of Dizang, or but for one moment taking refuge in Dizang.[6]

Unlike Dizang, the Ten Kings are not depicted so much as sacred entities, but as men of justice. They are accompanied by attendant clerks, who carry the ledgers of merit and demerit by which the Ten Kings will pass judgment on the deceased [fig. 18]. The ritual practice related to the Ten Kings revolves around the premise that every soul passes in front of each of the kings at ten predetermined points over a three-year duration. These ten dates correspond to the’ seven-sevens’ – 7, 14, 21, 28, 35, 42, and 49 – designating the days after one is deceased, plus the 100th day, one year and three year anniversaries. On these days, offerings need to be made to each of the Ten Kings.

Introduced by the Officer of Immediate Retribution, the Ten Kings follow a standardized order of placement as given in the apocryphal Scripture on the Ten Kings, beginning with King Guang of Qin at the far right [fig. 19] The inscription accompanying this first attendant to one of the Ten Kings begins by decrying the most wicked of behaviours that will get a soul fast into hell, the evil of taking money from the church! The verse reads:

If one desires peace and happiness and to reside amongst men and gods, one must immediately stop taking money belonging to the Three Jewels. Once you fall into the hells within the dark regions of the underworld, there, amongst the clamor, you will receive punishment for untold years.

Fig. 19 King Guang of Qin at Baodingshan with his attendant

Lest one think that anyone is immune from the horrors of hell, it is important to consider the fate of the kings themselves. King Yama provides the best example. The fifth of the Ten Kings, King Yama, crosses both continental and ideological boundaries [fig. 20]. He is the original father of the afterlife in the Indian tradition. In China, King Yama came to be ruler of the underworld in both Buddhist and Daoist cosmologies. Originally king of the first hell and head of the underworld, King Yama was demoted due to his compassionate nature, and like all the beings in hell, must undergo tortures until his eventual rebirth.

Bringing together the entire hell tableau is the life-size figure of a monk carved directly beneath a pagoda almost central within the lowest level of hell and at eye-level with the worshipper [fig. 21]. His left hand is raised as if pointing to the images that surround him while his right hand clutches a bound sutra. Flanking him are the following carved inscriptions:

Heaven’s halls are vast and broad, yet hell is also vast; not believing in the Buddha’s word, then how the heart suffers! My Way is to seek pleasure in the midst of suffering, but all sentient beings (being confused) seek pain in the midst of pleasure.

While Dizang Bodhisattva may have enormous clout in the netherworld, they are intangibles when compared to a very real and present ‘this-worldly’ monk, such as is here portrayed in the very bowels of hell. As such, worshippers may have felt their salvation more readily at hand, more easily obtainable with just such a monk’s aid.

Integral to understanding the ritual relationship between the two tableaux is the small work, entitled Locking up the Six Vices [fig. 22]. The uppermost portion of the work is captioned in characters considerably larger than those seen elsewhere in the carving, and reads ‘Binding Tight the Monkey of the Mind and Locking Up the Vices of the Six Senses’. On each side of the figure are two symmetrical series of inscriptions. Immediately to the right of the figure’s head is the caption “Heaven’s halls and hell”, which is completed on the left side, “with one stroke are by the mind created”. In order to elaborate on this point, two rays emanate outward to the left and right from the central figure’s heart, like ribbons draped over the monkey image. Each ray leads out to a seed character of sorts, which will form the basis of a series of inscriptions flanking the central figure. These are larger characters set off in circles; on the right one reads “good (shan)” which flows upward to the character “good fortune (fu)”, which in turn leads to “happiness (le)”. To the left the seed character is “evil (e)”, which flows into “misfortune (huo)”, which eventually leads to “suffering (ku)”.

Directly below the central meditative figure cradling the monkey is a short inscription known as a “hell-breaking” verse:

If a person would wish to know all the Buddhas of the three periods, just discern that the Dharmadhatu [material world] is by nature generated entirely from the mind.

This short verse is in effect placed directly between good and evil, and their ultimate rewards. Moreover, this verse can be seen to link the hell tableau to the worshipper’s left with the Pure Land work on his or her right, a sensation which is reinforced by the two emanations of good and evil, which flank their respective recompense. Good leads the worshipper’s eye to the glories of the Pure Land; evil connects the individual with the sufferings of the damned. Used within a ritual context, the hell-breaking verse represents a way to pass from one existence to the next.

At Baodingshan, the worshipper was first shown the beauties and wonders of the Pure Land heavens only to then be presented with the horrors of hell. Such a powerful contrast would most likely have had an edifying effect. A worshipper might easily have imagined not only themselves, but also their loved ones as being among those suffering the torments of hell. This incurred a certain amount of doubt among the faithful, thereby prompting them to insure the more pleasant fate by performing the necessary rituals. It is an interesting point to ponder how the theme of pain and torture kept the Buddhist congregation busy and prosperous!

Lest one think that Buddhist hell fell out of fashion after the medieval era, this was not the case. Images of hell continue to be produced to this day, mainly in portable format, and are still part of funerary rites. Modern sculptural renditions are rare, and those that exist tend to elicit more laughter than fear [fig. 23].

Select Bibliography

Dazu shi ke ming wen lu. (The Collected Inscriptions from the Dazu Stone Carvings). Chongqing: Chongqing chu ban she, 1999.

Cohen, Myron. “Soul and Salvation: Conflicting Themes in Chinese Popular Religion” in Death Ritual in Late Imperial and Modern China, 180-202. Watson, James L. and Evelyn S. Rawski, eds. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1988.

Deng Zhijin. Dazu Baodingshan Dafowan liu hao tu kan diao cha” (An examination of the liuhaotu niche at the Great Buddha Grotto, Baodingshan, Dazu). Sichuan wen wu 1(1996): 23-32.

Goodrich, Anne Swann. Chinese Hells: The Peking Temple of Eighteen Hells and Chinese Conceptions of Hell. St. Augustine: Monumenta Serica, 1981

Guo Licheng. Shitien yanwang: Weiboru juanzeng – Ten Kings of Hades : The Vidor Collection. Taibei: Guoli lishi bowuguan, 1984.

Hu Wenhe. “A Comparative Study of the Paradise Bianxiang in the Sichuan and Dunhuang Grottoes”China Art and Archaeology vol. 1 no. 2 (1996): 7-16.

. “Lun di yu bian xiang tu” (A Discussion of Hell

Transformation Tableau Imagery) Sichuan wen wu 2 (1988): 20-26.

Matsunaga, Daigan and Alicia. The Buddhist Concept of Hell. New York:

Philosophical Library, 1972.

McKnight, Brian E. Law and Order in Sung China. Cambridge, England and New York: Cambridge University Press, 1992.

________________________________________________________________

[1]It is in large part due to the lateness of its construction that the Baodingshan complex has received limited attention from modern-day art historians. Buddhist sculpture produced after the Tang dynasty has only recently been considered as a subject of study because most earlier art historical scholarship perceived the Tang as the high point of the Chinese sculptural tradition, with all later works viewed as derivative or inferior. My work, Cliff Notes: Text and Image at Baodingshan, PhD diss. 2001, is the only one that treats the interplay between text and image at the site.

[2]The images come from the aprocryphal Chinese Scripture on the Visualization of the Buddha of Infinite Life (Guan wu liang shou fo jing). All text translations are by the author, and are based upon transcriptions found in Dazu shike ming wen lu (The Collected Inscriptions from the Dazu Stone Carvings) Chongqing: Chongqing chu ban she, 1999, and photos taken of the inscriptions on site by the author.

[3]Amitayus is a variation on Amitabha, meaning “of immeasurable life span” versus Amitabha’s “of immeasurable radiance”.

[4]Although size, weight, and construction were explicit in the penal code, officials often were accused of using injurious cangues, such as the four-layer cangue in which wrought iron and uncured rawhide were attached to raw wood, the resulting effect being one of shrinking and squeezing as the rawhide dried.

[5]All photographs are by this author unless otherwise noted.

[6]These can be found in chapter seven of the eighth century Sutra on the Origins of Dizang Bodhisattva.