Shunga and Ukiyo-e: Spring Pictures and Pictures of the Floating World

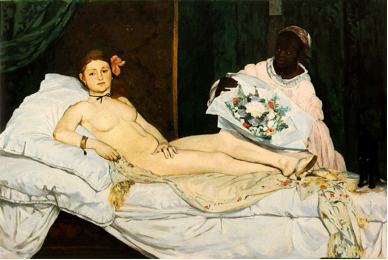

Shunga, or ‘spring pictures’ is a branch of Japanese art dedicated to the erotic. For the Japanese “sex represented neither a romantic ideal of love, nor a phallic rite to the gods; it was simply the joyful union of the sexes” (Rawson 283). For the artist, shunga was a normal function, similar to the nude paintings done by Eduard Manet (see Figure 1). Their type of art does not say anything about the artist’s morals, or apparent lack thereof. In fact, there was little or no moral stigma attached to shunga until the late 19th century.

The purpose of the shunga was that of sexual education, with an emphasis on procreation and family continuity. The audience was often seeking advice for improving their sex life (either practically or emotionally) since there were few medical texts available that dealt with sex. The ones that were readily accessible were Japanese translations of old Chinese medical texts, and they often required at least some familiarity with medicine. In addition, “as late as the 1930s…it was still the practice among certain of the more traditional Japanese department stores to include a shunga volume in the corner of a chest-of-drawers purchased for a prospective bride” (Rawson 285). In comparison to western sex books, which only came about in recent times, Japanese shunga, which arose already in the 17th century, were a union of science and art, while the western sex books were thought of as cold and scientific. There was also a serious belief given to conjugal compatibility in accordance with natural or divination-like forces. Books of sexual astrology arose that depicted both the good and bad consequences of men and women that were born under compatible or opposing zodiac signs. Sex was considered to have an undeniably beneficial effect on health and longevity, which most likely stemmed from China and their need for an intellectual approval of sex. This approval then smoothed the way for erotic publications aimed towards the samurai class, which might have otherwise restricted them.

Shunga often bore close relationships to literature of the time, since certain literary situations often became ‘in vogue’. For example, the banning of foreign travel in the 1630s brought on the tale of a hero’s shipwreck to a distant island of ‘lusty females’. It can be said that shunga is a clear reflection of the tastes and manners of the times in which they were created.

Nearly all Japanese shunga were originally designed as part of a unified series. In general, hanging scrolls are rare because of their more public nature, and the shunga’s more private subject matter. The more intimate picture (hand) scrolls and albums predominate, though in non-erotic art, the opposite is the case. Most shunga are now removed from their original settings, and scenes are split up from their original scrolls. This is probably due to modern day art dealers censoring images for purchasers, who want more ‘tame’ images. In older Japan, the government was generally complacent towards sexual expression. In contrast, modern Japan arose in the midst of the Victorian age, and adopted most of the supposed sexual repressions of the late 19th century Western society, which it used as its model. As a result, both the European nude and the Japanese shunga were banned.

Pre-historic Japanese erotica consisted of the phallic symbols and fertility images of the early indigenous religions. With the importation of Buddhism in the 6th century the artistic tradition became filled with images and iconography, but not of erotic nature. In fact, many Buddhist deities were asexual, and the female forms that did emerge were idealized feminine depictions. For example, one of the more sexually depicted deities was Kangiten (from the esoteric Shingon sect) who is often depicted as a male and female pair in a standing embrace featuring human bodies and elephant heads.

Some of the earliest forms of Japanese shunga are attributed to Buddhist monks. Oftentimes, so-called ‘graffiti’ is found at the bases of statues in Buddhist temples (see Figure 2). This particular sketch was found at the base of an early 7th century sculpture at Horyuji temple, and depicts a woman at the top of the sketch and a phallus below her. Even though sex life for the general public was ‘free’, the stifling life of a Buddhist monastery provided the need for sexual outlets, often in the form of rough sketches.

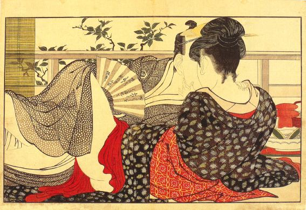

Mere nakedness held little erotic interest to the Japanese viewer, which may explain why Japanese erotica is so extreme in its sexual depictions and why many of the erotica depicts clothed or half clothed figures (see Figure 3). At this early time in shunga development, art for its own visual sake was probably nonexistent. Most painting during this period was intimately connected with Buddhist tenets which explained divine origins of shrines or temples, or illustrated famous tales, such as the Tale of Genji.

Shunga found a permanent art form with the development of the hand scroll. The shunga depictions of the Edo period (1600-1868) left the story format and began to be presented as unrelated erotic scenes. This became known as ukiyo-e, which often took subject matter from the people and customs of its own time. During the Edo period, erotic art became an object of appreciation for the urban population in general-not just for the wealthier samurai class and the aristocracy. This could be attributed to the expansion of woodblock printing, which was no longer limited to the monastic presses. The first dated ukiyo-e shunga book was the Yoshiwara Pillow-pictures, dated to around 1660. This was an illustrated guide to the courtesan quarters of Japan. Similar books exist, but do not utilize shunga, they only feature critiques of famous courtesans. The Yoshiwara Pillow-pictures is made entirely of illustrations, each page featuring a famed courtesan of the time, identified by her family crest.

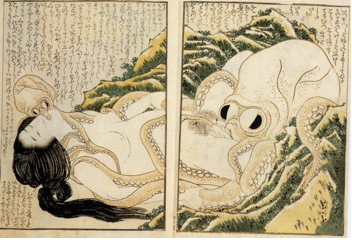

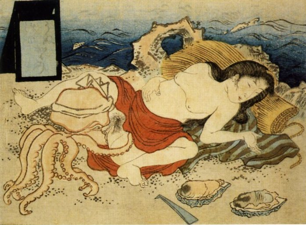

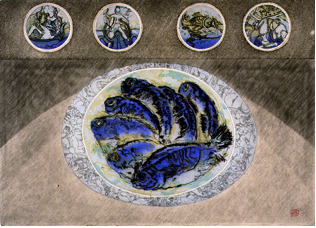

During the Edo period, Ukiyo-e print artists were supported by the thriving middle class, which became a vital force of the Edo period culture. The recreational aspects of sex, such as the courtesan quarters were allowed to flourish during this time, along with erotic literature and art, which were also allowed to become widespread and fashionable. It was during this period that ukiyo-e and shunga imagery became widespread. Among the most interesting of these images are those involving sea creatures and women. Most likely associated with the story of Tamatori, the abalone diver who sacrifices her life to save the emperor, they often depict an octopus or other sea creature performing oral sex on a woman. The legend goes that Tamatori cut open her breast where she had hidden the jewel she stole from the Sea-Dragon King in his underwater Palace (see Figures 4 and 5). At this point during the Edo period, the ukiyo-e began to develop different symbolic layers, the first being the erotic image itself, then the placement of the print in the series, the third being the text that often accompanies the print, and the fourth which lies in the symbolism hidden deep within the piece, such as in kimono motifs. Taking the Hokusai print as an example, the first layer is the erotic image of the encounter between the girl and the octopus. The second layer would be how that specific print interacts with the other prints in the same series; the third would be the interpretation of the accompanying text, which in this instance is a dialogue between the creature and the diver expressing mutual sexual enjoyment. The fourth layer deals with symbolism in the piece. In this instance, symbolism could arise in what kind of sea creature is used, and in the popular story of the abalone diver Tamatori. Noboru Sawai’s Fisherman’s Dream (see Figure 6), could be seen as being influenced by this legend.

The genre of shunga began to decline after its peak in the last quarter of the 18th century. By the middle of the 19th century it was rare to see a print anywhere near the level of the earlier works. “The fault was largely that of the age: the public, stagnant after too-long centuries of seclusion from the outer world, had lost its taste for figure-prints of grace and lovely harmony” (Rawson 369). The final death was with the arrival of Commodore Perry in 1858, at which point what was left of old Japan’s shunga tradition was replaced by a different civilization’s traditions.

Figure 1

Figure 1

Edouard Manet, Olympia, 1863, oil on canvas

Figure 2

Figure 2

Sketch in sumi on wooden base of early 7th-century sculpture, Horyuji temple, Nara

Figure 3

Figure 3

Kitagawa Utamaro, Poem of the Pillow (Utamakura), 1788, woodblock print

Figure 4

Figure 4

Katsushika Hokusai, Kinoe no Komatsu (Young Pine Saplings), 1824, woodblock printed book, three volumes

Figure 5

Figure 5

Yanagawa Shigenobu, Suetsumuhana (A Dyer’s Saffron), c. 1830, woodblock, series of 12 prints

Figure 6

Figure 6

Noboru Sawai, Fisherman’s Dream, 1991, woodblock relief print

References

Rawson, Philip. Erotic Art of the East: The Sexual Theme in Oriental Painting and Sculpture. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1968.

Screech, Timon. Sex and the Floating World: Erotic Images in Japan, 1700-1820. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1999.

Uhlenbeck, Chris, and Margarita Winkel. Japanese Erotic Fantasies: Sexual Imagery of the Edo Period. Amsterdam: Hotei Publishing, 2005.