Ben Landsteiner

A Detailed Look at the First 50 Years of Growth in Yoshida Toshi

By the time Hiroshi and Fujio Yoshida had Yoshida Toshi, their eldest son, the Yoshida name was already well established within the art world, thanks originally to Toshi’s grandfather, Kosaburo Yoshida. It is necessary to analyze Toshi’s lineage in order to see how it affected his own growth as an artist. Kosaburo lived during the Meiji Restoration, and so he was part of the first wave of Japanese artists to be influenced by foreign art. Kosaburo’s work itself was a blend of traditional Japanese art mixed with a strong Italian influence. Kosaburo, fearing that he would never produce a male heir, adopted Hiroshi so as to secure his tradition in the next generation. Kosaburo did eventually produce a male heir, but thought so well of Hiroshi that he was chosen to remain as first son anyway.

Hiroshi himself started out working with oils, much like his adopted father. All of his creations were realist in style, and he vehemently avoided some of the more newer, abstract trends in the art world. In 1920, by the age of 44, Hiroshi was well known for doing oil and watercolor paintings of landscapes. Around this time, Hiroshi began to experiment with woodblock prints. During a trip to the United States, Hiroshi brought with him many of his already-famous paintings and a few of his woodblock prints. What he found was that the West was far more interested in woodblock prints, more specifically ukiyo-e, making Hiroshi “think that the Japanese had better get busy in the field that was once their own.” His switch to woodblock prints was compounded by the fact that other offerings on the market were of generally low quality, and he believed he could successfully compete by integrating Western style into traditional, Japanese style prints. In other words, he used some artistic techniques of the West, but retained the same subjects as before. The change from oils and watercolors to prints paid off, as the family became wealthier, and Hiroshi became one of the leaders in shinhanga, or “new prints.”

On July 25th, 1911, Toshi Yoshida was born. Within his first year of life, Toshi contracted polio meningitis, leaving him crippled for life. One of his legs was rendered almost entirely useless. Therefore, from a young age, Toshi was unable to do what normal children did—play outside. Instead, starting at about the age of three, he and his parents, and occasionally his playmates, would have drawing contests. By 1915, he was already receiving lessons from his father.

In 1923, Toshi’s parents went on a multiyear journey to the United States, leaving Toshi at home with an Uncle of his in Tokyo. This stay was crucial to his development as an artist, as it allowed him the opportunity of sketching animals in a local pet store. Furthermore, his Grandmother named Rui encouraged his interest in animal sketches, in large part because Rui considered this to be a way in which Toshi could differentiate himself from his father, since his father specialized in landscape prints.

As mentioned previously, upon returning from the United States, Hiroshi Yoshida became interested in making prints. Due in large part to the family fortune acquired through Hiroshi’s popularity as an oil and watercolor artist, the family was able to make its foray into woodblock printmaking. Toshi’s first work, Crabs, was produced when he was only 14!

When Toshi was 19 years old, he traveled with his father to India, a form of rite of passage. Toshi sketched everything that he could, and during this time his skill greatly increased. Sketchbooks show that Toshi’s ability to handle perspective increased as the trip progressed, and that upon their return to Japan, Toshi was capable of portraying scenes as well as his father. Unfortunately, upon their actual return, Toshi became weak; he had, after all, just traveled the rest of Asia with a limp leg. A big part of the problem lay in Hiroshi and Toshi’s relationship; Hiroshi was a demanding father, and Toshi was coming of age, a combination ripe for trouble. Grandmother Rui intervened, and helped nurse Toshi back to health. Hiroshi disallowed Toshi from reading newspapers or listening to the radio, so he had little concept of the outside, Western world. Grandmother Rui changed this by letting Toshi explore Western music and literature; in other words, Toshi was finally exposed to Western culture.

When Toshi was 19 years old, he traveled with his father to India, a form of rite of passage. Toshi sketched everything that he could, and during this time his skill greatly increased. Sketchbooks show that Toshi’s ability to handle perspective increased as the trip progressed, and that upon their return to Japan, Toshi was capable of portraying scenes as well as his father. Unfortunately, upon their actual return, Toshi became weak; he had, after all, just traveled the rest of Asia with a limp leg. A big part of the problem lay in Hiroshi and Toshi’s relationship; Hiroshi was a demanding father, and Toshi was coming of age, a combination ripe for trouble. Grandmother Rui intervened, and helped nurse Toshi back to health. Hiroshi disallowed Toshi from reading newspapers or listening to the radio, so he had little concept of the outside, Western world. Grandmother Rui changed this by letting Toshi explore Western music and literature; in other words, Toshi was finally exposed to Western culture.

After returning to health, Toshi entered an art school that was dominated by European methods, and it is here that Toshi produced his first oil paintings. While learning, Toshi reverted mainly to his father’s subject material: landscapes. This was probably due to the school Toshi attended (his father had been one of the founders), and because he was trying to learn the nuances of oil paintings. After graduating and by the end of the 1930s, differences in Toshi’s style as compared to Hiroshi’s became apparent. According to Skibbe, “Hiroshi had been drawn to nature clothed in mist or clouds or the half-light of dawn or dusk, and from such moments he wanted to distill a feeling of transient beauty or partly revealed mystery. Toshi in contrast preferred full light, clear definition, expressing a sense of calm or stability underlying objective reality.”

For a few years after his post-art school years, Toshi stopped making prints. His school specialized in oil works, so that is what he created. The capstone of his paintings can be seen in Ishikiriba (1939), an oil painting made to win the heart of his future wife, Kiso. It is said to show Toshi at his best in oils.

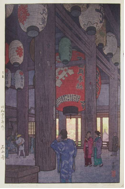

In 1938, right before Toshi and Kiso married, Toshi began to experiment with woodblock prints once more. From such works as Shinjiku (1938) and From the Ryogoku Bridge (1939), one can see that whereas Hiroshi preferred to obscure objects in a misty haze, Toshi preferred to make things more clear-cut.

Toshi’s move back to woodblock prints came at an interesting time in world history. The government increasingly began to censor artists, and with Japan attacking the United States in 1941, the woodblock print market that the Yoshida family catered to went dry; selling to the enemy was unthinkable and impossible. In addition, Toshi’s style was greatly influenced by Japan’s national policy. Every Japanese citizen was expected to at least give the appearance of being nationalistic. Hiroshi complied completely, making several trips to China (who Japan was also fighting), where he created prints of “peaceful Chinese scenes.” He also made prints of sites in Japan that portrayed a sense of national spirit. Toshi, on the other hand, both attempted to differentiate himself from his father and reject the nationalistic images that were becoming popular. He avoided “dramatic atmospheres and painterly effects” and instead focused on the “little people” who made the war possible. Iron Factory (1943) portrays “Heroic Japan in the form of common laborers,” and Toshi shows signs of an “interest in light, shadow, and color” here.

Postwar Japan in 1945 marks a momentous change for the Yoshida family. Where does one begin? First, and ultimately most importantly, Hodaka, Toshi’s younger brother, began experimenting with abstract oil prints, something Hiroshi vehemently despised to the point where Hodaka kept it a secret. Hodaka went down this path partly because he yearned to do something different from both his father, Hiroshi, and the rest of his family. Toshi discovered Hodaka’s secret, and would occasionally watch and experiment with him. From a cultural perspective, Hiroshi’s rejection of abstract art makes sense; it has been theorized that abstract art was not popular within Japan at this time because it wasn’t “conducive to the Japanese character” and there still remained “a love of surviving traditional scenes and a desire to portray them before they disappeared.” In other words, there was a strong desire to preserve the old. A second important change is that Toshi began to defy his father even more. He made a print, Ishiyama Temple (1945-6), which was twice the size of his previous prints; something his father believed was impossible and greatly discouraged. In addition, as a result of Hodaka, Toshi increasingly experimented with more abstract concepts.

Evidence of Toshi’s interest in abstract paintings surfaces in the oil painting Sunlight Patterns in Shallow Water (1947). The beauty of this piece is that it satisfied his father—who abhorred abstract art—as well as his inner desire to experiment. He was able to play with the light on the water and to investigate pattern and color while still drawing upon a natural subject.

Toshi discovered another “loophole” when he decided to do Microbe Landscape (1950). While still an image of something natural, Toshi was also able to choose his own color palette due to the drab look of the specimen under a microscope. So while it may at first appear to be entirely abstract, it is in reality realistic and yet foreign to the viewer.

In 1950, Hiroshi passed away, and Toshi became the head of the family. While certainly a sad time for the family, it finally allowed Toshi and others in the family to fully embrace the abstract movement. Hodaka, of course, had already completely embraced an abstract style well before the death of Hiroshi, but within a year of Hiroshi’s death, both Toshi and Hiroshi’s wife, Fujio, had created their own abstract or semi-abstract pieces. During an interview a few years after his father’s death, Toshi stated that “from these paintings [Microbe Landscape et al] it was an easy—I suppose inevitable—step to abstraction, but it was a step my father could never approve. Still, I could not ignore the movement of the times and I began to break away from my former realistic approach two or three years after the war.” The ‘movement of the times’ is referring to the Japanese general public’s eventual acceptance of abstract art in post-war.

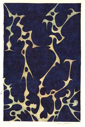

In 1952, after successfully experimenting with abstract themes in oil paintings, and with the restraints and pressures his father put on him removed, Toshi made his first abstract woodblock prints. Initially, Hodaka’s influence could easily be seen amongst Toshi’s prints, although gradually the techniques and skills Toshi acquired while working with oil paintings began to appear on his woodblock prints as well. Upon returning from the United States in July 1954 (Toshi had spent 10 months there establishing connections and advertising the family’s wares), Toshi set out to improve upon some of his earlier abstract woodblock prints. Below is a comparison of No. 10 (1952) and Dragon B (1955).

|

|

Clearly the image on the left is No. 10, since it is much simpler than Dragon B, which came three years later. Whereas Toshi is experimenting with the former, he has molded it into an abstract image in the latter. Aside from colors, Dragon B seemingly looks like No. 10 at first glance. A more rigorous look reveals an image of a dragon.

While making his foray into abstract woodblock prints, Toshi also rekindled his interest in making traditional landscape prints, perhaps due partially to the death of his father, since it was his specialty. Toshi’s were unique in that, much like his prints of the common man during wartime Japan, his landscapes were of “the common realities beautiful to the Japanese heart.” A perfect example of this style is Morinji in Spring (1951) with, among other things, two common farmers fishing in the meandering river.

Only half of Toshi’s artistic career has been touched upon. After his foray into abstract and landscape prints, Toshi became interested in African themes (after, of course, visiting Africa). This reignited Toshi’s interest in animal prints, and eventually Toshi tackled a new creative project, a children’s collection called Animal Picture Book Series (Dobutsu ehon shirizu), of which he published 17 of 20 volumes. He died in 1995, still trying to finish the last three volumes. In the final 20 years of his life, Toshi taught one of his sons and many other apprentices his craft, so as to insure the Yoshida tradition for a fifth, but not final generation.

Statler, Oliver. Modern Japanese Prints: an Art Reborn. Rutland, VT: Charles E. Tuttle Co., 1956.

Skibbe, Eugene M. Yoshida Toshi : Nature, Art, and Peace. Edina, MN: Seascape, 1996. 34.

Statler, Oliver. Modern Japanese Prints: an Art Reborn. Rutland, VT: Charles E. Tuttle Co., 1956. 171.

“Shin Hanga.” Artelino. 3 May 2006 <http://www.artelino.com/articles/shin_hanga.asp>.

“Yoshida Bio.” Hendrick’s Art Collection. 3 May 2006 <http://www.hendricksartcollection.com/yoshida.html>.

Skibbe, Eugene M. Yoshida Toshi : Nature, Art, and Peace. Edina, MN: Seascape, 1996. 37.

Skibbe, Eugene M. Yoshida Toshi : Nature, Art, and Peace. Edina, MN: Seascape, 1996. 39.

Skibbe, Eugene M. Yoshida Toshi : Nature, Art, and Peace. Edina, MN: Seascape, 1996. 39.

Skibbe, Eugene M. Yoshida Toshi : Nature, Art, and Peace. Edina, MN: Seascape, 1996. 40.

Skibbe, Eugene M. Yoshida Toshi : Nature, Art, and Peace. Edina, MN: Seascape, 1996. 41.

Skibbe, Eugene M. Yoshida Toshi : Nature, Art, and Peace. Edina, MN: Seascape, 1996. 44.

Allen, Laura W. et al. A Japanese Legacy: Four Generations of Yoshida Family Artists. Minneapolis: Minneapolis Institute of Arts, 2002. 74.

Skibbe, Eugene M. Yoshida Toshi : Nature, Art, and Peace. Edina, MN: Seascape, 1996. 46.

Skibbe, Eugene M. Yoshida Hodaka : the Magic of Art. Edina, MN: Seascape, 1997. 14.

Terada, Toru. Japanese Art in World Perspective. Trans. Thomas Guerin. New York: Weatherhill, 1976.

Skibbe, Eugene M. Yoshida Toshi : Nature, Art, and Peace. Edina, MN: Seascape, 1996. 48.

Allen, Laura W. et al. A Japanese Legacy: Four Generations of Yoshida Family Artists. Minneapolis: Minneapolis Institute of Arts, 2002. 75.

Skibbe, Eugene M. Yoshida Toshi : Nature, Art, and Peace. Edina, MN: Seascape, 1996. 53.

Skibbe, Eugene M. Yoshida Hodaka : the Magic of Art. Edina, MN: Seascape, 1997. 15.

Statler, Oliver. Modern Japanese Prints: an Art Reborn. Rutland, VT: Charles E. Tuttle Co., 1956. 169.

Terada, Toru. Japanese Art in World Perspective. Trans. Thomas Guerin. New York: Weatherhill, 1976.

Skibbe, Eugene M. Yoshida Toshi : Nature, Art, and Peace. Edina, MN: Seascape, 1996. 57.

Allen, Laura W. et al. A Japanese Legacy: Four Generations of Yoshida Family Artists. Minneapolis: Minneapolis Institute of Arts, 2002. 79.