Sometimes academics who want to learn more about a project I’m working on will pose a question like “is your project curricular or research?” Sigh. Really?!

The disagreement on the intersection of theory and practice in academia is not a new one, but I do believe it is one that is changing. And, my research is arguably a bit unique in that both my coursework in my M.A. and my Ph.D. focus on the how a learner experiences and is motivated by the curriculum and environment in which they are learning. So, for me it’s not possible to separate curriculum development and research. My teaching and research interests are interdisciplinary as well, drawing on the fields of Applied Linguistics, Foreign Language Learning, Educational Technology, Online Learning, and Distance Education. Additionally, my work typically has Norwegian as the language of instruction though I’m not actually researching the language itself. Essentially, much of what I do is within the field of the scholarship of teaching and learning; I examine my teaching and my students’ learning to advance the practice of teaching and learning.

I’ve used technology extensively in my teaching through Distance Education courses and Face-to-Face courses using a Course Management System (CMS) called MOODLE. My dissertation examined student practices of Distance Education Foreign Language Learners. Through these teaching and researching experiences, I became increasingly interested in how students experience an online learning environment differently from a face-to-face environment. By the time I entered the field, research had moved beyond Media Comparison Studies (see the No Significant Difference site for more on this); the majority of DE educators and researchers were calling for in-depth exploratory studies of Distance Education (Kearsley, 1999).

Essentially, the core of the Sett i gang web portal was built from an understanding of how theory and practice meet in my interdisciplinary fields. I have been asked to share some concrete examples of this. I have also started to receive some inquiries from colleagues who teach from the Sett i gang curriculum, wanting to know more about where the next edition is headed. So, here goes…

10 research findings utilized in the development of the Sett i gang Web Portal:

1. Immediate feedback

Ex. 1: Immediate feedback

I believe that immediate feedback is one of the most valuable tools of the portal. Several studies have documented students’ need for prompt and meaningful feedback in online learning environments (Northrup, 2002; Brown, 1996). Many CMSs are capable of grading of activities which have set answers. Results are recorded and students (and in some cases) their instructors are able to monitor their progress (see Example 1 to the left).

In my dissertation study, I found that the completion of this type of activity was a predictor of both course completion and linguistic outcomes (Lie, 2008). In my teaching, I have also found that students are far more likely to re-do a homework answer that is incorrect if it is online rather than the traditional model of me handing back workbooks with incorrect answers noted in red ink. It makes sense – when a learner is doing their homework, they are focused on it right then. Delayed, traditional feedback (me handing it back to them a week later) interrupts that process.

When students are in a learning environment which fosters this type of immediate feedback, and can master a number of tasks which scaffold from one to the next, some will be able to experience what psychologist Csíkszentmihályi (1990) refers to as “flow”. Flow theory posits that learners are able to absorb and concentrate more when in this state and that it optimizes their learning experience. Csíkszentmihályi identified a number of elements that are needed in order to achieve flow, one of which is immediate feedback.

The majority of the activities in the portal give students feedback so they can monitor their progress and make multiple attempts in order to master each of the linguistic forms and vocabulary before moving on to the next.

There are additional benefits to the system created in the portal which provides feedback. Although it takes considerable time, and in some cases, money, to create and program learning activities in a CMS, not having to grade piles of fill-in-the-blank answers, the same ones every semester, frees up faculty time (even if only after the activities are programmed in). With that time I’m able to focus more on giving feedback on other assignments, specifically the individualized written or audio recorded assignments which don’t have set answers. This is a much more valuable use of my time and more beneficial for my students as well.

2. Proximal goals & Mastery Experiences

For many students, completing a language course is a daunting, overwhelming experience. Students riding the struggle bus need encouragement to keep motivated. And of course students who aren’t struggling need encouragement and motivation too!

Bandura’s (1986) investigation on how goals correlate with achievement outcomes posits that students who divide up objectives and master objectives one at a time (a proximal goal) rather than one large final goal (a distal goal) show increased commitment and motivation.

If we look at the bigger picture of goal setting and completing tasks, a learner’s belief in their ability to succeed also affects their learning. Bandura (1986) defines this “do I have what it takes to be able to complete this?” question as self-efficacy. A resilient sense of self-efficacy requires overcoming obstacles through perseverant effort which he refers to as an enactive mastery experience. In other words, students will feel more confident in the future if they have already completed something successfully.

Ex. 2: Flashcard sets

The application of Bandura’s findings work in tandem in the portal. By dividing the course content into smaller, more manageable chunks, we can help our learners create distal goals. One example of how we’ve used distal goals is with the creation of flashcard sets within each chapter as seen in Example 2. Here students can practice vocabulary in both written and audio form in small sets (from 5-15 words); when they are ready, they can combine these sets to create one large set with all of the words from the chapter or even the entire semester. This allows students to work with a comfortable amount of information and to focus on one piece at a time.

Ex. 3: Utgang

Another example of how we’ve used Bandura’s findings is with the creation of utgang. Utgang translates to exit; we use it as a way to check mastery of each section (after three chapters). Completing the utgang is an exit to each section thus completion means they are ready for the next section. The utgang assesses the language students should have mastered in the section including both grammatical forms and vocabulary, but this time in a much larger chunk than previously assessed. One of the central goals of the utgang is to instill confidence in the learner, to get them from “I don’t really know how I’m doing, I have done everything in smaller chunks but do I know how to put it all together?” to “yeah, I got this and I’m ready to move on!”

In practice, at St. Olaf for example, students complete the utgang before a more formal, in-class written test. This then gives students the opportunity to see how well they have mastered the materials before taking the test. Students report that they feel more prepared for the test when they complete the utgang first, which is exactly what Bandura’s enactive mastery experience is all about; it’s coming to the test thinking “I know I can do this because I’ve successfully completed the utgang“.

3. Advance Organizers

Each unit (3 chapter sequence) begins with a short video introduction. This video introduction is used as an Advance Organizer (AO). Ausubel (1968) first conceptualized AOs as a part of his theory of meaningful learning and retention. Chen (2014) explains AOs as:

- organizational cues

- tools that help connect the known to the unknown

- frameworks for helping students understand what it is they’ll be learning

AOs can come in varying formats such as text, graphics, or hypermedia. Ausubel found the use of AOs assisted learners in activating prior knowledge for the new instructional context and made the instructional process meaningful.

There have been many follow-up studies on the use and possible benefits of AOs (see Chen & Hiumi for a discussion). In Chen & Hiumi’s (2009) study, which controlled for both learning outcome & prior knowledge, they found that students of low ability performed better with an AO in both the short-term and long-term tests than those without an AO. They state that “[t]he use of AOs helped them cultivate a meaningful learning process by well organizing the relevant knowledge structure, and develop an emotional commitment by integrating new knowledge with existing knowledge” (np).

Since we have an utgang (exit) to each of the sections, we thought it appropriate for these video introductions to be conceptualized as an inngang (entrance). Thus, the purpose of the inngang is for students to think about what they will be learning, to provide a structured framework in which they will be able to take in new information; it marks their entry into a new topic (note also the visual of a door on the inngang). Additionally, it connects to what they already know, which can spark interest and motivation.

Ex. 5: Innblikk

4. Culture

Culture is so intertwined in our understanding of language that many refer to it as the fifth skill (the first four skills being reading, writing, listening and speaking). Culture includes recognizing, accepting and valuing cultural differences. The National Standards for Foreign Language Learning (1999) state that students “cannot truly master…language until they have also mastered the cultural context in which the language occurs.”

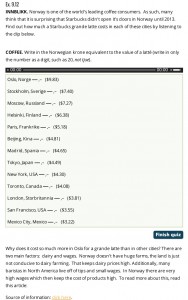

A very early and deliberate decision was to find new ways in which to bring out the culture each chapter is built upon. One of the ways we did this was to include three innblikk (insights) to Norwegian culture in each chapter that either expand upon the innblikk in the textbooks or touch on new cultural points (totaling 90). This isn’t the only place culture is in the portal, but in these activities, it is the focus. Some of the innblikk are visual, some have an activity, some link to other sites, some are in English while others are in Norwegian; they are all connected to the larger cultural topic of the chapter. In line with the National Standards, we have included varied forms of culture: cultural products, practices and perceptions. In Example 5, you see an example of an innblikk, this one furthering the topic of the coffee culture in Norway and why a Starbuck’s latte is so expensive in Norway, which links together both cultural products and perceptions.

5. Authentic Texts

One way in which culture is introduced in the portal is with embedded or texts linked to other online resources. Note, that I’m not limiting the word text to only that which is written. In fact Example 6 is an activity using a Norwegian commercial. I like using commercials in my teaching because they are short and often very fun(ny), because Norwegians have really good commercials and finally because they are authentic.

Authentic texts can be defined as being created for native speakers, not for language students (Harmer, 1991). Lee (1995) goes further to state that authenticity is produced for real communicative purposes. While I do believe adapted texts (texts intended for language learners) are also important, a number of advantages of using authentic materials have been found including an exposure to “real” language and culture, a positive effect on learner motivation, and supports a more creative approach to teaching (Berardo, 2006).

Ex. 7: Clip from show

Example 7 is a clip from the Norwegian reality show “Alt for Norge” where Americans compete to see who is the most Norwegian, here by eating smalahove, a sheep’s head. This is a clip they watch right after having done an exercise on traditional Norwegian delicacies. But in this example, because the host of the show is speaking to a group of Americans, it is in English with Norwegian subtitles. So, students can read the subtitles. Both examples were created for Norwegians by Norwegians, and expose learners to real language and culture.

6. Authentic Tasks

In addition to using authentic texts, using language in an authentic way is also very beneficial for learners. An authentic task is something that provides students with a real-world relevance. Reeves, Herrington, Oliver & Woo (2004) argue that, “value of authentic activity is not constrained to learning in real-life locations and practice, but that the benefits of authentic activity can be realized though [sic] careful design of Web-based learning environments” (5). They go on to state that “a well-designed activity can be so much more than an opportunity for students to practice and apply their learning… the activity students perform as they complete a course of study is the single most important element in the design of the learning environment” (6).

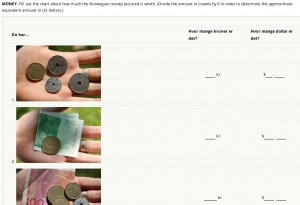

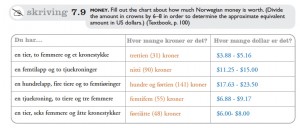

Because the Sett i gang curriculum has been around awhile, there are certain exercises that I’ve thought long and hard about how to improve. Quite possibly one exercise I was most excited to re-conceptualize was on kroner, Norwegian crowns (currency). A similar exercise existed in the workbook students previously used, but the black and white printing limited the number and the type of visuals we were able to use.

Ex. 8: Old Workbook Exercise

As you see in example 8, the old workbook the exercise focused on counting numbers where students had to figure out the sum of the money (a 10 crown coin, two 5 crown coin, and one 1 crown coin) and it’s equivalency to USD (here you see the answers written in red and blue). The new version of this exercise is shown in example 9. Here we’ve been able to make the task more authentic by portraying a student holding a handful of kroner. This replicates the “What do all of these coins and bills add up to? Do I have enough money to purchase X? And what is that equal to in dollars?” which are all real questions we ask ourselves when at the grocery store in another country.

Allow me a short digression… one great benefit I have in authoring a portal instead of a new edition of the workbook is that I can change things more easily. In this exercise for example, if the exchange rate changes, I can re-program new answers. While writing this blog post, I also realized two ways in which this exercise could still be improved. First, it is very US-centered. Because we will have a number of students in Canada using the portal in the future, I could, for example change the directions slightly to read convert to either USD or CAD and program in CAD equivalencies. Second, since I had created this exercise with a grocery store and a broke student in mind, it could include one additional step. A column could be added where there is a picture of an item from a grocery store along with its price. And then a question that students have to answer either Ja, jeg har nok penger (Yes, I have enough money) or Nei, jeg har ikke nok penger (No, I don’t have enough money). Because this exercise falls in the food chapter, that would be a good repeat of vocabulary as well. So, there you have it. There’s nothing more authentic than re-writing and editing curriculum!

7. Life-long learning

Thankfully, there are many students whose interests and ambitions don’t end when the final for the course is given. That’s one of the great things about teaching Norwegian — we have some very motivated learners. These learners often look for tools and resources to use once the course is complete or to supplement their curiosities during the course. One of the most frequently-used resources for language learning is a dictionary. The reality is that there are few online options for NOR-ENG or ENG-NOR dictionaries, and students don’t always have the skills to use them in the correct way. But, these skills are essential as Bilash, Gregoret & Loewen remind us that “dictionaries are the instruments of lifelong learning; it is to them that we turn to revive our second language skills and to enhance our native vocabulary” (1999, 4).

Ex. 10: Dictionary exercise

To develop students’ dictionary use skills, I created an exercise (Example 10) which guides students through how to use the online dictionaries. To do this, I used a program called “ScreenFlow” to record the movements of my cursor while narrating what I’m doing and why I’m doing it. And, the helpful IT folks also let me use their recording studio to do this so the recording would be professional quality. I hope to add more of these in the future, but they take considerable time to create. This example was a 19 minute recording which took maybe 5-6 hours to create between writing the script, recording it, editing it and then programming an exercise to accompany it into the portal. If you consider that there are approx. 25 exercises per chapter and there are 30 chapters, this was a significant amount of time used on one exercise. That said, the technology used wasn’t difficult at all, just time consuming!

8. Raising metalinguistic awareness

We have included a number of activities aimed at increasing metalinguistic awareness in the portal. Metalinguistic awareness is defined by Roth, Speece, Cooper, & de la Pazas “the ability to objectify language and dissect it as an arbitrary linguistic code independent of meaning” (1996, 258). Research findings (Sorace, 1985; Alderson, Clapham & Steel, D., 1996) have suggested that raising metalinguistic awareness in foreign language teaching is essential and results in more accurate production of grammatical structures. The findings of my dissertation (Lie, 2009) resembled these findings; language learning involved more than practicing the FL; reflecting on grammatical forms or other linguistic concepts in the students’ native language was found to be an integral part of language development.

In fact the dictionary example above could be considered an example of this as it is examining noun forms. Another example is shown below in example 11; here students consider two examples of how British & American English and Norwegian are related.

9. Reducing Anxiety (Foreign Language)

Research has shown that stress and anxiety impede FL production and achievement (Horwitz, Horwitz & Cope, 1986; Horwitz & Young, 1991; Crookall & Oxford, 1991; Krashen, 1985). What is it that stresses students and makes some students anxious with using a portal such as ours? Well, that varies; for some it is language, for others it is technology, for others it’s both. Krashen’s (1985) affective filter hypothesis suggests that acquisition can only happen if conditions are optimal (such as the acquirer being motivated, having self-confidence and a good self-image, and a low anxiety level). With all this in mind, one of our very first brainstorming sessions was ways in which to help learners feel at ease, knowing that some would be more anxious with the language and others with the technology.

One of the ways in which anxious foreign language learners can gain confidence is by simply using and practicing the language. The overwhelming majority of students who come to my office to talk over undesirable grades have completely underestimated the time it takes to master a foreign language. Students are bombarded with false claims in the media of the time it takes to become proficient language users, or if not proficient, to ace a chapter test. The reality is we just do not have enough class time, students have to spend considerable time practicing on their own.

We concluded that the portal could and should provide more facilitated practice. In addition to the exercises we modified in order to be used in an online setting (approx. 1/2), we created an average of 5 new exercises for each chapter (=ca. 150 new exercises). To get us started, the CURI students went through the results of exercises taken by previous students on the St. Olaf Moodle course to get ideas as to what students needed more practice with; their task was to specifically look for trends.

Take an example: several times they found that around 50% of students scored quite low on one specific exercise, that told us students need more practice on the given grammar point or that the exercise was confusing and the directions or some other part needed to be re-written. Sometimes we added an easier exercise to scaffold to the more difficult, pre-existing exercise. Example 12 is such an exercise; we felt that students needed more practice with time expressions, something a bit easier, something with set answers before students used this grammar point in an open-ended assignment. Thus, by completing this exercise, students will be better prepared for the written assignment.

It wasn’t just providing more grammar exercises though, other types of exercises are essential as well. One of the things I really felt strongly about was that we needed additional facilitated listening exercises. We already had many discrete listening exercises in the print version of the workbook (many cloze exercises, for example). But, one area that I have felt lacking in our curriculum is enough exercises geared at developing global listening skills, e.i. developing “getting the gist” skills. To explain how and why we did this, I need to rewind back to 2001…

The very first project Nancy and I collaborated on, even before co-authoring Sett i gang textbooks, was that we filmed somewhere around 2,000 clips of native speakers. Essentially, we prompted speakers with a question, had them first write out responses, and then filmed their responses. We filmed them speaking naturally, not reading their written responses. This was intentional because we wanted a more natural clip, having them write out their responses solely provided an opportunity for self reflection on the question. We also found that this method worked well because they were more ready to talk, we didn’t need so many takes.

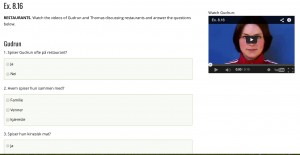

Take for example the topic of eating out at restaurants. We can give statistics in the textbook for how much less frequently Norwegians eat out or what types of restaurants Norwegians eat at, but there is also value in hearing/ seeing a Norwegian discuss their own habits. Prompted by questions such as “Do you eat out at restaurants? If so, how often and with whom?” we filmed natives & edited the video clisp and then created exercises to go with some of these video clips (a few hundred of them). Early piloters of the Sett i gang curriculum received a number of these video exercises on CD-ROMs (5 CD-ROMS per student which Nancy individually burned for about 500+ students two years in a row= craptastic unpaid side job), but it was never anything we used in the final version of the first edition.

We had great intentions with this video project but soon after we embarked on this daunting venture, we realized that supplementing video clips to the curriculum we were using wouldn’t suffice, we needed to write an entirely new curriculum. So, this valuable resource was never really utilized. Now that it isn’t nearly as expensive or time-consuming to disseminate these video (thanks to YouTube), we’ve decided to use a number of the videos in the second edition. Example 13 shows an example of Gudrun, a native speaker discussing the “eating out” question discussed above. What you don’t see pictured is below the exercise of Gudrun is a very similar set of questions with another native speaker, Thomas, with different answers as he has different habits. The focus of the exercise is to understand the main ideas. Gudrun, like many of the speakers we chose, speaks a dialect, hers being trøndersk. So, this is a perfect opportunity for students to understand that they don’t need to understand every word Gudrun says in order to get the main idea of what she is saying, it gets them to focus on the main message. It’s a lesson in reality really because most Norwegians can’t claim 100% trøndersk comprehension.

We have differentiated the video exercises from the audio exercises by including a variety of dialects in the videos, where the emphasis is on global listening skills. The majority of the questions within the audio exercises focus on more discrete language use, so these use only speakers from Oslo or østlandet. We’ve also recorded a number of new audio clips, both adding to and improving upon some of the existing recordings.

On a related note, in the first edition, students download all the audio from our website, including the clips for the corresponding workbook exercises. In the portal, the clips needed for each exercise are embedded within the workbook exercise. We believe this helps students too, the less time they spend searching for something the better! In the portal, they have what they need on one screen, this will especially benefit those who feel anxious about the technology.

10. Reducing Anxiety (Technology)

This brings us to how students use the technology. Some of our students have never experienced learning a language with technology before. It feels like there are fewer of these students each year, especially at the university level. But, Sett i gang is also used at a number of programs with older learners, where comfort with technology varies greatly.

Ex. 14: Tutorials

Having used a considerable amount of & various forms of technology in my language courses for over the past 15+ years, I believe that it is important to separate the learning of technology from the learning of the language in the very beginning of a course. Students need an opportunity to learn the technology first before they use it to produce language. Additionally, because I don’t have the time to be tech support for the hundreds of students who will eventually use the portal, it was important for us to think through how students (and the instructors) would learn the technology.

One of the things the CURI students created was video tutorials for each of the pieces of technology used in the portal. These are step-by-step guides on how to use the technology, in English. Pictured in example 14 is a tutorial which welcomes students, gives an overview of the pieces of the portal and instructions for how to get started. There are also tutorials for each technological tool (flashcards, quizzes, audio) as well.

The idea being that before students use these tools, they can learn how to use them in English. That said, I don’t believe all students will use these tutorials; they are accessible for those who feel the need to be walked through the technology and hopefully will feel less anxious when they move on to a foreign language task.

A second example of how we have tried to get students comfortable with the technology first is by scaffolding the language used in the menus. The menus used to access the various parts of the portal are in English for the first 6 chapters of the book. Once they’ve completed chapter 6, which is a chapter on language learning and includes lots of vocabulary for language learning, we believe the students are ready for another challenge- that they access the portal with a Norwegian menu, as seen in example 15. Here, for example, the words kapittel replaces chapter and nettressurser replaces web resources.

As I’m sure you’ve realized, we had to think through a lot of CRAP this summer. Much of what we developed stemmed from my previous research, but some of it also was learned during the summer at the IT summer institute sponsored by The Digital Humanities on the Hill. Ben Gottfried (St. Olaf’s Multimedia Instructional Technologist) helped us piece together things that I had thought about before but never really knew enough about or how they fit together. Ben used the acronym CRAP to discuss Contrast, Repetition, Alignment and Proximity. These were all essential elements in designing a layout that would motivate and encourage learners. The implementation of this CRAP began with lengthy discussions the first weeks before we started to create content. Examples of some of the things we had to figure out was a color scheme: what was always going to be in color 1, what was always going to be in color 2, and what font(s) would we use, would they match the book or be different? If we use an accordion menu in one place, should we also use it in another? Should students scroll more or have to go through several sub-menus to get to an exercise? How would the layout work on a tablet or iPad? Would it have the same alignment?

We had so much fun learning about CRAP, it was a bash! I half-heartedly apologize to the Norwegian speakers reading this post for that horrible pun. To those of you who didn’t get it, time to start learning Norwegian! I know a great curriculum…

References:

Alderson, J., Clapham, C. and Steel, D. (1996). Metalinguistic knowledge, language aptitude and language proficiency. Centre For Language In Language Education. Working Papers Series 26.

Ausubel, D. P. (1968). Educational psychology: A cognitive view. New York: Holt, Rinehart, & Winston.

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84, 191-215.

Berardo, S. A. (2006). The use of authentic materials in the teaching of reading. The reading

matrix 6(2), 60-69.

Bilash, O., William, S., Gregoret, C., & Loewen, B. (1999). Using Dictionaries in Second-Language Classrooms. Mosaic 6.2(1999), 3-9.

Brown, K. (1996). The role of internal and external factors in the discontinuation of off-campus students. Distance Education, 17(1), 44-71.

Chen, B. (2014). Advance Organizer. In K. Thompson and B. Chen (Eds.), Teaching Online Pedagogical Repository. Orlando, FL: University of Central Florida Center for Distributed Learning. Retrieved November 10, 2014 from https://topr.online.ucf.edu/index.php?title=Advance_Organizer&oldid=358

Chen, B., & Hirumi, A. (2009). Effects of advance organizers on learning for differentiated learners in a fully Web-based course. International Journal of Instructional Technology & Distance Learning. Retrieved from http://itdl.org/Journal/Jun_09/article01.htm

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. New York: Harper and Row.

Egbert, Joy.(2003). A Study of Flow Theory in the Foreign Language Classroom. The Modern Language Journal 87.4, 499-518.

Harmer, J. (1991). The practice of English language teaching. London: Longman.

Herrington, J., Reeves, T. Oliver, R., & Woo, Y. (2004). Designing authentic activities in web-based courses. Journal of Computing and Higher Education, 16(1), 3-29.

Kearsley, G. (1999). Explorations in learning & instruction: The theory into practice database. Retrieved September 5, 2006, from: http://tip.psychology.org/theories.html

Krashen, S. (1985). The input hypothesis. London: Longman.

Lee, W. (1995). Authenticity revisited: Text authenticity and learner authenticity. ELT Journal 49(4), 323–328.

Lie, K. (2009). Virtual communication: An investigation of foreign language interaction in a Distance Education course in Norwegian. Dissertation Abstracts International, 69(9-A), 3484.

National Standards for Foreign Language Education Project. (1999). Standards for

foreign language learning in the 21st century. Lawrence, KS: Allen Press, Inc.

Northrup, P. (2002). Online learners’ preferences for interaction. Quarterly Review of Distance Education, 32, 219-226.

Roth, F., Speece, D., Cooper, D., & De La Paz, S. (1996). Unresolved mysteries:

How do metalinguistic and narrative skills connect with early reading? The Journal of Special Education, 30, 257-277.

Sorace, A. (1985). Metalinguistic knowledge and use of the language in acquisition-poor environments. Applied Linguistics, 6, 239–254.